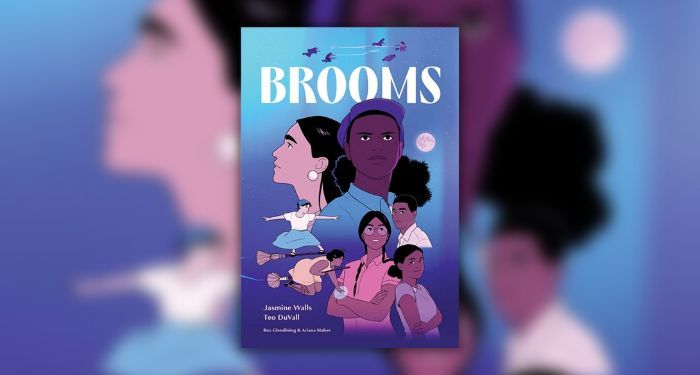

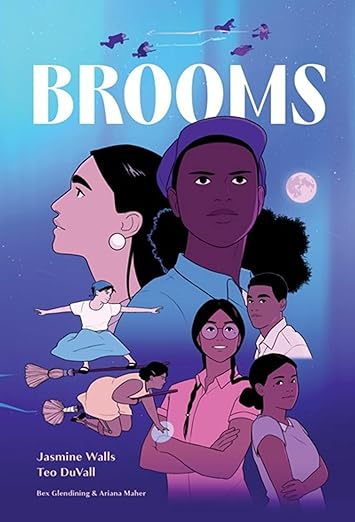

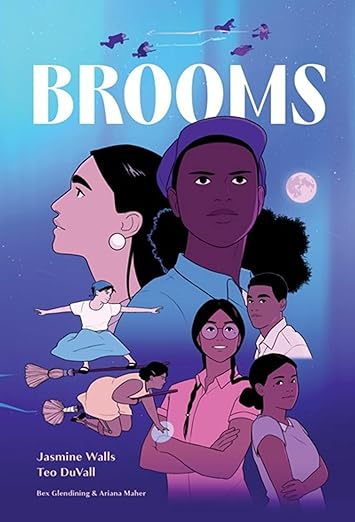

Brooms by Jasmine Walls and Teo DuVall

Set in an alternate 1930s Mississippi where magic is possible but restricted so only the most privileged may wield it, this book follows six young women determined to change their fates. Magic may technically be off-limit to many, but that doesn’t stop illegal broom racing from occurring beyond the reaches of the law, where the payout can be life-changing. Billie Mae and Loretta head a team, hoping to win enough so that they can move out west, where Black folks don’t have as many restrictions. Cheng-Kwan also wants to save money—for the inevitable moment when her parents find out she’s a girl and disown her. Luella doesn’t have magic, not since an act of rebellion ensured her powers were sealed for good, but she doesn’t want that to happen to her cousins Emma and Mattie, which is why she introduces them to Billie Mae in the hopes that they can train to become racers too. But in the world of racing, staying on your broom isn’t the biggest challenge to overcome.

I loved this premise so much—it’s a little bit A League of Their Own, but with magic, and it is very, very queer. All of the characters are people of color, and they’re all facing oppression and having to hide a piece of themselves away from the public eye, which is why racing is so important for them. It’s not just about their skills or the winnings. Racing is a community of people who are accepting and who support them, even if the competition can be fierce and the risk of exposure is constant. The creative team does such a great job balancing a large cast of characters, although the story of Mattie and Emma and the way Luella looks out for them is at the heart of this book. The art is expressive and colorful, and the racing scenes are incredibly vibrant and dynamic, making it easy to flip through the pages at breakneck speed. Even though this book is speculative, the historical setting rings true, and it doesn’t feel like such a stretch from real history. While there are no easy solutions to the serious systemic issues the girls face, this is not a depressing book. Walls and DuVall show that while oppression may be insidious, the collective power of community can prevail, even if there are no perfect endings tied in a neat bow. Ultimately, I was on the edge of my seat to see how this book would wrap up, and an epilogue of newspaper clippings and the illustrated ephemera gives readers a satisfying glimpse at life for the girls beyond the story’s conclusion.