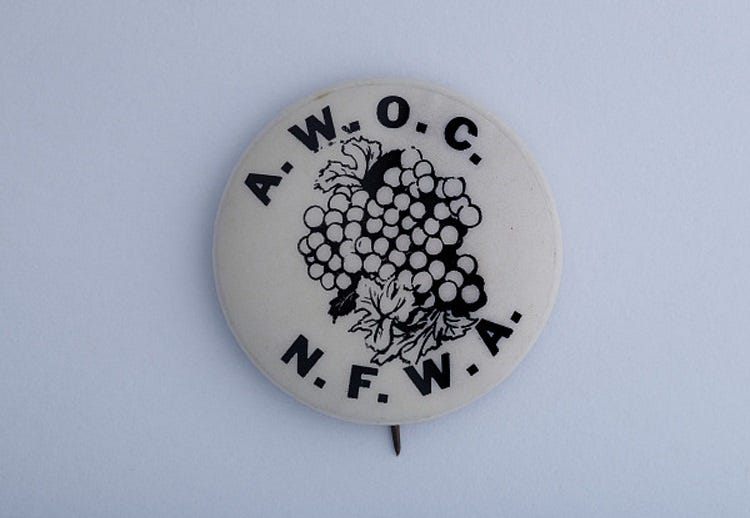

On February 23, 1959, the AFL-CIO Executive Council, meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico, passed a resolution to create the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), an early attempt to organize the farmworkers at the bottom of the American labor force.

While Americans idealized agricultural work from the Jeffersonian beginnings of the nation, underlying the agrarian myth was very hard work. For Jefferson himself, that work was done by enslaved black labor. The family farm was a real thing in America of course, and was the fundamental basis of free labor ideology that fed northern beliefs about capitalism. At base, it was why northerners opposed the expansion of slavery. After all, if slavery was the future of the nation, where was the room for the independent white farmer?

But farmers were as enmeshed in rapacious capitalism as anyone else and they really started feeling that in the Gilded Age, leading to the Farmers’ Alliance and the Populists. In the arid and semi-arid American West, family farms definitely existed —the Japanese were well known and resented for taking land whites thought were unproductive and turning them into really productive farms — but big corporate agriculture became dominant in the early twentieth century, especially in California.

Those big farmers relied on cheap, pliable labor and would do anything to get it, including lying to workers about jobs to recruit too many, then reduce wages. When workers organized around the abuses, the big farms would send police to crush them, as happened in what became the 1913 Wheatland Riot. There were occasional attempts to unite the different races working in the fields, such as the Japanese-Mexican Labor Association, but they were hard to maintain against the violence, not to mention hostility from the white labor movement.

By the Great Depression, there were early attempts to organize farmworkers, who were by then increasingly Mexican. The United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA) formed in 1937 as a multiracial union to organize the food workers of the Southwest, and did some pretty amazing work before being redbaited out of existence. The arrival of a lot of conservative white migrants from the South fleeing their eviction off tenant farms due to the Agricultural Adjustment Act definitely did not help UCAPAWA’s organizing efforts. Also, despite Steinbeck, the Dust Bowl area, lightly populated even then, led to relatively few migrants. Even in the novel, the Joads themselves were clearly from central or eastern Oklahoma. (This fact, however, will not stop high school teachers from assigning essays on the symbolism of the turtle in Chapter 3.)

During World War II, the government attempted to “solve” the agricultural worker problem through the incredibly exploitative Bracero program, which brought guest workers, mostly from Mexico, to the United States to work on the farms. This was a horrible labor system that gave workers no rights or recourse to the massive racism, wage theft, unsafe working conditions, and unsanitary living conditions they faced. By 1959, it was clear the Bracero program was on its last legs, and the AFL-CIO decided to act and move toward some organizing campaigns in the fields.

AWOC had its first base among the aging Filipino farmworkers on the West Coast who had been laboring in the fields for several decades, before 1934’s Tydings-McDuffie Act ended Filipino migration and set the Philippines on the course of independence. That law was largely a reaction to the fact that Filipino men and white women were having sex, and Americans decided that colonialism was not worth the price of interracial sex.

The union’s most important leader was Larry Itliong, who sought to end the Bracero Program and organize agricultural workers into unions. Itilong was not initially running AWOC, but the long-time Filipino organizer was the clear leader of this movement on the ground: He had lost three fingers in an Alaskan salmon cannery, led the 1948 asparagus strike in California, served as shop steward of International Longshore and Warehouse Union Local 37 in Seattle, and founded the Filipino Farm Labor Union in 1956.

AWOC’s first big action was the 1961 lettuce workers strike, in which they went after both the growers and the Braceros, using the clause in the Bracero Program that they couldn’t serve as strikebreakers to specifically target farms where they worked. AFL-CIO President George Meany didn’t like the bad publicity this caused, and he tried to shut down AWOC in the aftermath, but it struggled along for a few more years. By 1965, Itliong was the head of AWOC.

The biggest challenge AWOC faced was from Mexican farmworkers who were willing to break Filipino farm workers’ strikes. But this changed in 1965 with the Delano strike, where Cesar Chavez first came to the attention of the nation. Chavez’s National Farm Workers Association, founded in 1962, joined AWOC on the picket lines. Soon, the two organizations merged into the United Farm Workers. Itliong was rightfully concerned that the needs of the aging Filipino workers would be subsumed under the majority Mexican UFW membership. In fact, that did happen, but it was perhaps inevitable, since AWOC as a strictly Filipino organization lacked staying power due to demographics, if nothing else. Itliong finally broke from Chavez in 1971 and resigned from the union’s executive board. The struggle for farmworkers rights continued and continues today.

Once again, the nation now seems determined to hurt immigrants. Doing so is going to decimate the agricultural labor force. The people who will suffer the most are going to be the deported immigrants. The second group of people who will suffer is the American consumers. But hey, what is a $5 apple or $10 bin of lettuce in exchange for making me feel so righteous and white???

Craig Scharlin and Lilia V. Villanueva, Philip Vera Cruz: A Personal History of Filipino Immigrants and the Farmworkers Movement

Cletus Daniel, Bitter Harvest: A History of California Farmworkers, 1870-1941

Don Mitchell, They Saved the Crops: Labor, Landscape, and the Struggle over Industrial Farming in Bracero-Era California

Frank Bardacke, Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers

Matt Garcia, From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement

Don Mitchell, The Lie of the Land: Migrant Workers and the California Landscape

Frank Barajas, Curious Unions: Mexican American Workers and Resistance in Oxnard, California, 1898-1961

Mireya Loza, Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual, and Political Freedom

Andrew Hazelton, Labor’s Outcasts: Migrant Farmworkers & Unions in North America, 1934-1966