[ad_1]

For years, Catholic Charities has been fighting for its First Amendment right to screw over its employees by not paying into the state’s unemployment insurance system. Last Thursday, the Wisconsin supreme court ruled 4-3 that four affiliates of the Superior Catholic Diocese are not exempt from Wisconsin’s unemployment law and have to pay into the system, like (almost) everyone else.

Essentially, the court reasoned that the work Catholic Charities was doing was “charitable and secular,” rather than “operated primarily for religious purposes.”

That may sound weird, but I’m not sure the court is wrong … though I’m also not sure we’ve seen the end of this case. Let’s get to it.

The deal is that most employers have to pay into unemployment insurance. That’s what keeps the system running and allows people to receive unemployment when they’re fired or laid off.

What a lot of people don’t realize is that whether or not you can collect unemployment if you’re fired or laid off depends on who your former employer is.

The specifics vary by state. In general, churches themselves are exempt from paying into unemployment, but not all religious-based nonprofits are. Wisconsin law says whether or not organizations have to pay into the system depends on whether or not the organization is “operated primarily for religious purposes and operated, supervised, controlled, or principally supported by a church or convention or association of churches.” This mirrors the language in the Federal Unemployment Tax Act and is used by a lot of states.

A bunch of back-and-forth eventually led to this decision. Catholic Charities has been paying into unemployment since 1972, when it filed a form with the state describing its purposes as “charitable,” “educational,” and “rehabilitative,” not “religious.” In 2015, after another Catholic Charities sub-entity, not involved in this case, sued the state, a lower court found that another Catholic Charities organization was “operated primarily for religious purposes” and therefore exempted from the state’s unemployment laws. Since then, more Catholic Charities affiliates in the state have been trying to get the same exemption.

There are some basic facts about Catholic Charities and the Wisconsin organizations involved in this case that help lay the groundwork for the court’s decision.

Catholic Charities describes its mission as “to provide service to people in need, to advocate for justice in social structures and to call the entire church and other people of good will to do the same.” It also says that “no distinctions are made by race, sex, or religion in reference to clients served, staff employed and board members appointed.”

As for the services it provides, Catholic Charities operates 63 programs “to those facing the challenges of aging, the distress of a disability, the concerns of children with special needs, the stresses of families living in poverty and those in need of disaster relief.”

Catholic Charities Bureau acts as kind of an umbrella organization that helps manage and operate its other nonprofit organizations. Four Catholic Charities affiliates were involved in this case: Barron County Developmental Services, Black River Industries, Headwaters, and Diversified Services. These organizations provide services like job training, job coaching, and employment opportunities for people with disabilities, and there is no religious aspect to the services provided. All four receive most of their funding from government contracts, and none are funded by the local Diocese.

Let’s get into the decision.

First, the court had to decide how to figure out whether an organization’s primary purpose is religious. Catholic Charities says that these organizations are operated for religious purposes; shouldn’t that be the end of the analysis?

Well, if you let organizations self-identify, they have a monetary incentive to choose the one where you don’t have to pay into unemployment. As the court noted,

Sole reliance on self-professed motivation would essentially render an organization’s mere assertion of a religious motive dispositive. […] Although the motivations of an organization certainly figure into the analysis, allowing self-definition to drive the exemption would open the exemption to a broad spectrum of organizations based entirely on a single assertion of a religious motivation.

The court also looked at the actual text at issue: “operated primarily for religious purposes.” Because the statute talks about both “purposes” and how an organization is “operated,” it reasoned, you have to look at both the motivation behind an organization and what it actually does.

In the end, the court found that the organizations’ activities in this case were “primarily charitable and secular.” The services they provide “can be provided by organizations of either religious or secular motivations, and the services provided would not differ in any sense.” As evidence, the court noted that one of the organizations in question, Barron County Developmental Services, had not had any religious affiliation until it was absorbed by Catholic Charities in 2014 — and its services didn’t change when the two became affiliated.

The court also noted that federal law supports its decision here. Wisconsin’s religious exemption uses the same language as its federal analogue — and that language was added specifically to conform with federal law. A House Ways and Means report on the federal unemployment law reported that:

Thus, the services of the janitor of a church would be excluded, but services of a janitor for a separately incorporated college, although it may be church related, would be covered. A college devoted primarily to preparing students for the ministry would be exempt, as would a novitiate or a house of study training candidates to become members of religious orders. On the other hand, a church related (separately incorporated) charitable organization (such as, for example, an orphanage or a home for the aged) would not be considered under this paragraph to be operated primarily for religious purposes.

So, it does seem to me that the court got this one right.

Catholic Charities didn’t only argue that it should qualify for the unemployment law exemption; it also claimed that the court’s analysis was, itself, a violation of the First Amendment. According to Catholic Charities, an analysis of its operations “requires Wisconsin courts (and government officials) to conduct an intrusive inquiry into the operations of religious organizations that seek the religious purposes exemption.”

This, of course, ignores the fact that the First Amendment has never meant the government can’t analyze whether organizations with a religious hook qualify for things like tax exemptions. Like the court noted, “[t]he Establishment Clause does not treat religion as a third rail that courts cannot touch. Rather, it ensures that the inevitable ‘degree of involvement’ in such a determination does not cross into an evaluation of religious dogma.”

The court wasn’t deciding whether the organizations’ “activities are consistent or inconsistent with Catholic doctrine” or “whether they are ‘Catholic’ enough to qualify for the exemption”; it was deciding whether, based on their operations, they qualify for a tax exemption. Just like it would do with any other business.

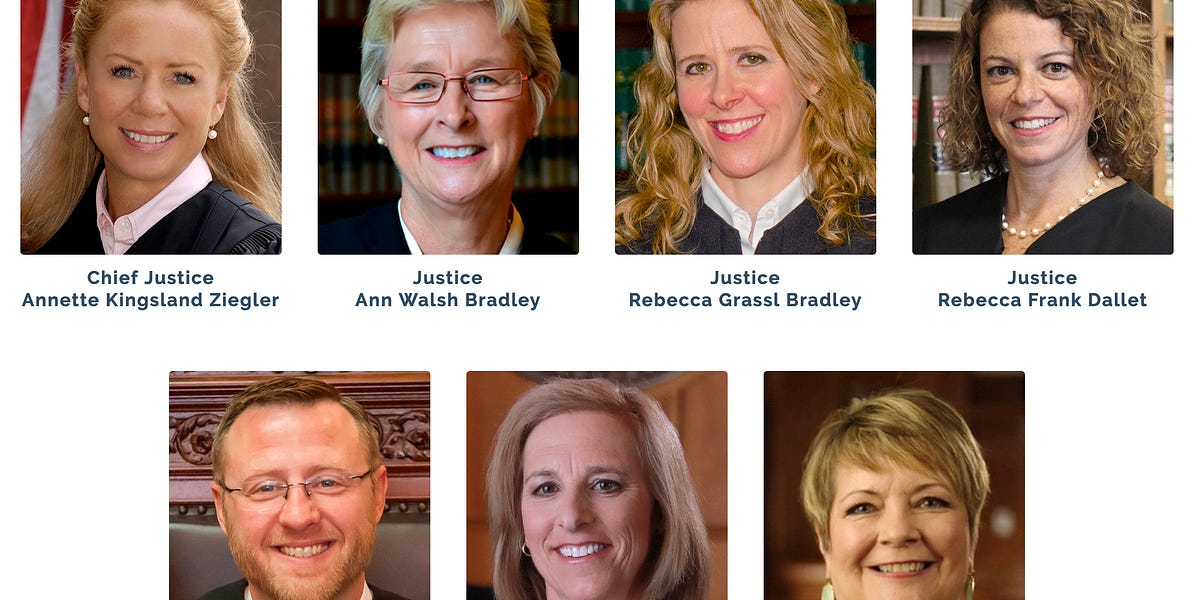

We don’t need to get into the weeds on the dissents, but I would be remiss if I didn’t point out the dissent penned by Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley (not to be confused with Justice Ann Walsh Bradley, because yes, the Wisconsin supreme court has two Justice Bradleys). Justice Rebecca Bradley, who has apparently been taking some community college creative writing classes since Justice Janet Protasiewicz was sworn in last August, began her dramatic dissent about the importance of the separation of church and state by … quoting the Bible. (I wish I were kidding.)

Render therefore unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s.

Well, if the BIBLE says so, I don’t know how the court could possibly disagree! (Also, wasn’t that particular quote actually about how people should, in fact, pay their taxes?)

My hottest take, here, is that we need to change the law.

I absolutely think that these organizations should have to pay into unemployment, and I don’t think this decision is wrong … but I’m not sure it’s a great idea for courts to be in the business of deciding what counts as “operating for religious purposes.” I’m also afraid this could result in organizations doing things like forcing people to pray to baby Jesus to receive their services, like Salvation Army does. From a policy — and human — standpoint, that’s a morally reprehensible practice that should not be encouraged.

That said, allowing businesses to decide for themselves what tax breaks they qualify for isn’t exactly a brilliant idea, either — as shown by this case! The only reason we’re talking about this is because Catholic Charities is fighting tooth and nail for its right to screw over the employees it lays off. You know, just like Jesus would have done.

Also, Catholic Charities has already said it plans to take this case to the US Supreme Court, and I’m worried about what will happen if SCOTUS steps in. Not because I’m particularly invested in what happens with these four particular entities, but because this could lead to some more judicial fuckery from the Roberts Court.

This case gives SCOTUS the opportunity to both give a present to religious organizations AND throw a wrench in our unemployment insurance system — two things they would probably really enjoy. As we noted above, the Wisconsin law at issue uses the same language as federal law and a lot of other states. And while there is long-standing precedent upholding this kind of analysis … well, we all know how this particular Court feels about long-standing precedent (she writes from Wisconsin, which is currently governed by a pre-Civil War abortion law thanks to Dobbs).

There is a simply policy fix, here (at least until SCOTUS makes Christianity our official state religion): STOP EXEMPTING RELIGIOUS ORGANIZATIONS FROM LAWS THAT APPLY TO EVERYONE ELSE.

If you’re a business that would otherwise have to pay into unemployment insurance, you shouldn’t be able to get out of it by forcing people to pray. That’s just absurd.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link

![Chloe Cherry’s Gory New Slasher Revives ’80s Horror in New ‘Blood Barn’ Trailer [Exclusive] Chloe Cherry’s Gory New Slasher Revives ’80s Horror in New ‘Blood Barn’ Trailer [Exclusive]](https://static0.colliderimages.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/blood-barn-1.jpg?w=1200&h=675&fit=crop)

![‘Stranger Things’ Star Reveals “There Wasn’t a Lot of Oversight” When Filming This Iconic Sci-Fi Crime Drama [Exclusive] ‘Stranger Things’ Star Reveals “There Wasn’t a Lot of Oversight” When Filming This Iconic Sci-Fi Crime Drama [Exclusive]](https://static0.colliderimages.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/sharedimages/2026/01/0392347_poster_w780.jpg?q=70&fit=contain&w=480&dpr=1)