A new report from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) finds that student test scores in fourth- and eighth-grade math and reading are down nationwide following the disruption that the COVID-19 pandemic caused to education. As Yr Wonkette’s Stephen Robinson noted yesterday, the news has prompted some very predictable stupid from rightwing politicians, who want to accuse Joe Biden of traveling back in time to March 2020 and closing all the schools, although a lot of people seem to recall him taking office in January of 2021 and accelerating the distribution of the vaccines, which made reopening schools much safer. What we’re saying here is that we may never actually know when exactly the pandemic became Barack Obama’s fault.

As Stephen pointed out, Biden actually made reopening schools one of his top priorities, and included teachers and school staff among the high-priority frontline workers targeted to be vaccinated first during the vaccine rollout. Most schools were back to either in-person or hybrid learning by fall of the 2021-2022 school year, and it’s worth remembering that in many red states that fully reopened schools before the vaccines were available, there were often serious outbreaks that caused schools to close again. Republicans and pandemic deniers/downplayers — ah, but I repeat myself — are pushing a narrative that terrible Democrats forced all the schools to close forever, leading to catastrophic learning losses, but as education news site Chalkbeat discusses, the NAEP data are more complicated than that, and simply don’t support such broad claims when you look at state-by-state performance:

No state was completely spared from the pandemic’s academic wreckage. Every state in the country saw declines on at least one exam, and students in most states lost ground on multiple exams. Similarly, among 26 cities that participated in the exam, scores fell on at least one test everywhere.

As a fun trivia note, Chalkbeat notes that in schools run by the US Department of Defense, students actually did get higher scores on eighth-grade reading. This does not mean we need to turn all public schools over to the Pentagon, however.

The Chaos Hit Schools Everywhere

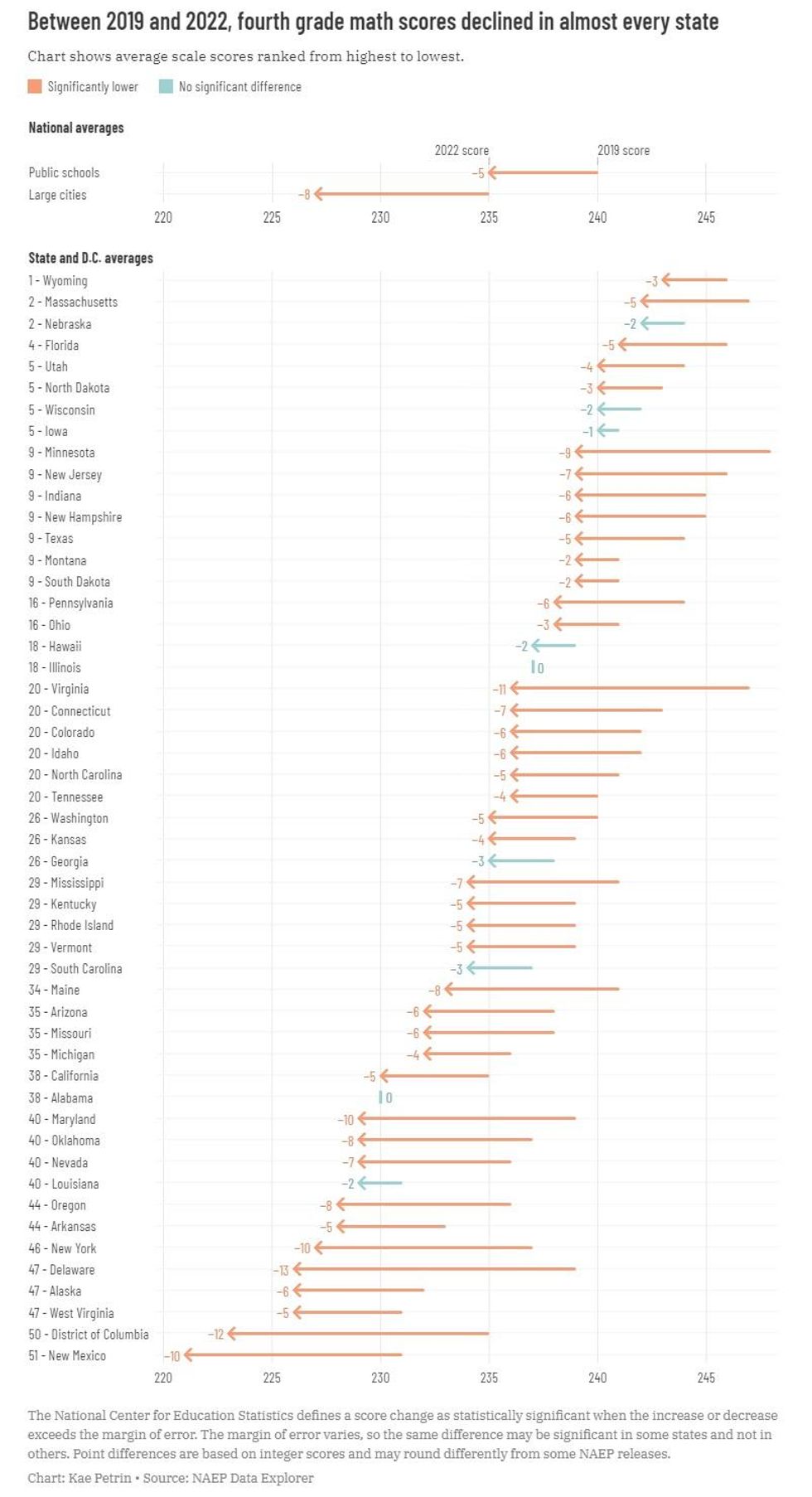

Digging into the data makes fairly clear that the disruption to education during the pandemic was everywhere, even in states that pushed to reopen schools before the vaccines were widely available. Chalkbeat put together this chart showing the average losses in fourth-grade math scores between 2019 and 2022, ranked from highest to lowest overall score by state.

Take a look at Texas and Florida, whose governors proudly rushed school reopenings in the spring of 2021and used coercive executive orders to try to prevent local officials from even mandating students wear face masks. Both saw five-point average declines in fourth-grade math. But so did California, where depending on district, in-person classes mostly didn’t resume until the 2021-2022 school year.

Chalkbeat also notes that if you look at all four tests, the evidence is “mixed”:

In fourth grade math, states where schools were fully open for longer tended to see smaller declines in scores. In eighth grade math and fourth grade reading there was also a relationship, but it was very modest. In eighth grade reading, there was no correlation at all.

On the whole, though, Chalkbeat warns that the NAEP data simply isn’t detailed enough to prove cause and effect, particularly since the state results “come with larger margins of error than the country as a whole, though, and many factors could affect score changes.” The piece also notes that “More granularresearch has shown that students who experienced more virtual learning tended to fall further behind.” And given the widely variable effects of the pandemic in different areas, even schools that were mostly open had to deal with staff shortages, teachers falling sick, and students facing huge disruptions at home.

It’s Hard To Learn When You Can Only Get Wifi In A Taco Bell Parking Lot

As everyone — OK, everyone who was paying attention — noticed in those first months of the pandemic, the switch to online learning was especially disastrous for kids who couldn’t easily get online. That drove a key part of the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which included $65 billion to build out high-speed broadband in rural and urban areas that have gone too long without it.

And as you’d expect, the NAEP data suggest that educators were right to fear that the pandemic would be especially hard on kids who were already behind — at least, as Chalkbeat explains, “in some but not all cases.”

For instance, in fourth grade math and reading, scores for the highest-performing students changed modestly, if at all. But the lowest-performing students saw particularly large drops. This continues a trend seen even before the pandemic.

Black and Hispanic students also experienced larger-than-average dips on fourth grade tests, widening already yawning test score gaps compared to white and Asian American students. Such disparities did not increase in eighth grade, though.

Golly, it sure sounds to us like one of the lessons here is that we needed to be improving elementary education in disadvantaged communities even before the pandemic, and that we need to focus on that even more now. That’s especially important to keep in mind when we’re talking about where resources need to go as we rebuild from the pandemic. The kids that need the most help aren’t the ones who were doing great before the pandemic (I’m not saying we should ignore them; they need help too), but the kids who have fallen behind the most deserve schools that can help them begin to catch up.

It’s going to be hard, especially with school boards being taken over by MAGA candidates who want to blow up public education altogether and divert public funds into private schools or for-profit charter schools that can skim off the high achievers and leave more challenged kids to rot.

‘Bottle Rockets At The Moon’: How Do We Fix This?

For starters, portents of doom are almost certainly overhyped. In an AP story that’s pretty informative overall, we were annoyed by the apocalyptic tone in this paragraph, which sounds exactly like a million other “SCHOOLS IN CRISIS” stories from long before the pandemic.

There are fears for the futures of students who don’t catch up. They run the risk of never learning to read, long a precursor for dropping out of school. They might never master simple algebra, putting science and tech fields out of reach. The pandemic decline in college attendance could continue to accelerate, crippling the U.S. economy.

I’m fairly certain I read nearly the same fretful stuff when I was still working on my BS in Education during the Reagan administration, back when America was “a nation at risk” because of our terrible schools, and we were on the verge of being left in the economic dustbin by Japan and Red China.

Yes, absolutely the pandemic has created serious challenges for schools that already desperately needed help before the pandemic. The challenge is especially difficult now that teachers, like everyone else, are simply exhausted. (I’m very sympathetic to the view someone shared on Twitter that the world could use a good two-year nap.) Academic Twitter is full of college instructors wondering what to do about students who’ve never cited a source or read a basic paper in science, and classes where nobody at all has done the reading.

So given that schools are already understaffed and everyone’s on edge, the AP’s casual suggestion that learning gaps might be addressed by “Saturday school or doubling up on math or reading during a regular school day” sounds downright nuts. The American Rescue Plan provided $190 billion in emergency funding for schools, which Chalkbeat notes is being used for a “variety of catch-up strategies”:

Chicago, New York City, and Memphis and many others have expanded summer schools. A number of Michigan districts have added more small group instruction. New York City added an after-school program specifically for students with disabilities. Chicago, Arkansas, New Mexico, and elsewhere have hired hundreds of tutors. Houston created a peer tutoring program.

In Decatur, Illinois, the schools have hired additional reading specialists for each elementary school; they’re able to pull kids out of class for small group work. In some districts, year-round school may become an option. The additional efforts do seem to be paying off, if slowly.

But there are also hiccups in the education supply chain: Extra tutoring is terrific and generally gets results. But there are challenges, even when the funding is available.

Tutoring initiatives have often struggled to reach the “high dosage” threshold — multiple sessions a week of small group, in-person work during the school day — that researchers say is likely to work best. Staffing shortages have meant that schools can’t hire all the new people, including tutors, they expected. In some cases, attendance for optional programming has been less than officials hoped.

Why yes, more funding is needed, even as schools are still figuring out what will help. As Jason Kamras, school superintendent for Richmond, Virginia, told the AP, “We need something on the scale of the Marshall Plan for education” to help kids get back on track.

We’ll close, though, with a slightly different historical metaphor, this one from Harvard education prof Tom Kane, an expert in learning loss. He agrees that the effort to get students caught up has to recognize the scale of the challenge:

“What most school districts are doing now is the equivalent of shooting bottle rockets at the moon,” he said. “The things they’re trying are directionally correct, but nobody has actually added up the amount of thrust that is going to be needed.”

Funny, though: Not one of the education experts thinks that kids will start making headway again if only we’d ban books with tiny cartoon genitals, forbid teaching history accurately, or have big fights about which bathroom kids can use.

[NAEP report / Chalkbeat / AP]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by our well-read thoughtful readers. If you can, help us out with a monthly $5 or $10 donation. We can’t guarantee we’ll fix everything, but we can at least kick the ideas around together.