The Big Picture

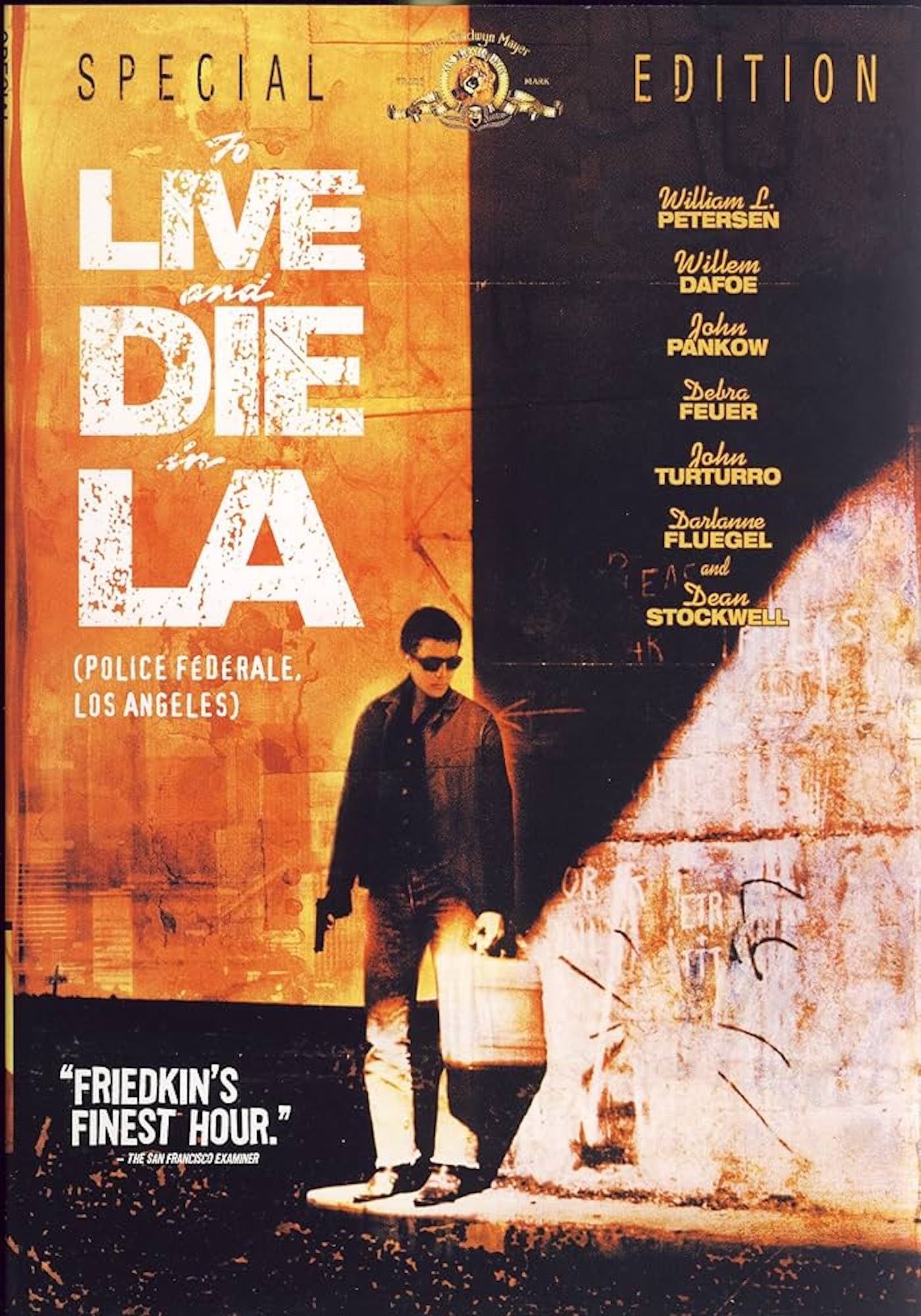

- To Live and Die in L.A. is a dark and harrowing film that taps into the gritty and corrupt nature of society, showcasing the rot that consumes powerful institutions and individuals.

- The movie explores themes of systemic corruption and the bleakness of existence, highlighting how nobody is truly in control and how random horrors can befall anyone.

- William Friedkin’s willingness to use bright bursts of color in his films adds visual variety and counterpoints the grim world depicted in To Live and Die in L.A., making it an extraordinary visual exercise and a timeless piece of thought-provoking cinema.

The New Hollywood movement opened up doors for bleaker storytelling in American cinema. Specifically, it allowed, in the wake of the Hays Code dissolving, for authority figures like cops to finally be depicted as out-and-out baddies on film. The darker complexities of reality, where authority figures often become evildoers, could be brought to life on the silver screen. Filmmaker William Friedkin leaned into these possibilities and then some with his 1971 feature The French Connection, while subsequent 1970s directorial efforts like The Exorcist and Sorcerer would dabble in material that would’ve been unthinkable to witness in American cinema just a decade earlier. Friedkin’s love for capturing the grimy underbelly of humanity endured well into the 1980s when he helmed the 1985 feature To Live and Die in L.A.

Much like The French Connection, To Live and Die in L.A. chronicles a pair of law enforcement officers (NYPD detectives in Connection, Secret Service agents in L.A.) trying to stop a reputable criminal. However, To Live and Die in L.A. quickly takes on a vivid life of its own away from that 1971 Best Picture Oscar winner. The New Hollywood movement was well over by 1985. However, with To Live and Die in L.A., Friedkin was able to tap into incredibly dark and harrowing filmmaking that epitomized all the risk-taking and norm-shattering that era of Hollywood’s history stood for.

To Live and Die in L.A.

A fearless Secret Service agent will stop at nothing to bring down the counterfeiter who killed his partner.

- Release Date

- November 1, 1085

- Runtime

- 116m

- Main Genre

- Crime

Corruption Is Everywhere in ‘To Live and Die in L.A.’ Including in Powerful Institutions

William Friedkin’s movies show he’s not interested in heroes. The quartet of morally compromised men at the heart of Sorcerer is a great example of this, as are the bleak souls anchoring The French Connection. To Live and Die in L.A. continues this trend ten-fold, with protagonist Richard Chance (William Petersen) never getting depicted as heroic for bending the rules and engaging in criminal activity to take down money counterfeiter “Rick” Masters (Willem Dafoe). Chance is blinded by a craving for full-throttle revenge after Masters killed his partner. This desire sends the character down a rabbit hole of bottomless corruption that epitomizes the dark morality that defined so many of Friedkin’s most unforgettable works.

What’s especially fascinating about To Live and Die in L.A.’s depiction of rampant corruption is how it seeps into everything. Attorney Bob Grimes (Dean Sockwell) is quite nonchalant about breaking attorney/client privilege, while Chance’s superiors often give in to his tantrums and let him off with a slap on the wrist rather than engage in more severe punishments for his horrific transgressions. Meanwhile, Friedkin depicts cops engaging in violent tactics first and foremost to get vital information out of potential suspects. Such moments are captured in very unembellished wide shots, an element that accentuates the chilling nature of such moments. Through these stories and visual details, To Live and Die in L.A. cements that it is not depicting “just one bad apple” as the problem in society. Chance is emblematic of larger systemic issues, a rot that is consuming all it touches.

The William Friedkin Movie That Made 50 Crew Members Sick

The director of ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The French Connection’ came down with malaria himself during this rough shoot.

The depiction of wall-to-wall debauchery within powerful institutions in To Live and Die in L.A. is taken to the next level when Peterson and his partner John Vukovich (John Pankow) attempt to steal $50,000 from a man apparently coming into Los Angeles to pick up stolen diamonds. This robbery, done to secure the money that will bring the duo closer to Masters, quickly goes wrong, with Friedkin’s filmmaking and screenplay (the latter of which was also penned by Gerald Petievich, who also wrote the feature’s source material) depicting the pair flying by their seats trying to drive away from gunmen also interested in this $50,000. There is no clear planning here from the characters, they’re just swerving around the road with no consideration for how their actions impact the citizens they’re supposed to “protect.”

Friedkin wasn’t just obsessed with morally bleak characters or systemic corruption. His works also considered the terrifying randomness of existence. This is reflected by how nobody’s really in control in this particular gripping chase scene from To Live and Die in L.A. and the rest of the movie. Not even the guy who prints money can fully calculate what his opponents will do next or take out incarcerated souls who may squeal on him. Friedkin’s camera is focused on a world where not only are those in power corrupt, but random horrors can befall any soul at any time. It’s the only thing uniting people across all classes, ages, and occupations. These themes kept showing up through Friedkin’s filmography and they’re especially vividly rendered in his work on To Live and Die in L.A.

‘To Live and Die in L.A.’ Shines a Light on Griminess

Many filmmakers, especially in the modern world, mistake dark stories for ones that need rampantly incomprehensible lighting. Dimness is confused as a substitute for thematic depth or actually stirring cinematography. William Friedkin’s features plumbed the darkest depths of humanity, but they also weren’t coated in wall-to-wall darkness. On the contrary, some of the most stirring images in his features were defined by expertly placed bright lighting. Just look at the most iconic shot of The Exorcist, which features a beam of light pouring from a possessed girl’s bedroom onto a priest on the street below. Meanwhile, one of the final shots of Sorcerer sees Jackie Scanlon (Roy Scheider) arriving at his destination and collapsing to his knees in front of a gigantic pillar of fire spewing into the pitch-black night. The simmering and vivid streak of orange cascading in the background emphasizes the weariness of Jackie Scanlon, who has none of the energy of this gushing fire.

Friedkin’s willingness to embrace bright bursts of color in his works didn’t undercut the bleak tones of his features. On the contrary, they offered up a greater level of visual variety that made his films feel even more like they occupied reality. To Live and Die in L.A. is a masterclass in this quality, as the saga of Peterson and Masters is dominated by interior environments soaked in bright colors. The entrance to a strip club is coated in bright red and green lighting, every inch of the sauna is covered in violet hues, and Masters uses red-painted Chinese symbols as a calling card.

These bright colors provide a fantastic counterpoint to the grim world the characters of To Live and Die in L.A. inhabit. Even amongst all the settings dominated by conceptually cheerful colors, graphic violence, and deception is occurring. Treachery has seeped so deep into the world of To Live and Die in L.A. that violence and betrayal aren’t just transpiring in dim alleyways and seedy locales. Meanwhile, shadows are also beautifully executed within the visual landscape of this production. A key moment where a shaken Vukovich returns to his car wouldn’t be so harrowing without the sequence’s masterful handling of when this figure is visible to the viewer and when he’s been consumed by shadows. These kinds of vivid images make To Live and Die in L.A. an extraordinary visual exercise and an encapsulation of the kind of thoughtful imagery found throughout Friedkin’s body of work.

Why ‘To Live and Die in L.A.’ Debuting in the ’80s Matters

By 1985, the era of New Hollywood had been wiped out for several years. Rampant mistrust of authority in the wake of the Vietnam War and Watergate that underscored Friedkin’s big 1970s dramas had also vanished. In its place was a country molded in the image of President Ronald Reagan, where the “greatest enemy” was “welfare queens” and the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Figures in authority were now meant to be loved and cops especially were meant to be empowered as much as possible. Any hopes from the preceding two decades of instilling long-term chance were wiped out in a social climate that hammered home the importance of maintaining the status quo.

1980s cinema often reinforced this political climate, including conservative-leaning features like the massive 1985 blockbuster Rambo: First Blood: Part II. The world looked a lot different than it did in 1971 when The French Connection came out, but that just made the subversive qualities of William Friedkin’s filmmaking obsessions all the more important. In a decade of cinema and political police where cops were lionized, here was Friedkin delivering a feature where trigger-happy cops do not solve all of society’s ills. On the contrary, it’s often impossible to tell the heroes from the villains (if even such differentiation exists) in To Live and Die in L.A. The ending of the feature, in which Vukovich responds to witnessing brutal violence by submersing himself deeper into lawlessness, extends this bleak outlook right to when the credits begin to roll. Even seemingly good souls like Vukovich can be corrupted. No figures in power are safe from becoming what they once hated.

That kind of grimness ran counter to the vibes of the most popular movies of 1985 like Rocky IV and The Goonies. It undoubtedly influenced why, initially, audiences just couldn’t quite crack what To Live and Die in L.A. was aiming for. It seemed to come from another planet compared to the cinematic norms of 1980s cinema despite being rooted in the themes and questioning of authority that had defined mainstream movies just a decade earlier. However, To Live and Die in L.A.’s relentlessly bleak outlook on secret service agents just made it an even more compelling crime thriller. By eschewing the standards of 1980s action fare, this motion picture transformed into a gripping yarn that just oozed unpredictability. Its tone also crystallized how Friedkin’s subversive filmmaking would always endure even in an era outright hostile to questioning figures in positions of authority. The New Hollywood era had run its course, but Friedkin wasn’t abandoning the transgressive qualities that had turned him into an icon in the first place. His commitment to those ideas may not have made him a 1980s box office champion, but it did solidify him as a filmmaker for the ages. The world of American cinema is so much richer thanks to Friedkin’s dedication to the kind of grimy and thought-provoking filmmaking on vivid display throughout To Live and Die in L.A.

To Live and Die in L.A. is available to purchase on Amazon Prime in the U.S.

![Instagram Shares Tips on What to Avoid to Maximize Post Reach [Infographic] Instagram Shares Tips on What to Avoid to Maximize Post Reach [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/oeaypf55nGOsin6XxBa9EFYmwtVEiffkp9q_OiAPUGM/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9pbnN0YWdyYW1fZGlzdHJpYnV0aW9uX2luZm9ncmFwaGljMi5wbmc=.webp)