This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I’d heard of Lesléa Newman’s Heather Has Two Mommies long before I read it — after all, the book has been lauded and attacked, referenced and parodied, published and re-published. Heather Has Two Mommies was the first picture book to feature a same-sex family, and Newman is a successful lesbian author who has since penned dozens of children’s books, including many more on LGBTQ+ themes. Heather is such a well-known and groundbreaking book that its origin story has been many times before, so instead of repeating the words of others, I reached out to hear from Newman herself. I spoke to her at her favorite time of day, 11:11 a.m., a fabulously whimsical time to discuss children’s picture books. (Okay, it was 8:11 a.m. my time, less whimsical, but in my opinion, you set an alarm, drink a bunch of coffee, and don’t say no to someone else’s favorite time.)

Newman didn’t start out writing for children. Her early career centered around poetry. She attended the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics and was Allen Ginsberg’s apprentice. Okay, cool enough on its own but she also studied with poet Grace Paley, referring to the two of them as her literary parents. Newman was always open about being a lesbian in her writing and was already known for her published adult books, including Good Enough to Eat and A Letter to Harvey Milk.

In a 2011 interview with Ms. magazine about her writing pre-Heather, Newman said, “I wanted to read a book about Jewish lesbians, but I couldn’t find one, so I decided to write one.”

The Inspiration

And then, one day, an acquaintance stopped Newman on the street in Northampton, Massachusetts and said, “I don’t have a book that I can read my daughter about a family like ours. Someone should write one.”

The implication was clear and so, message received, Newman did. According to Publisher’s Weekly, it was her first time writing for kids. Newman tells me, “[The woman] planted the idea in my mind and then the reason I took that very seriously was because my experience of growing up as a Jew was reflected by her experience growing up with two lesbian moms. Meaning, I never saw myself reflected in children’s books.”

I related to that on many levels; after all, as a frizzy-haired, tomboyish Jewish girl who figured out I was queer as a teenager, I didn’t see myself in many books either. And I definitely didn’t see myself in books aimed at children, not until I was in my very late teens. This is how people part of a marginalized group are made to feel, as though they are alone in the world. So one of the most inspiring aspects of Heather is that it was totally community-supported. One woman felt a need for something and went to speak with a person she knew could help, and then that person went to another friend and another, and the book was worn of people’s collaborative efforts.

Reflecting on the picture book’s origin story as we talk, Newman recollects that the woman who’d approached her was also a Jewish lesbian. And after a beat, Newman adds, “Heather was really conceived by a community of Jewish lesbians.” In fact, the book was co-published with her friend, Tzivia Gover, another Jewish lesbian.

The Publication and Reception

Newman wrote the book and couldn’t get it published. Lesbian publishers claimed they knew nothing about the children’s book industry, and the children’s book industry was unfamiliar with the lesbian audience. But Newman was unwilling to give up because she knew that there was an audience pining for a book like this.

She explains about her drive, “And I thought of my grandmother, an immigrant from Ukraine who lived to be 99, she always said to me ‘Just because they say no to me, you think I’m finished?’” Newman had taken this philosophy as her own, and it inspired her to keep fighting to publish Heather.

Gover and Newman began fundraising in their own community; handwriting letters and sealing them into envelopes, promising that if people contributed $10, they’d get a copy in a year. Their notes also explained their money would be returned if the book wasn’t made. Careful records were kept, just in case, but they got the money. With black and white illustrations by Diana Souza, the first edition was published in December 1989.

Eventually, Sasha Alyson, the publisher of the picture book Daddy’s Roommate, came across the book. Alyson then reached out to Newman, and his publishing company bought out the book’s stock and took over printing future editions.

Publishers Weekly talked to Newman about the original book’s reception, writing, “At first, it was mostly gratitude from lesbian moms…Then there was a short mention in Newsweek, about how the face of the family is changing and here are some books that reflect that. Then the news traveled around the world and the controversy began. Throughout the ’90s there were many, many instances of people using the book for their own political agendas.” A New York Times article from 2020 noted that the American Library Association ranked it the 9th most banned book of the 1990s.

Alyson Publishing brought out a Special 20th Anniversary edition in 2010; the company folded that same year. The book went out of print for a time.

In the meanwhile, Newman was very prolific in writing books for kids and teens. Working with Candlewick Press, she published the devastatingly beautiful October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard, a multiple-award-winning book of poetry for teens. Candlewick wanted to know what was up with Heather and if Newman would be interested in collaborating on a new edition of it.

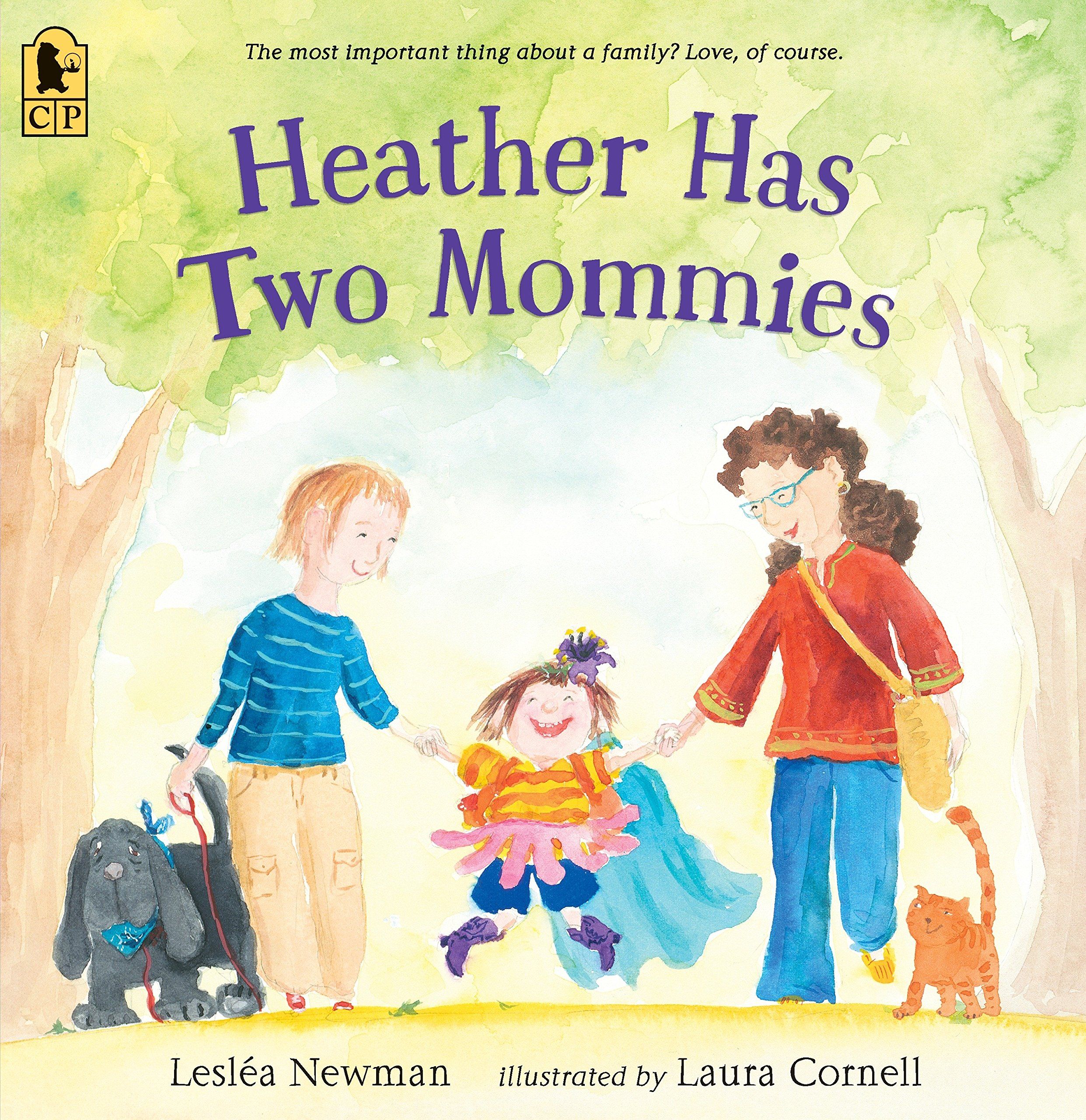

Candlewick suggested new art to brighten up the book and make it more modern and kid-friendly. Newman tells me that the large black and white illustrations in the original meant that some kids thought Heather was a coloring book.

The post-2015 editions feature art by illustrator Laura Cornell, who gave Heather cute purple cowboy boots and made one of her moms look like Newman herself. About the new art, Newman says, “She did a wonderful job, she showed diversity in Heather’s classroom…kids really respond to the liveliness and the energy of the art.” And the text was also changed a bit here and there, as Newman shortened it and made Heather more curious and less insecure.

So over 25 years after the book’s initial publication, it was given new life.

The Continuing Effect of Heather

Newman explains that Heather‘s life is still continuously challenged, unfortunately.

According to a 2015 report on CNN, Heather “has been challenged 42 times by legislators and parents wanting to remove it from local and school library shelves.” In our conversation, Newman points to the “well-funded, well-organized consorted effort to challenge-slash-ban many, many books including LGBTQ+ books for readers of all ages. Heather is still always on those lists…It’s back, an effort to show children a false picture of the world — meaning that really the only people in it and should be in it are white, cis-gender, heterosexual families…this does an incredible disservice and is harmful to everybody. It is important to not let that happen.”

Newman sees her book regularly back in the spotlight, and the mentions are not always positive. But she is positive about it, suggesting that if people want to support school libraries in carrying more diverse books, people should run for school boards, attend meetings, and get involved.

She adds, “It starts on the local level and expands from there.”

And so, despite the rampant attempts to ban and challenge diverse voices, there is hope. The book industry’s strides might be slow, but it’s encouraging. Not only are more LGBTQ+ books being published, but more of these stories are being written by members of the community. The Highlights Foundation is even sponsoring Newman and fellow author Rob Sanders to teach a writing workshop for up-and-coming authors and illustrators of LGBTQ+ children’s books. And increasingly, LGBTQ+-themed books are about more than just homophobia, acceptance, and struggle; they are about joyful moments too.

I asked Newman if she thinks the continuously blossoming diversity in picture books will continue. She is emphatic in her reply.

“I think it’s definitely going to last. More and more people are writing about LGBTQ+ families…more and more publishers are publishing these books — including mainstream publishers.” She and Heather may have been essential in beginning the story of queer children’s books, but many others have heeded the call since and so I’m excited to be able to believe her when she says, “It’s here to stay and we’re here to stay.”