Last week, Donald Trump responded to the government’s proposed trial date of December 11, 2023 with a counteroffer. He proposed setting it for NEVER. Or, if not never, sometime after the 2024 election.

Trump’s lawyers Chris Kise and Todd Blanche put forth several reasons to disregard the Southern District of Florida’s speedy trial requirement that cases begin within 70 days of the indictment. Indeed, Judge Aileen Cannon herself set a date of August 14, meaning that the government’s proposal amounts to a four-month extension.

“This case presents a serious challenge to both the fact and perception of our American democracy” they huffed indignantly, before setting out a veritable roadmap of all the bullshit they intend spew in an effort to fight off Special Counsel Jack Smith’s 38-count indictment:

The intersection between the Presidential Records Act and the various criminal statutes at issue has never been addressed by any court, and in the Defendants’ view, will result in a dismissal of the indictment. The authority, vel non, of the Special Counsel to maintain this action likewise presents a potentially dispositive issue of first impression in this Court. Additional significant matters include the classification status of the documents and their purported impact on national security interests, the propriety of utilizing any “secret” evidence in a case of this nature, and the potential inability to select an impartial jury during a national Presidential election. Moreover, the extensive and voluminous discovery, coupled with the challenges presented by the purportedly classified material that has yet to be produced, will require significant time for review and assimilation.

In short, they intend to waste a year making the idiotic argument that the National Archives had to ask nicely for Trump to return that stuff in perpetuity; that the Special Counsel law is unconstitutional; and that the warrant was defective. And if none of that works, they’ll say he can’t be tried during the election, paving the way for Trump to pardon himself from the Oval Office on January 20, 2025.

To be clear, the Speedy Trial Act is an IRL law enacted to protect the rights of defendants and grounded in the Sixth Amendment, not, as Trump implies, a procedural “gotcha” to allow the government to force defendants to face a reckoning before they’re ready. There is simply no precedent for allowing a defendant to take the trial date off the calendar entirely. That is not a thing.

“A speedy trial is a foundational requirement of the Constitution and the United States Code, not a Government preference that must be justified,” the government responded Thursday.

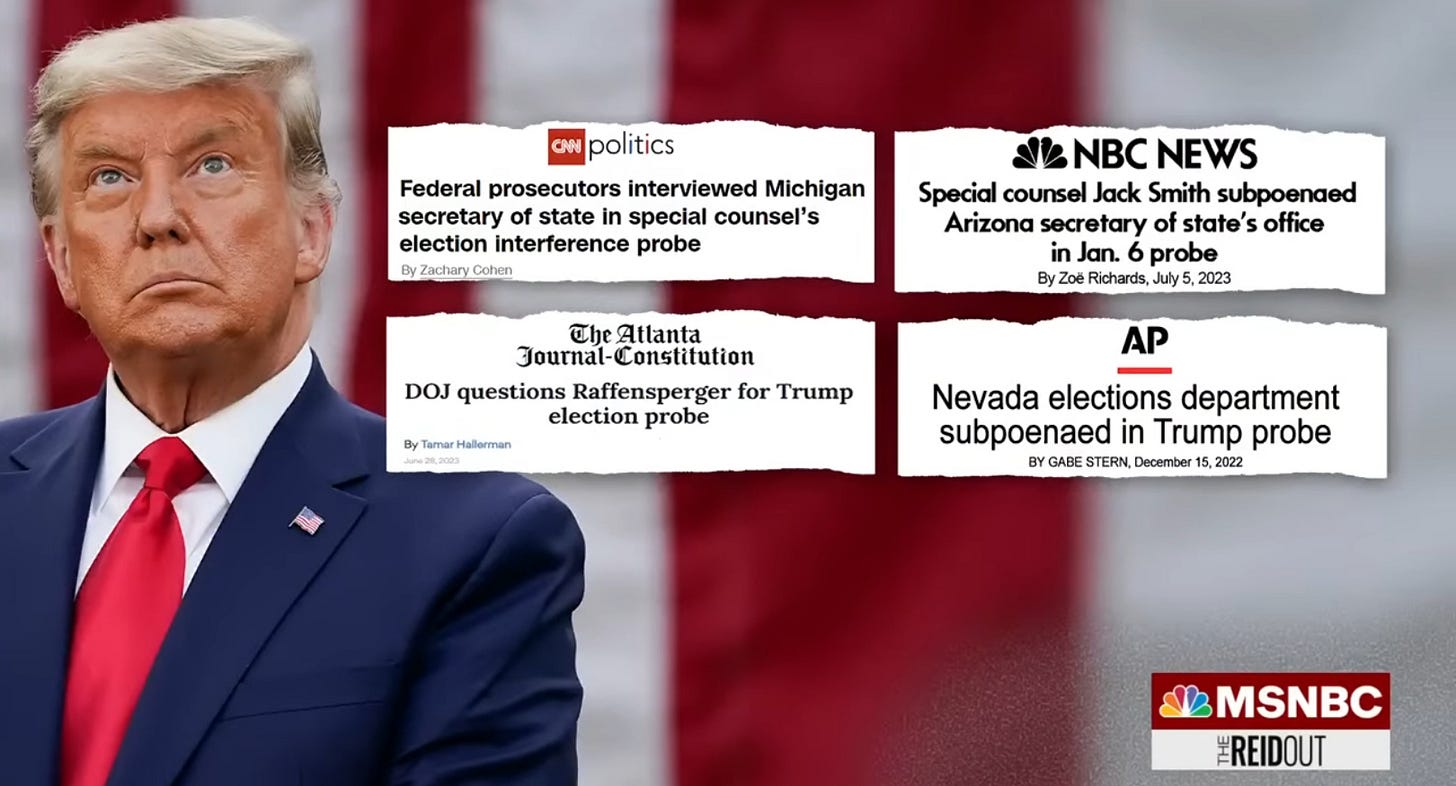

Unsurprisingly, the government also disagrees with Trump’s position that “The legal questions are significant and present issues of first impression.” As prosecutors note, the PRA was passed in 1978 to stop Nixon from taking his papers with him and destroying evidence of crimes, while the special counsel laws were already upheld during the Mueller investigation.

“The Defendants are, of course, free to make whatever arguments they like for dismissal of the Indictment, and the Government will respond promptly,” they responded Thursday. “But they should not be permitted to gesture at a baseless legal argument, call it ‘novel,’ and then claim that the Court will require an indefinite continuance in order to resolve it.”

As for Trump’s complaint that the volume of evidence in the case militates in favor of delay, the government says that Trump left out a few important details regarding “steps the Government has taken to make the Defendants’ review as efficient as possible.” These include producing everything immediately, and indexed to highlight the “key documents referenced in the Indictment or otherwise determined by the Government to be pertinent to the case.” Similarly, Trump’s complaint about “nine months of CCTV footage” is deceptive in that it omits to mention both that the government has flagged the “key” bits of the tape, and anyway the cameras are motion activated, so there’s not that much to watch.

But Trump’s argument that the classified evidence in this case means that it should be indefinitely delayed and/or that the Classified Information Procedures Act (CIPA) should not apply to Trump, really seems to have set the government off.

Last week Trump wrote: “In general, the Defendants believe there should simply be no ‘secret’ evidence, nor any facts concealed from public view relative to the prosecution of a leading Presidential candidate by his political opponent. Our democracy demands no less than full transparency.”

This would appear to suggest that, after pocketing upwards of 100 classified documents, Trump can force the government declassify those documents if it wants to prosecute him. True to form, Trump thinks that a law specifically enacted to solve the problem of graymail — that is, defendants threatening to reveal classified information in open court if the government prosecuted them — should not apply to him.

Defendants also twice raise the specter of “secret” evidence and state their opposition to “any facts being concealed from public view . . . .” Resp. at 2, 6. If Defendants intend to seek permission to disclose classified information to the public, that would be the very type of “graymail” CIPA was enacted to prevent.

Meanwhile, Jack Smith moved this afternoon for a further protective order in addition to the one already signed by the magistrate judge. He suggests that Trump’s lawyers have been uncooperative, making generalized objections to the government’s proposal to protect discovery, but refusing to spell out what those objections are. (Presumably because they either don’t think CIPA should apply their client, or because they don’t want to be on the hook if and when he violates a court order and posts classified documents on Truth Social.)

But, as the government points out, Judge Cannon has very little discretion here, since the statutory language says “shall,” not “may.”

Section 3 of CIPA provides that the Court shall issue an order, upon the request of the United States, “to protect against the disclosure of any classified information disclosed by the United States to any defendant in any criminal case.” In contrast to the discretionary authority in Rule 16(d)(1), Section 3 of CIPA provides that, when classified information is involved, protective orders are to be issued whenever the government discloses classified information to a defendant in connection with a prosecution.

And if memory serves, part of the reason Judge Cannon got slapped down by the Eleventh Circuit last year was that she didn’t want to treat classified documents any differently from the rest of the evidence seized in the RAID on Mar-a-Lago.

All of which should make for a fun hearing tomorrow when the parties meet to discuss how they’re going to handle CIPA. Although, not so fun for us, since Judge Cannon just banned reporters from bringing cell phones and laptops into the hearing.

Almost like she’s about to start doing crazy shit for Trump, and she doesn’t want it broadcast live, right?

[US v. Trump,Docket via Court Listener]

Catch Liz Dye on Opening Arguments podcast.

Click the widget to keep your Wonkette ad-free and feisty. And if you’re ordering from Amazon, use this link, because reasons .

![Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic] Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/9e7sW3TubFHM00yvXe5zvvbhAVriJiGqS8xmVFLPC6s/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zb2NpYWxfc3ByaW5nX2NsZWFuaW5nMi5wbmc=.webp)

![5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic] 5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/Hv-m77iIkXSAtB3IEwA3XAuouMwkZApIeDGDnLy5Yhs/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9saW5rZWRpbl9zdHJhdGVneV9pbmZvMi5wbmc=.webp)