The US Supreme Court on Thursday upheld the law that gives Native American tribes preference in adoption and foster care cases involving Native children, rejecting the argument that it’s racist against white people. In a 7 to 2 decision, the Court let stand the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), which Congress wrote to address concerns that Native kids were being taken away from their families, a legacy of the US government’s attempts to wipe out Native American tribes through forced assimilation. The ’70s were a crazy time, with the disco and the occasional congressional efforts to provide at least some justice for past discrimination.

Previously

Will Supreme Court ‘Increase Domestic Supply Of Infants’ By Stealing Native American Babies?

You Guys, The Fifth Circuit Ruled *For* The Welfare Of Indian Children

What The Hell Is It With Republicans Crapping On Native Americans?

Under the ICWA, as Vox explainered, if a child is a member of a Native American tribe or even is eligible for membership, then any adoption or foster placement needs to give first preference to the child’s extended family, and then to another Native American family, ideally in their own tribe or if necessary another tribe.

The law aims to keep Native children within Native communities, after over a century of US attempts at genociding Native Americans and, for most of the 20th century, actively attempting to alienate people from their tribal identities — first by taking Native kids from their families to Indian schools that aimed to assimilate them into the dominant Anglo culture, and later by encouraging adoptions of Native kids by white parents.

(A quick note on language here: Federal law and court cases use the term “Indian,” which has very specific meanings in law, so at times we will too, even if in the wider culture it’s no longer the preferred nomenclature, Dude.)

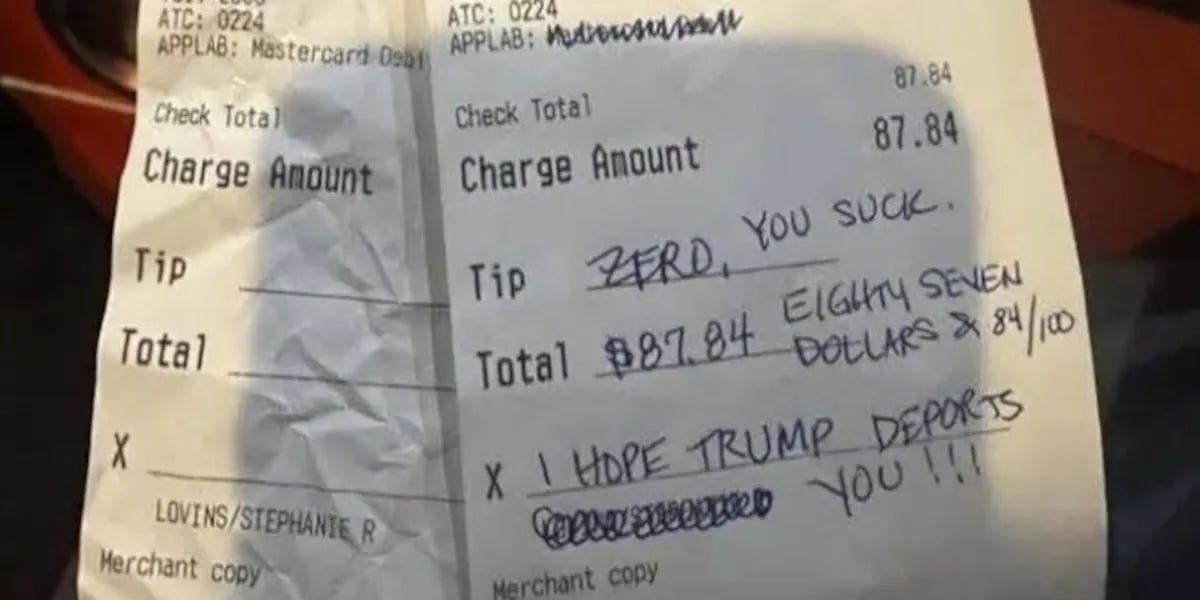

The case, Haaland v. Brackeen, has been making its way through the federal courts for years. It involves a white Texas couple, Jennifer and Chad Brackeen, who in 2016 were appointed as foster parents of a 10-month-old boy whose birth parents were Navajo and Cherokee. God told the Brackeens they needed to adopt the boy, but they found themselves in a legal fight with the Navajo Nation. Eventually they did adopt the boy, but they also wanted to adopt his half-sister, and here we are at the Supreme Court, with the Brackeens and the state of Texas (and a few other plaintiffs) arguing that the 1978 law was unconstitutional because it was an illegal racial preference and discriminated against non-Indian parents, and that by superseding state family law courts, Congress had overreached.

Ultimately, though, the Court, in an opinion written by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, rejected that claim, as the New York Times explains:

The tribes have said that they are political entities, not racial groups. Doing away with that distinction, which underpins tribal rights, they argued, could imperil nearly every aspect of Indian law and policy, including measures that govern access to land, water and gambling.

The majority dismissed the equal protection argument, saying that no party in the case had legal standing. Instead, the justices focused on Congress’s longstanding authority to make laws about tribes. […]

“Our cases leave little doubt that Congress’s power in this field is muscular, superseding both tribal and state authority,” Justice Barrett wrote, adding that its authority touched on subjects as varied as criminal defense, domestic violence, property law, employment and trade. She added, “The Constitution does not erect a firewall around family law.”

The two dissenting justices, Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, each wrote their own dissents. Alito griped that the law focused too much on the tribes’ rights and not the right of the child to have the best family, which we presume was shorthand for a white family, because we’re just that mean. Thomas was his usual “government overreach, boo, hiss!” self, contending that the law wasn’t fair because some of the Native kids involved in adoptions regulated by the ICWA “may never have even set foot on Indian lands.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch, who’s been consistently friendly to Tribal interests in federal law, wrote a concurring opinion in which he said the majority opinion “safeguards the ability of tribal members to raise their children free from interference by state authorities and other outside parties.” Gorsuch explained that he agrees completely with the majority, but also wanted to provide “some historical context” with an overview of “how our founding document mediates between competing federal, state, and tribal claims of sovereignty.”

Here’s his introduction, which genuinely makes me want to read the rest this weekend.

The Indian Child Welfare Act did not emerge from a vacuum. It came as a direct response to the mass removal of Indian children from their families during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s by state officials and private parties. That practice, in turn, was only the latest iteration of a much older policy of removing Indian children from their families—one initially spearheaded by federal officials with the aid of their state counterparts nearly 150 years ago. In all its many forms, the dissolution of the Indian family has had devastating effects on children and parents alike. It has also presented an existential threat to the continued vitality of Tribes—something many federal and state officials over the years saw as a feature, not as a flaw. This is the story of ICWA.

Well yeah, that’s all impressively true, which led to a very reasonable question from “Southpaw” on Twitter: How the hell is it that Gorsuch is

so attuned to—and frankly eloquent at exposing—structural racism in Indian affairs, but so seemingly indifferent to it in other aspects of American life?

New Republic legal writer Matt Ford suggested that it comes down to Gorsuch’s weird originalism, pointing out that in his concurrence, Gorsuch writes,

Our Constitution reserves for the Tribes a place—an enduring place—in the structure of American life. It promises them sovereignty for as long as they wish to keep it. And it secures that promise by divesting States of authority over Indian affairs and by giving the federal government certain significant (but limited and enumerated) powers aimed at building a lasting peace.

Bummer for anyone else who’s faced systemic discrimination, though. You people should have found a way to get yourselves into the Constitution, and don’t you go saying “the 14th Amendment” because that’s not specific enough. He’s an odd one.

In a statement, President Joe Biden celebrated the Court’s decision, pointing out that he had supported the ICWA when he was in the Senate, he’s so old. Biden also did his own Critical Race Theory, noting that

Our Nation’s painful history looms large over today’s decision. In the not-so-distant past, Native children were stolen from the arms of the people who loved them. They were sent to boarding schools or to be raised by non-Indian families—all with the aim of erasing who they are as Native people and tribal citizens. These were acts of unspeakable cruelty that affected generations of Native children and threatened the very survival of Tribal Nations. The Indian Child Welfare Act was our Nation’s promise: never again.

So now all we have to do is worry what this pretty reasonable decision, combined with one that didn’t strike down the Voting Rights Act in its entirety last week, means for the next bunch of decisions coming from the Court, not that we’re cynical that way. Maybe it’ll decide not only to strike down Biden’s student loan forgiveness program, but also to eliminate student aid going forward because George Washington never got a student loan, now did he?

[AP / NYT / Vox / Haaland v. Brackeen / Photo: Jarek Tuszyński, Creative Commons License 3.0]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please give $5 or$10 a month so we can keep bringing you all the court news you can fit in your briefs. Just don’t stare at our decisis.