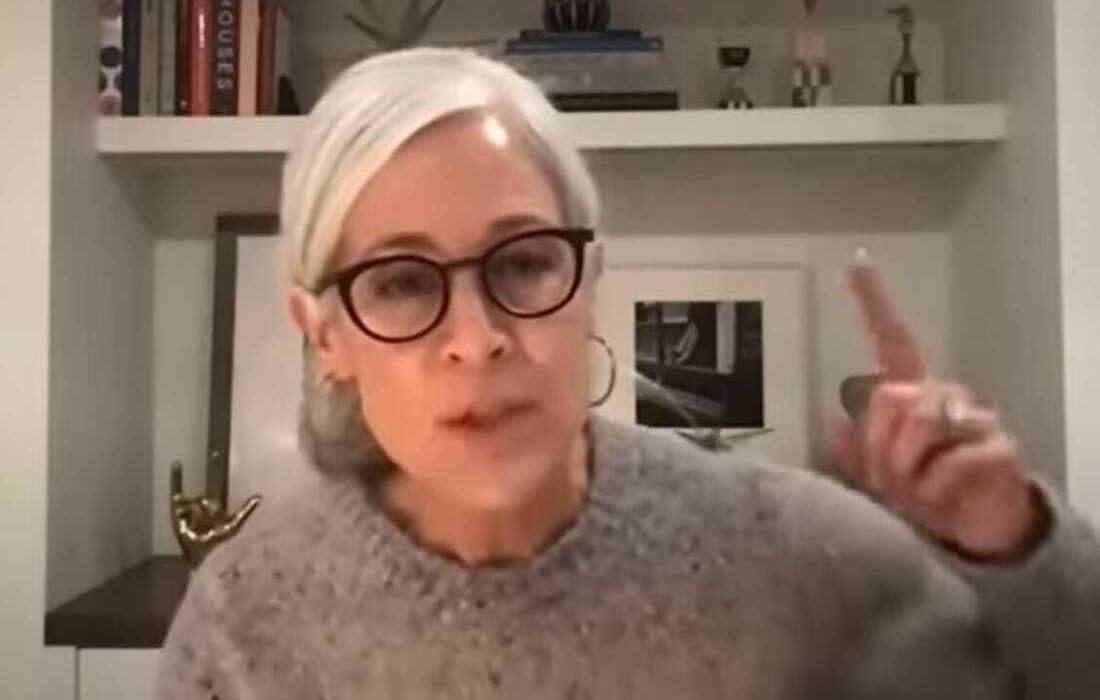

MillerKnoll CEO Andi Owen looked painfully out of touch when she told her discouraged employees to “leave Pity City” on a recently-leaked video call—but it didn’t need to be that way.

As a coach to CEOs, I know that no executive is perfect. Talk long enough, and eventually you’ll talk your way into trouble. That’s why corporate leaders need a blueprint to prevent gaffes and repair harm when it’s done.

Owen’s error was a classic case of CEO myopia. She assumed her employees saw the company as she did. They did not. They were discouraged that they may not receive any bonus this year, while their boss—who took home $5 million last year—told them to get over it and work harder. Her team needed empathy; she gave them a lecture.

• Know your stakeholders.

For executives, the best way to prevent trouble is to stay close to your stakeholders, in this case Owen’s employees. Ensure you have the pulse of your workplace, so you can anticipate employee concerns and test your response in small groups.

In Owen’s case, she showed a shocking lack of awareness of one of the most prevalent societal touchpoints of the moment: the discrepancy in wealth between highly-paid executives like herself and the people they employ.

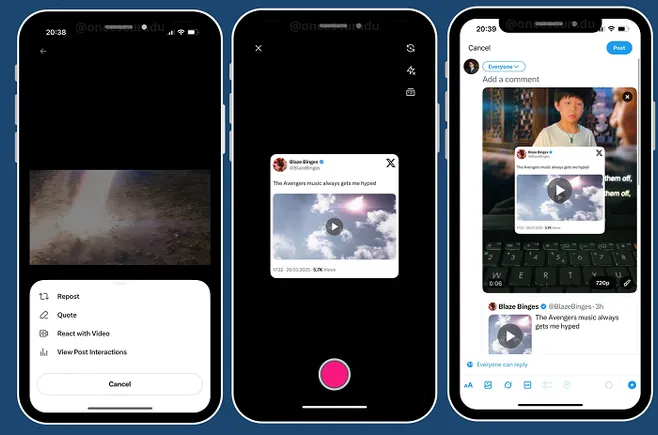

• Realize Zoom leaves you blind.

Another way CEOs can prevent similar disasters is to recognize the limits of remote communication in the age of Zoom.

If Owen had begun her tirade in an in-person town hall meeting five years ago, she probably would’ve seen the furrowed brows, heard the murmurs, and felt the uncomfortable shifting in seats that her comments sparked. But today, when most communication at large organizations takes place via video conference, you simply can’t perceive reactions as closely. This puts you at a major disadvantage in reading the room.

But let’s be realistic: Even when leaders prepare themselves properly, they’re still going to make mistakes. When that happens, what should they do?

• When you step on a landmine, call it out immediately.

We’ve all said something and quickly realized that it didn’t come out right. The moment you feel that way, take a beat and acknowledge it—before you move on. “That didn’t come out as I planned,” or “You know, I don’t like the way that sounded.”

If Owen had simply said, “Sorry, I don’t mean to lecture you. You’re raising a real concern, and I hear you,” then she might have stopped the damage before it went viral.

If you do it in the moment, you show authentic concern. If you wait until you’re already getting beaten up, it looks like you’re just trying to clean up a mess.

• Meet with the team and listen.

If you missed your snafu in the moment, it’s not too late. Your first act should be to convene a small group of employees who were on the call as quickly as possible. Make sure they comprise people from all over your organization. They should be workers on the front lines, not the C-suite.

This should be a listening session, with an emphasis on listening. Your job is not to argue or clarify. It’s to hear how people feel, demonstrate empathy, apologize, and pledge to improve.

This not only will help reduce the negative impact of what you’ve done, but it will also give you useful information about how your employees feel, so you can issue an effective response.

• Apologize on camera.

Next, it’s time to deliver a corrective message back to all employees. If you committed your error on camera, your apology needs to be on camera too. A written statement (Owen reportedly sent an apology by email) can feel cold and scripted.

Upset employees need to see your authentic concern, and an updated video clip can help counteract the bad one that’s circulated far and wide.

• Take action when words aren’t enough.

If the damage is severe, you’ll need to go even further. If you’ve insulted a group; started losing business; or face calls for boycotts, lawsuits, or regulatory scrutiny, you must go beyond words and take action.

That might mean taking a training course on the inciting issue. It might mean committing to spending more time with your on-the-ground employees by working from their offices or work locations.

It might mean volunteering to face some form of punishment, as United CEO Oscar Munoz did in 2017. After he mishandled the fallout from a passenger being forcibly removed from a United flight, Munoz asked that the board not name him chair, as his employment contract had called for.

While many pile on Andi Owen, I feel some sympathy. Her success over a 35-year career in fashion and office furniture was tarnished by an 80-second clip pulled out of a 75-minute meeting.

The same will inevitably happen to other leaders unless they know how to prevent such errors and earnestly repair whatever damage they do.