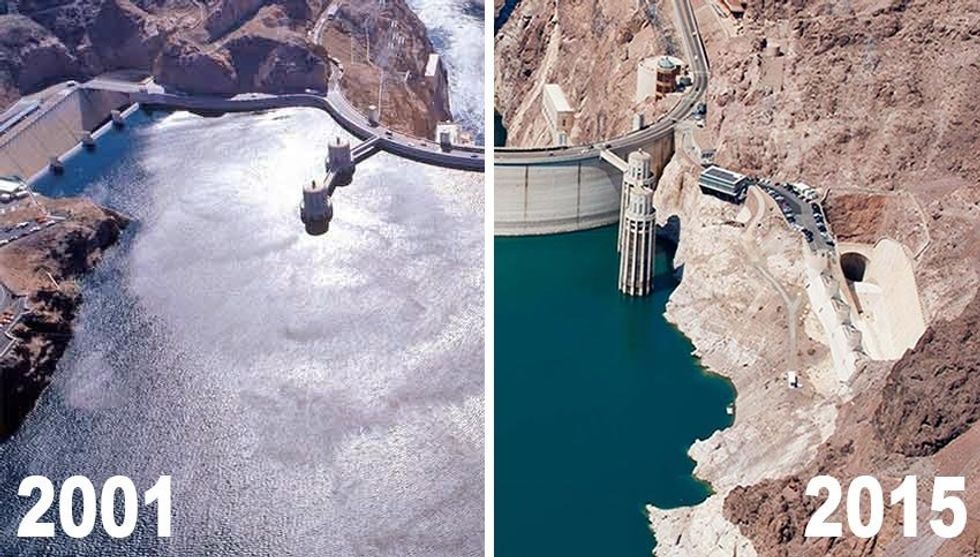

The Colorado River has been in pretty desperate shape for years, as drought and climate change have led to less water making its way from the river’s headwaters into the huge reservoirs of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which provide water and electric power to millions of people in the West. The low water levels in both lakes have left a “bathtub ring” of white minerals showing where the former high-water level was; in Lake Mead, that ring was about 140 feet above the current level of the lake, as this pair of photos from the National Park Service shows — and the level dropped to an even lower level last fall.

Until this year’s unusually snowy winter provided a brief respite — not an end to — the decades-long drought that’s prevailed in the Southwest, there were worries that both lakes might soon reach “dead pool” status,meaning they would be so low that water couldn’t pass through the dams and into the river below them, an ecological disaster that couldn’t even be relieved by a wisecracking superhero.

Fortunately for the roughly 40 million people in seven states who get their drinking water from the Colorado River, three of the states that use the most water from the river — Arizona, California, and Nevada — have reached an agreement, with negotiation help from the Biden administration, to conserve at least three million acre-feet of water — roughly 13 percent of the water legally allotted to them — by 2026. That’s a lot of water to be left in the river, as NBC News explains in one of those goofy try to visualize this crazy large amount with another crazy large amount comparisons. It’s “roughly the equivalent to the amount of water it would take to fill 6 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.”

An acre-foot of water is already an absurd measurement; it’s the amount of water needed to cover one acre of land (hey, visualize a football field!) to a depth of one foot. Multiply that by three million, and that’s even more football fields of water than the amount of tears cried by Buffalo Bills fans in the franchise’s history, but considerably less salty.

The agreement means the federal government won’t have to step in and impose limits on water allocations on the three states, which get their allotment of Colorado River water from Lake Mead, putting it under Bureau of Reclamation control (Reuters helpfully explains the other four states — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming — get their water directly from the river). But without the agreement, any federal divvying up of shrinking allotments would have led to lawsuits, so it’s a win-win for the feds and the states.

It’s also far better than anything that might transpire if Donald Trump were to take back the presidency in 2024; he would simply give the water to states that voted for him, even if that meant vast new canal systems to ship Colorado River water to Montana and Alabama.

As part of the agreement, the administration will provide about $1.2 billion in grants to cities, tribes, and irrigation districts from the Inflation Reduction Act, helping them with water conservation projects. Now that the states have agreed to cut the amount of water they use, they’ll need to determine their own ways of meeting those commitments.

And as Reuters explains, this deal is only a temporary measure that will get the states through 2026, the end of the current seven-state agreement on divvying up Colorado River water, so now it’s almost immediately back to negotiations for a plan to succeed it starting in 2027. The new agreement will have to take into account the likelihood that drought conditions will continue as climate change makes the Colorado basin warmer and more prone to drought.

“There are significantly more difficult things in the future that are going to have to be agreed to,” said John Entsminger, Nevada’s representative.

The Colorado River Compact has long been problematic as it was agreed following an usually wet period, misleading signatories into believing more water was available to them. […]

Entsminger said officials now acknowledge there will be less Colorado River water available in the 21st century than there was in the 20th.

This is where the ghost of Edward Abbey gives us all the finger and shouts “Told you so!”

But also, Entsminger points out that while Las Vegas has grown by 800,000 people since 2002, that growth has come with a 31 percent reduction in the urban area’s use of Colorado River water.

Longer term, California is planning for a hotter, drier future, with plans to more effectively capture rainwater and storm runoff so it recharges aquifers, building desalination plants powered by wind and solar, and also restricting water-wasting agricultural crops hahaha we are kidding, BUY ALMONDS and wear avocados on your acre feet.

This is also where I remind you that our Wonkette Book Club is reading Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2020 climate novel The Ministry for the Future, (Friday’s reading is Chapters 2 through 30 — they’re short!) and yes there are some very thought-provoking bits in the novel involving California’s potential water solutions and crises coming up in the book, hoo boy. More information on the Book Club here!

And now? OPEN THREAD!

[Reuters / NBC News / CBS News / Department of Interior / Photo by Jay Huang, Creative Commons License 2.0]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please give $5 or $10 monthly to help us keep bringing you innovative volume comparisons, like the fact that an acre-foot of nickels donated to Wonkette would be very welcome but would still not entice us to dive into it like Scrooge McDuck, no way.

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)