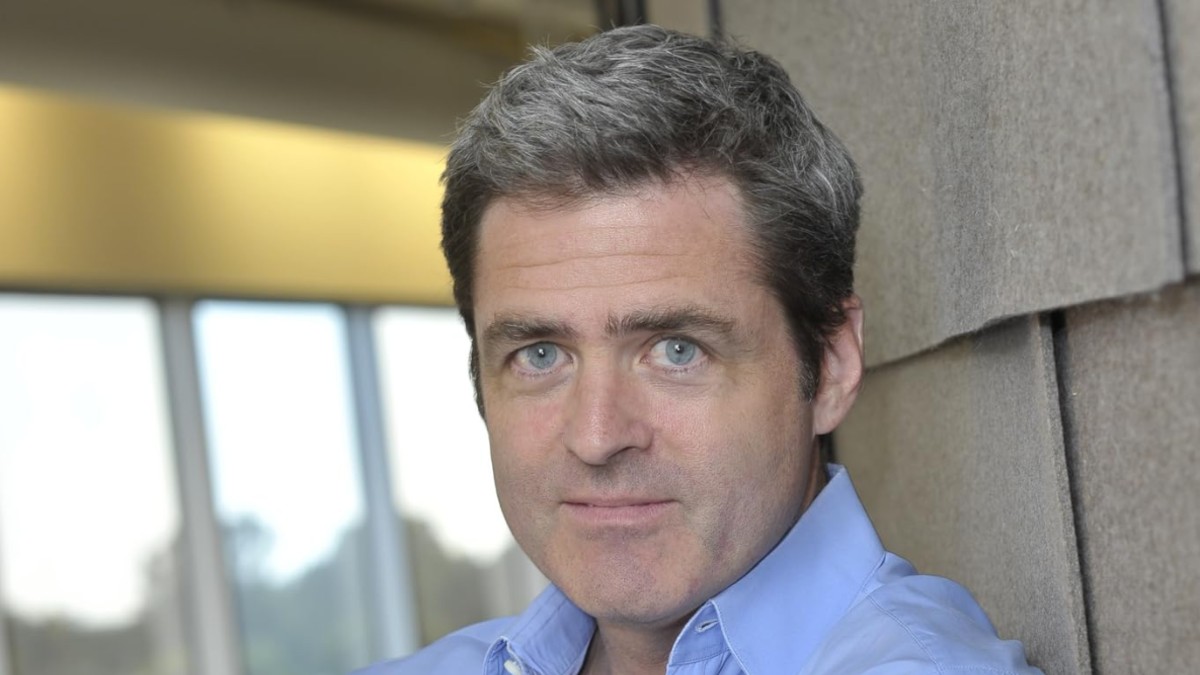

Legendary singer Tony Bennett — born Anthony Dominick Benedetto — has passed away at the age of 96 following a 70-year career being, without question, one of the coolest people on earth.

His father was a grocer and an immigrant from the Calabria region of Italy and his mother, the daughter of immigrants from the same region, was a seamstress. He grew up during the Depression, later noting that he had been a Democrat all his life because “the Hoover Administration left everybody so stranded. I have never gotten over that.” Which is pretty cool considering how many of his formerly liberal contemporaries who shall not be named later supported Ronald Reagan.

A lot of people, they get older, they get rich, they forget and they get more conservative, but Tony Bennett was not one of them.

Bennett has been described in a bunch of headlines today as a Champion of the Great American Songbook — which he was. In fact, he’s probably the reason a lot of younger people know the classic jazz standards he performed with Amy Winehouse …

Lady Gaga …

… Christina Aguilera, and more.

But he was also a champion of civil rights.

Like many of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers, Bennett served in the military during World War II — and in fact helped to liberate Dachau — but was demoted from corporal to private for the great transgression of inviting a Black friend to sit with him to eat at Thanksgiving.

In Mannheim, he ran into an old friend from the High School of Industrial Arts in New York City, where, as Bennett explains, poor Depression kids got a chance to “pull ourselves up by our bootstraps.”

Bennett’s old friend Frank Smith was African American. They had played music together in high school and were overjoyed to find each other in the wreckage of Europe. Bennett says simply, “We loved one another very much.”

Bennett invited Frank back to dinner. There a captain called Bennett over, took out a razor blade, cut off his corporal stripes, threw them on the ground, spat on them and declared, “You’re shipping out in 20 minutes. We don’t like the company you keep.” Bennett was reassigned to graves registration, a gruesome job, digging up and identifying bodies — all because his friend was black.

“This was another unbelievable example of the degree of prejudice that was so widespread in the army during World War II,” Bennett later wrote in his autobiography. “Black Americans have fought in all of America’s wars, yet they have seldom been given credit for their contribution, and segregation and discrimination in civilian life and in the armed forces has been a sad fact of life.”

“It was actually more acceptable to fraternize with the German troops than it was to be friendly with a fellow Black American soldier,” he added.

It was his experience in WWII that made him a pacifist and led to a lifelong opposition to war.

“The main thing I got out of my military experience was the realization that I am completely opposed to war,” he wrote. “Every war is insane, no matter where it is or what it’s about. Fighting is the lowest form of human behavior. It’s amazing to me that with all the great teachers of literature and art, and all the contributions that have been made on this very precious planet, we still haven’t evolved a more humane approach to the way we work out our conflicts. Although I understand the reasons why this war was fought, it was a terrifying, demoralizing experience for me. I saw things no human being should ever have to see.”

He later described the war in Iraq as a “a tremendous, tremendous mistake internationally.”

Bennett marched in Selma alongside Sammy Davis Jr. and his good friend Harry Belafonte, to whom he attributed his understanding of civil rights issues at that time, growing from “Hey, I just want to sit with my good friend at Thanksgiving” to really seeing the wider implications of structural racism.

Following the march, Bennett was dropped off at the airport by civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo, who was murdered later that day by members of the Ku Klux Klan.

Musically, the thing about Tony Bennett is that he just sang. He never sounded like he was trying to sing, like he was trying to dazzle anyone with his talents, like he was trying to make the teenyboppers faint — he just sang in such a relaxed and natural way and it was just lovely.

In the ‘60s and later, he was encouraged to sing rock covers and other songs more in line with the times, but that’s not what he did so he didn’t. Which is good, because that could have gone really wrong. He did, however, do a pretty fantastic version of Stevie Wonder’s “For Once In My Life.”

Here is one of my Nonnie Marie’s favorites — she got to see him live when she was younger, which she was fond of mentioning (though no one threw a tomato at him like they did when she saw Sinatra).

And here’s one of mine, even though I’ve never seen him live or seen anyone get hit by a tomato (while on stage, anyway).

He was a good person and he lived a good life, and he will be missed.