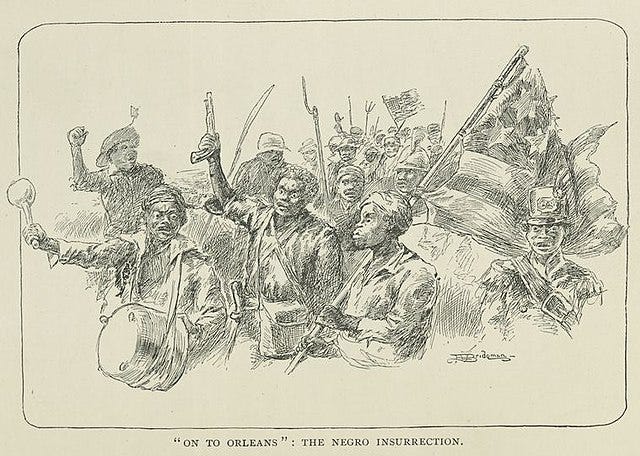

On January 8, 1811, the largest armed slave uprising in US history took place. The German Coast Uprising in Louisiana had up to 500 participants marching to New Orleans to attempt a Haitian Revolution in the United States. Only two white people died in this uprising, showing the extreme difficulty any slave revolt had in succeeding or even making a dent in the slave power within the United States. Yet for the significance of this event, it is almost completely unknown in popular American history, even compared to the rest of slavery history.

Louisiana developed a significantly different slave tradition than the rest of the United States. Whereas most early British North American slavery was in tobacco (and rice in South Carolina) and then cotton in the 19th century, Louisiana money was made in sugar. This made it much more like the Caribbean. There was a lot more money in sugar than the other crops. This meant wealthier planters and higher concentration of slaves. The German Coast of Louisiana, generally speaking St. Charles Parish and St. John Parish, had these concentrations. Some have estimated a 5:1 ratio although census records suggest a more even ratio. This matters because the larger the predominance of the slaves, the better the conditions were for organized rebellion, something whites knew and a fact that scared the bezeejus out of them, especially after the success of the Haitian Revolution.

From the perspective of the United States government and the nation’s white supremacist ideology, Louisiana was also a troubled place. While Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had close relationships with the French, after purchasing Louisiana, they did not believe the Creoles of Louisiana could govern themselves — they used the typical rhetoric of children needing to learn good government from the Americans that would be used against Native American tribes, the Philippines, and Latin America. Part of the discomfort was Louisiana’s different racial hierarchy, with a wealthy free Black community and common consensual interracial sex that led to skin tone rather than one drop rules dominating the racial hierarchy. Jefferson and Madison resisted granting Louisiana statehood, clearly guaranteed in the Louisiana Purchase agreement, until 1812. So when the slave revolt took place, it happened in a Louisiana undergoing rapid changes.

As for much about the history of slavery in this period, the specific details of even such a major event are pretty hazy. Planning for the revolt began on January 6, just after the end of the brutal sugar harvest. The leader seems to have been Charles Deslondes, with men named Quamana and Harry also playing major roles. Quamana and another slave named Kook were Asantes, evidently warriors, who had been imported from Africa around 1806. Deslondes summed up the fear of race mixing and the French system of slavery for American whites: a green-eyed man with greater education and access to the world than the average slave. He was the son of a white planter and Black slave and evidently was used as a slave driver.

The revolt began at the home of plantation owner Manuel André, about 36 miles north of New Orleans along Lake Ponchartrain in an area known as the German Coast because of a number of German planters in the area. André was struck with an axe and wounded and his son chopped to death. Deslondes brought the slaves from a plantation owned by widows where he was enslaved. Deslondes led the slaves into the plantation cellar for muskets and militia uniforms.

The precise numbers of slaves involved are unclear and estimates varied. The original revolt consisted of between 64 and 125 participants. As they marched toward New Orleans, they picked up more people along the way, leading to a final number of between 250 and 500. It’s thought that between 10 and 25 percent of slaves from the various plantations affected joined the rebellion, mostly single young men under 30. Armed with hand tools, knives, and a few guns, they marched for two days, covering twenty miles. The historical documentation is sketchy. But there is at least limited evidence that the slaves were aware of the Haitian Revolution and modeled theirs after it — a distinct possibility given that many Haitian planters had fled to Louisiana with their slaves during the Revolution. It also seems that some of the slaves had military experience in Ghana and Angola before their capture. We do know that the slaves marched in military formation.

Area whites panicked, fleeing to New Orleans, fearing a Haiti in their midst. And in fact, it does seem that Deslondes and the slaves wanted to conquer New Orleans. Later, after it was over, a slave named Jupiter was asked why he participated. He answered that he wanted to kill white people.

The response to the uprising was utterly brutal. Whites came at the slaves with maximum force. The US military combined with French planters to suppress the rebellion. The slaves came close to New Orleans before being turned around at Jacques Fournier’s plantation and crushed near modern-day Norco, Louisiana, on or very near the site of what is today the Waterford 3 Nuclear Power Plant. As they fled into the plantation backcountry and bayous, whites hunted them down. Another 44 were tried and executed. The total number of dead was around 95. What makes this response different than other slave rebellions is the brutality. Slave owners recognized the rebellion as a very real threat and wanted to be clear about the consequences. So they cut off the heads of the slaves, placed them on pikes, and lined the roads with them, in the most public and brutal suppression of slave agency in the nation’s history. The territorial legislature compensated the owners for the loss of their property by paying them $300 for each dead slave.

The federal-planter alliance to crush the rebellion helped smooth over the hard feelings about the federal treatment of the territory. Louisiana would become a state the next year. It also helped commit the federal government to the defense of slavery. Slowly Louisiana’s system of race and slavery would become more like the rest of the American South.

FURTHER READING:

Daniel Rasmussen’s American Uprising: The Untold Story of America’s Largest Slave Revolt

Thank you for being our friend and keeping us living forever! The button below will let you donate one time or monthly, in any amount of your choosing.

![Online Shopping Reached New Highs in 2024 [Infographic] Online Shopping Reached New Highs in 2024 [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/kCw9rTPPHoCqXkkL4Bt8p7eohxOuRs6iXsDK03Fxr_8/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9vbmxpbmVfc2hvcHBpbmdfc3VyZ2UyLnBuZw==.webp)

![What App Features Are People Willing to Pay For? [Infographic] What App Features Are People Willing to Pay For? [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/mHJQ6ffz2lGDUuF649StZz5xtI56ORDL5z-Cjs9ZUw8/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9hcHBzX3RoYXRfcGVvcGxlX3BheV9mb3JfMi5wbmc=.webp)

![Google Provides New Overview of Key Display Network Best Practices and Tips [Infographic] Google Provides New Overview of Key Display Network Best Practices and Tips [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/2ddZUevHZXiT7_iRCob1WNh0ZyGb8Dryr-h91-qV8Q0/g:ce/rs:fill:770:364:0/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL2dvb2dsZV9hZF9tYW5hZ2VyMi5wbmc.png)