The Big Picture

- Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata once dreamt of adapting the Pippi Longstocking book series into a feature-length film before creating Studio Ghibli.

- Miyazaki and Takahata were passionate about the project, even flying to Sweden to meet with Astrid Lindgren, the author of the Pippi Longstocking books.

- Unfortunately, Lindgren refused to see them, and without her permission, the Pippi Longstocking film never came to fruition. However, elements of Pippi’s inspiration can still be seen in their finished works.

In an alternate universe, the first animated adaptation of Astrid Lindgren’s beloved children’s character Pippi Longstocking might also have been one of the first Studio Ghibli films. Years before they founded the world-renowned animation studio and created masterpiece after masterpiece of the medium, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata once dreamed of adapting the Pippi Longstocking book series into a feature-length film. (Since Ghibli wasn’t yet a twinkle in the duo’s eyes, this Pippi movie would have technically been Studio Ghibli-adjacent). The pair were so passionately invested in the idea, they created intricate, lovingly detailed artwork and scouted locations in Lindgren’s native Sweden. But what seemed on the surface like a perfect combination — that of Hayao Miyazaki and a spirited heroine — never evolved beyond that artwork. What happened to prevent a Studio Ghibli Pippi Longstocking from taking flight?

What Are the ‘Pippi Longstocking’ Books About?

Circa the early 1970s, Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata were experienced animators. The pair had met on Takahata’s feature film debut The Great Adventure of Horus, Prince of the Sun in 1968. Each contributed to anime television series over the subsequent years. Miyazaki wouldn’t debut as a feature film director until 1979’s The Castle of Cagliostro, and the duo wouldn’t co-found Ghibli with producer Toshio Suzuki until 1985. The studio’s first film, Castle in the Sky, arrived a year later. (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was produced by the Topcraft animation studio even though it’s honorarily included in the Ghibli canon.)

This history and future are both tied to their failed Pippi Longstocking project. By the late 1970s, both animators were thoroughly invested in adapting Astrid Lindgren’s internationally bestselling series into the animation medium. Lindgren’s creation is a tenacious, audacious, and imaginative nine-year-old redhead who also happens to be the “strongest girl in the world.” The daughter of a pirate captain, she lives by her own means and has no interest in growing up, far preferring her established life of adventure, and likewise has no patience for the foolishness of adults. She’s a call-it-like-she-sees-it girl, one who breaks social constrictions and mocks social norms, or just ignores them entirely.

For all her blitheness, however, Pippi is considerate, loving, and wise beyond her years. As she muses to herself, “If you are very strong you must also be very kind.” Lindgren initially invented the character of Pippi for her daughter Karin before writing the published works. The first book, titled just Pippi Longstocking, debuted in 1945. Since then, the series has sold millions of copies worldwide, charming and resonating with children and adults of like minds everywhere.

Why Was Hayao Miyazaki Interested in Adapting Pippi Longstocking?

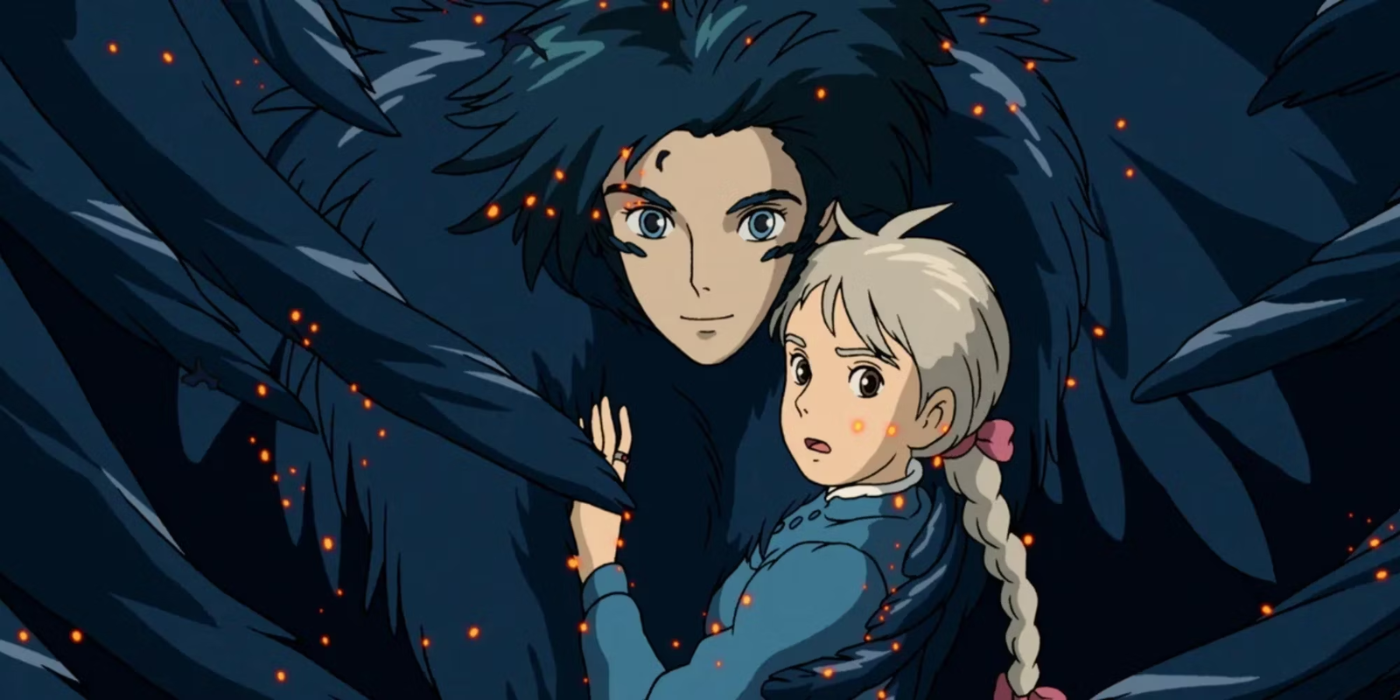

Cut to the aforementioned late ’70s. At the time, Miyazaki and Takahata worked for another animation studio and began eagerly collaborating on the possibilities of an animated Pippi Lockstocking adaptation. Examples like Kiki’s Delivery Service and Spirited Away were years away yet, but given Miyazaki’s admiration for complex girl heroes, it’s no wonder that Pippi appealed to him in particular. His love for the feisty, joyful character shines through in the film-that-never-was’s concept art, which is available online courtesy of the Ghibli LiveJournal page.

The clearest and most reputable English source about the film’s development and its cancelation is Astrid Lindgren’s official website, which in turn credits observations translated from The Phantom Pippi Longstocking book published by Studio Ghibli in 2014. According to both, the trio of Miyazaki, Takahata, and influential animator Yasuo Ōtsuka were passionate enough to fly to Sweden for a planned meeting with Lindgren to discuss the project and obtain her blessing (aka, the series’ rights). While in Lindgren’s home country, Miyazaki and Takahata scouted locations and drew inspiration from Sweden’s majestic atmosphere and picturesque vistas, incorporating this into the storyboards.

However, once the duo reached Stockholm for their scheduled meeting, they learned Lindgren “could not see them.” There was no opportunity to pitch their ideas and show Lindgren their art, or demonstrate their obvious passion for the project. And without that chance, Miyazaki and Takahata’s Pippi Longstocking film was dead in the water. As the character’s creator and overseer, nothing could happen without Lindgren’s permission.

Pippi Longstocking Continued to Influence Miyazaki’s Career

To say the animators were disheartened seems an understatement. Astrid Lindgren’s website/The Phantom Pippi Longstocking quotes Miyazaki as stating at a later date, “We invested an enormous amount of energy in doing what we were planning to do. It depleted me, so now I no longer want to do it. That’s just how it goes. You cannot succeed in animation if you don’t devote everything you’ve got to it.”

Miyazaki blamed their meeting’s failure on their intermediary Beta Film, but also acknowledged his and Takahata’s lack of notoriety might have biased Lindgren against the project. He seemed to understand and sympathize with Lindgren’s point of view. As previously stated, Studio Ghibli didn’t exist yet, and although Miyazaki and Takahata had years of experience in the anime medium, they were far from the recognized worldwide names they would become thanks to critical and commercial hits like My Neighbor Totoro and Grave of the Fireflies, respectively. “It was pretty obvious,” Miyazaki said. “You don’t just meet with someone who suddenly turns up from somewhere in Asia and says ‘I want to turn your book into an animation’.”

Any animated adaptation might have been a lost cause regardless of who approached Lindgren, credentials or not. The author was “fundamentally against” Pippi Longstocking making her way to film or television screens in animated form. Various live-action adaptations were made starting as early as 1949, but it took decades for Lindgren to allow anyone to try their hands at animation. Svensk Filmindustri, a joint Canadian-German-Swedish animation studio, produced the 1997 film Pippi Longstocking followed by a television series that ran for two seasons and 26 total episodes. According to Lindgren’s website, “she wasn’t particularly happy with the result.” As of this writing, any reasons Lindgren might have cited for her critique and earlier reluctance are unclear, as is whether she denied Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata outright or simply refused to see them.

Although Miyazaki never got to pursue the project that dominated much of his passion in the 1970s, elements of Pippi Longstocking and her inspiration live on through his and Takahata’s finished works. The protagonist of the Takahata-directed Panda! Go, Panda! short film sports two red braids much like Pippi. Miyazaki modeled the Koriko town from Kiki’s Delivery Service after Gotland, the largest island in Swedish territory. Looking back at the Pippi concept art, Miyazaki’s style is readily apparent and lovingly rendered. Such a heroine would have slotted right in with Miyazaki’s personal creations. Alas, such a combination wasn’t meant to be, but there’s no doubt Pippi Longstocking continued to influence one of film’s greatest directors in subtle, but telling, ways.

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)