[ad_1]

“It would indeed be a difficult matter to find anything which is productive of more marvelous effects than the menstrual discharge. On the approach of a woman in this state, must will become sour, seeds which are touched by her become sterile, grafts wither away, garden plants are parched up, and the fruit will fall from the tree beneath which she sits. Her very look, even, will dim the brightness of mirrors, blunt the edge of steel, and take away the polish from ivory. A swarm of bees, if looked upon by her, will die immediately; brass and iron will instantly become rusty, and emit an offensive odor; while dogs which may have tasted of the matter so discharged are seized with madness, and their bite is venomous and incurable.” — Pliny The Elder

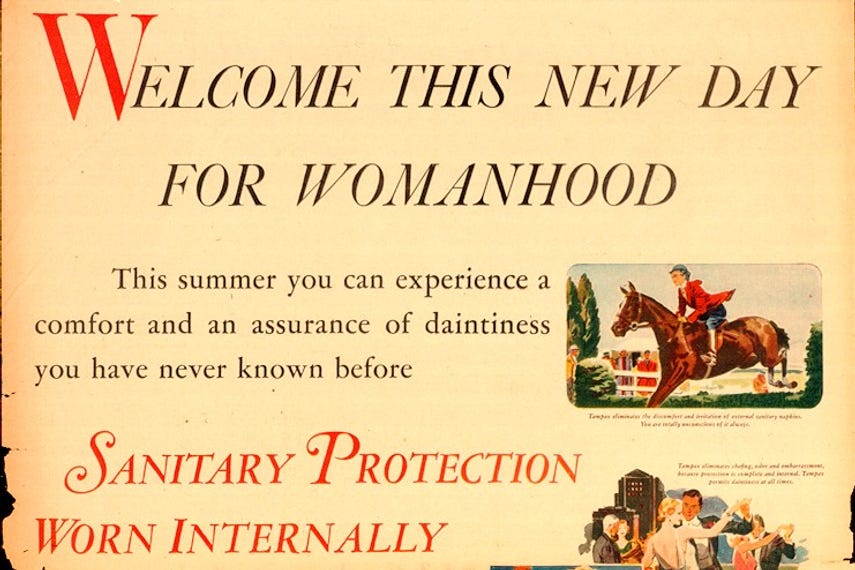

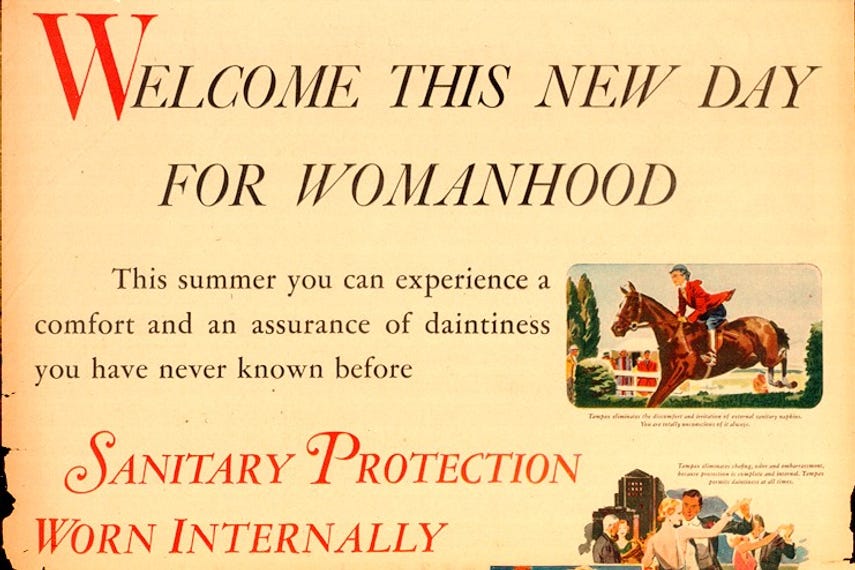

As convenient as that bee murder thing would be in a My Girl-esque emergency, it is pretty bananas that a scientific-minded fella like Pliny The Elder, even in the first century, would seriously think this is what happens during menstruation. Unfortunately, while few worry about our effect on crops these days, actual scientific research on menstruation is still relatively scant, as is the case with many conditions that primarily affect women, including migraines, endometriosis, and anxiety disorders.

There has been a known research (and funding for research) gap forever when it comes to these conditions, or to understanding how conditions that affect everyone specifically affect those assigned female at birth. But things are starting to get better. As Vox reported this week, we are finally starting to get some more serious research into menstruation and its effects (the real ones, not the mirror-dimming ones).

Via Vox.com:

In one recent study, psychologist Jaclyn Ross and a team at the University of Illinois Chicago asked 119 female patients who had experienced suicidal thoughts in the past to track their feelings over the course of a menstrual cycle. They found that for many patients, suicidal thoughts tended to get worse in the days right before and during menstruation. On those days, patients were more likely to progress from thinking about suicide to actually making plans to end their own lives.

These patients, notably, did not have premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a condition that causes severe anxiety, depression, and irritability, as well as a tendency to feel very sure that all of your friends and family members are only pretending to like you out of pity and to have three hour panic attacks over pretty much nothing. Not that I would know anything about that.

The researchers wanted to see, specifically, how menstruation can affect people who don’t have the disorder but do have a history of suicidal ideation.

Ross’s study, published in December in the American Journal of Psychiatry, suggests that therapists, psychiatrists, and OB-GYNs should be giving patients information about how menstruation can affect emotional symptoms, especially suicidality. Patients might also benefit from charting their own symptoms for a few months to see whether a cyclical pattern emerges.

This would be very helpful! There’s something very, very helpful, I think, about understanding that there is a reason your brain is making you feel a certain way. Or just knowing that it could happen ahead of it happening.

Researchers are also exploring whether menstrual fluid could be used in early detection of conditions like uterine fibroids, cancer, and endometriosis. Studying menstruation, in which the uterus sheds and regrows its own lining, could provide insight into wound healing, midwife and author Leah Hazard told Vox’s Byrd Pinkerton.

In the last two years, researchers have also confirmed what many patients reported anecdotally: that Covid-19 vaccines have small but measurable effects on menstrual cycles. The findings could push vaccine manufacturers to test their products’ effects on menstruation so that patients won’t be caught off guard. (The menstrual effects of the Covid vaccine are temporary and do not impact fertility, experts say.) […]

In 2023 — yes, last year — researchers finally conducted one of the first studies to test the capacity of menstrual products using real blood.

What? Instead of just dunking them in Cool Blue Gatorade? Revolutionary!

As Caroline Criado Perez, author of Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, has noted “[f]or millennia, medicine has functioned on the assumption that male bodies can represent humanity as a whole,” with most research for most conditions being studied on cis men. So not only have we not had a lot of research on menstruation, we’ve barely had any on how menstrual issues can impact other conditions. Hell, we haven’t had a lot of research into how being a woman can impact other conditions, period (no pun intended).

For instance — not to get too personal, but I have both PMDD and ADHD. There is some research showing that both PMDD and postpartum depression are significantly more common in those who have ADHD, but zero research into why that might be. This is hardly surprising given that, for decades, all research into ADHD was focused on how it affected boys and men. But it would certainly make sense to have more information and research on something like this, so that doctors could make an extra effort to let patients know or to check for symptoms of either. Everything doesn’t have to be a feminine mystery.

There has been a long-running problem with doctors not listening to women (Black women especially) when they say something is wrong. Anecdotally, I know lots of women who have had serious issues with their periods or other health concerns who have been blown off by their doctors as not a big deal or treated in a way that was not helpful. Hell, I still cannot get over the fact that my doctor gave me Vicodin for cramps when I was 15 (didn’t help, either, but birth control did!). A lot of that is because of sexism (or both sexism and racism), but some of it is likely because there just isn’t enough information available. This can lead to women either not trusting their doctors or not saying when something is wrong for fear they’ll be dismissed. That’s not good!

Things are definitely improving and these new studies are proof of that, but there’s a lot of catching up to do, a lot of years where women’s health studies were underfunded and women were underrepresented in clinical trials. And, hopefully, someday, someone will find out how I made all of my kitchen knives dull just by looking at them.

PREVIOUSLY:

[ad_2]

Original Source Link