[ad_1]

Being founded on a cartoon mouse doesn’t destine a film studio to focus on animals, but Disney has always been happy to turn to the natural world for subject matter. Mickey Mouse was succeeded by more realistically animated critters in the Silly Symphonies series and in films like Bambi and One Hundred and One Dalmatians. These days, as majority owner of National Geographic, Disney broadcasts plenty of documentary material beyond what it produces under its Disneynature label. They have healthy competition in that field from the likes of Discovery, Apple+, and the BBC. All these modern efforts are part of a tradition largely established by Walt Disney himself through his own nature films: the True-Life Adventures series.

The documentary film as a genre predates Walt, of course, and such early pioneers as Robert Flaherty touched on natural subjects in their work. But what the True-Life series did was to popularize the idea of nonfiction movies devoted entirely to the animal kingdom that could serve as entertainment and education in equal measure. Across seven two-reel shorts and seven films released over twelve years, the series brought eight Oscars to the studio. It helped inspire a generation to take an interest in animals and won praise from naturalists – as well as a few sharp rebukes, deserved and undeserved in turns.

Making Nature Documentaries Was Original an Act of Desperation

At the beginning, however, making a film of any length about animals was an act of desperation. The 1940s were grim years for Walt Disney Productions and for Walt personally. World War II, a string of expensive underperformers at the box office, and the bad feelings caused by an animators’ strike all put severe limits on what the studio could produce. Many a passion project of Walt’s foundered from the lack of manpower and resources. The package features that kept the lights on didn’t excite Walt the way Snow White or Fantasia had. He needed something new to get his hands into, and the studio needed to diversify if it were to survive.

The industrial and educational material Disney produced for the war effort was briefly considered as a viable peacetime option, but Walt wanted to stick to entertainment (his biographer Bob Thomas reported that he ended a meeting on an industrial short with an order to return the money to clients who would no longer be getting a film). The studio slowly eased into live-action filmmaking but ramping up production in that area faced comparable limits as animation. Seemingly on a whim, Walt hired the husband/wife team of Alfred and Elma Milotte to head north to Alaska in 1947. The Milottes had experience shooting footage for travelogues, and Walt thought a film might be gleaned from what he called “our last frontier.”

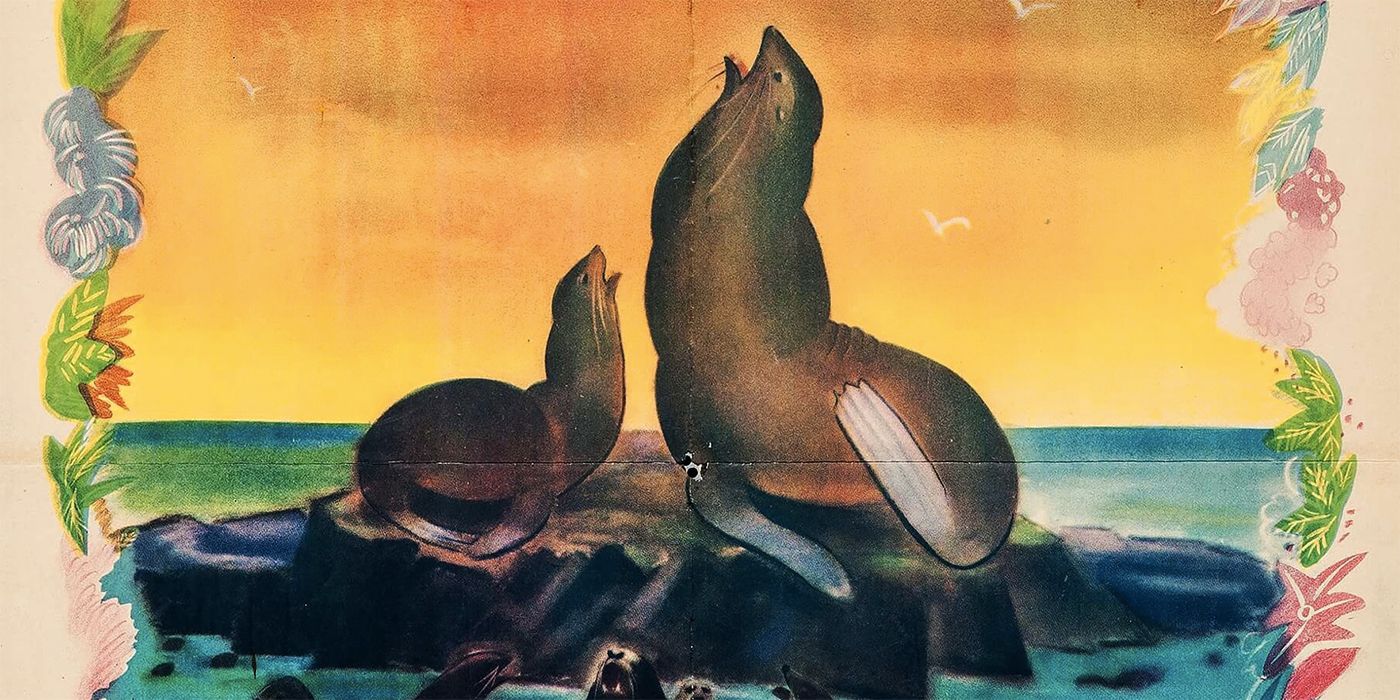

The filming expedition went on for over a year. Reams of 16mm footage came back to Burbank from Alaska, for classification by subject. No one, even Walt himself, knew at first what he was going to do with all that material. The Milottes had been directed to observe the seasonal customs of the native inhabitants, but it didn’t take Walt’s fancy. What did take his fancy was a sequence shot off the Pribilof Islands of fur seals. Walt assigned director James Algar and producer Ben Sharpsteen to make something of the footage, with the order to avoid any shots of human beings. The life cycle of the seals would dictate the story. Along with the concept, Walt provided the title. “It’s about seals on an island, so why don’t we call it ‘Seal Island’?“

“Seal Island” Launched a Bunch of New Documentaries

As the inaugural effort in the True-Life Adventures series (a series announced before Walt had any follow-up subjects in mind), “Seal Island” established the template that its successors, and so many popular nature documentaries since closely followed: a narrator and a full musical score provide a solid framework to guide viewers through wildlife footage. Flourishes unique to the True-Life series include the magic animated paintbrush that begins each film with illustration before transitioning into reality. Winston Hibler takes a jovial and slightly detached approach to deliver the narration, largely written by Algar and which tends toward the cheerful. A careful study of the editing suggests a good deal of effort went into splicing bits and pieces to fit the narration rather than the other way around, and human customs and attitudes are often relied on as illustrative aides. But nothing described in the story is implausible, and most of it corresponds to the real behavior of fur seals.

Walt was charmed by the results, but he had a hard time charming anyone else. Big brother and business partner Roy Disney worried about the costs; $100,000 wasn’t exorbitant, but they were still in lean times. Distributor RKO saw no prospects for selling a half-hour short on seals. When faced with such reluctance in the past, Walt had gone straight to the audience; he did so with “Seal Island,” arranging for it to accompany a feature film at a Los Angeles theater in December 1948. This qualified the film for an Academy Award nomination for best two-reel documentary, which it won. The day after the ceremony, Walt took the Oscar to Roy and told him: “Take this over to RKO and bang them over the head with it.” I doubt Roy followed through in the literal sense, but RKO did give “Seal Island” a wide release, and the True-Life series launched in earnest.

From seals, the series explored the lives of beavers, elk, birds, bears, lions, and jaguars, with a few entries given over to whole ecosystems or natural cycles. The True-Lifes produced after 1948 were paired with Disney features until they graduated to feature-length themselves with The Living Desert in 1953 (and became the last straw for Roy Disney in dealing with RKO; The Living Desert was the first film Disney distributed themselves through Buena Vista). The Milottes and various other camera teams spent months or even years in the wild on lean, dangerous expeditions, gathering footage for Alagar, Sharpsteen, and Walt. Low budgets and high ticket sales made the True-Life series among Disney’s most profitable, and even before it wrapped up in 1960 Walt launched the spin-off True Life Fantasy series, using wildlife footage to tell fictitious stories.

The Evolution of ‘True-Life Adventures’ to Fantasy Made Sense For Disney

That evolution was perhaps inevitable. Critics and Disney’s own marketing made a connection between the True-Life Adventures and Disney’s reputation for fantasy. One tagline boasted of stories, “strange as fantasy yet straight from the realm of fact.” For Walt, the series was a work of mass entertainment just like the rest of his films, so such framing was more appropriate than presenting them as purely educational pieces. In The Animated Man, biographer Michael Barrier quoted Algar lamenting, “Too many so-called educational films fall under the supervision of people who know their subject thoroughly but their medium very little…sadly enough, the thing turns out dull and fails of its purpose. One of the first lessons of filmmaking in the entertainment field is this: you must win your audience.”

And yet the True-Life Adventures were also presented, and taken, as an unvarnished look into the animal kingdom. The title card at the beginning of each film initially read: “These films are photographed in their natural settings and are completely authentic, unstaged, and unrehearsed.” Footage from them was repurposed into straight educational films for schools or used in the Disneyland anthology series for nonfiction segments. These pretenses to authenticity opened the series up to criticism. The editing and narration that anthropomorphized their subjects was a layer of artifice immediately evident. Shot with lightweight 16mm cameras without sound equipment, the True-Life footage needed its soundtracks built-in post, and most of the animal noises came from a sound technician and Walt’s successor as Mickey Mouse, Jimmy MacDonald. The musical scores for the films were aggressive in setting a particular tone. And contrary to the title card’s claims, some sequences of the series were deliberately staged.

Camera teams like the Milottes did gather authentic material, but in assembling stories out of it, Algar and his team often found themselves with gaps; a point about animal behavior they wished to present couldn’t be with the film available, or Walt would get an idea about one of the animals he wanted to build on. He, Algar, and many of their photographers believed that animals had definite personalities that could be exploited for entertainment, and if an animal observed in the wild showed a certain attitude that expressed a certain behavior, they saw no harm in arranging for pick-up shots with a stand-in. Photographer and animal trainer Lloyd Beebe often provided tamed critters for such shots.

‘True-Life Adventures’ Still Had a Problematic and Inhumane Side

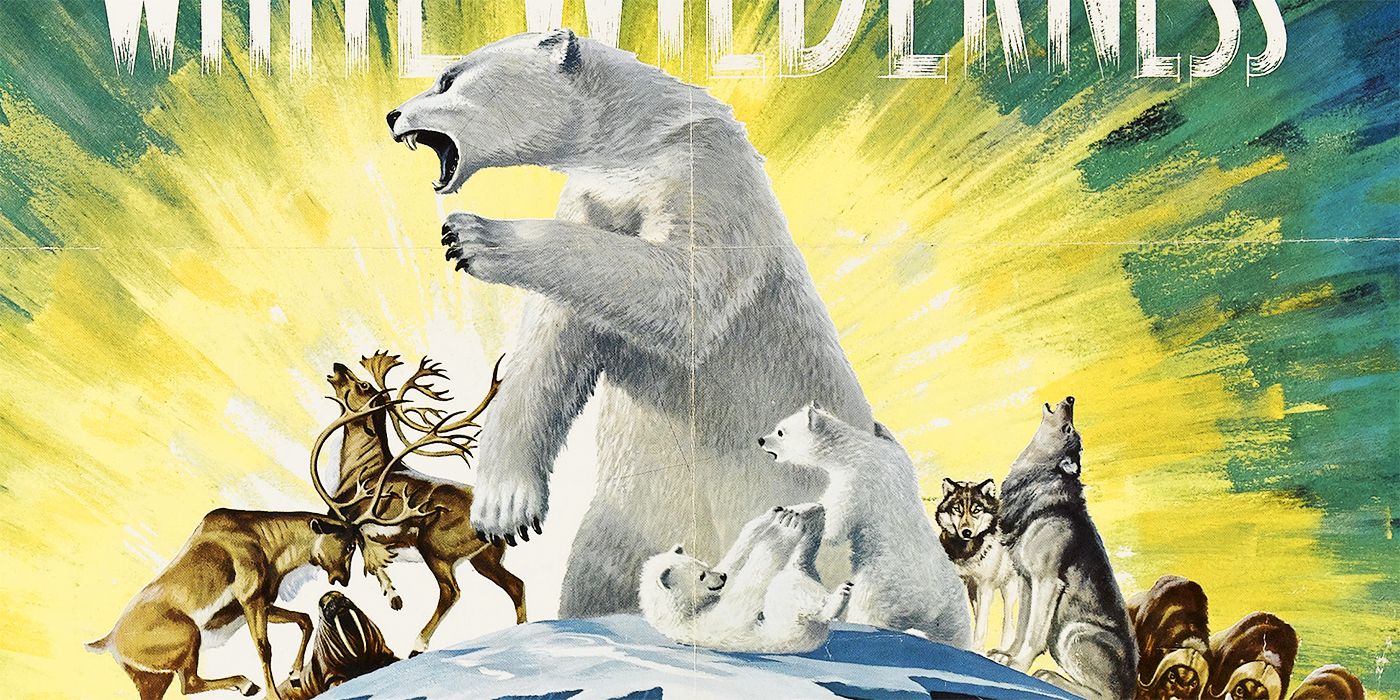

Other staged businesses came through less humane tactics. The 1958 feature White Wilderness touches on the myth of lemmings committing mass suicide, presenting it as a case of the animals mistaking the ocean for rivers during migration and drowning from exhaustion. There was no footage of this because even that supposed kernel of truth isn’t natural lemming behavior. The wildlife film was gathered in Alberta, not a native habitat for lemmings, and not connected to the ocean. Photographer James R. Simon imported a few dozen lemmings to the location, set them on turntables, and herded them off a cliff into the Bow River to get the shots needed. (The Walt Disney Family Museum maintains this was done without knowledge or approval by Walt or the studio).

That extreme case aside, Disney’s staging and other flourishes for the sake of entertainment weren’t universally condemned. In the book Reel Nature, Professor Gregg Mitman quoted the ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy defending the True-Life series over a bit of staged business concerning a Clark’s Nutcracker in 1953’s “Bear Country”. Disney got a shot of the bird catching a mouse through a tame specimen, but since the Nutcracker does regularly eat mice as part of its diet, there was “little, if any affront to the literal truth” in Murphy’s eyes. Many of Walt’s photographers felt the same way. And Mitman notes an attitude among many conservationists of the 1950s who looked upon the wilderness as a place for celebrating “frontier values” before any dry scientific considerations.

Conservation’s focus has shifted with time, deliberate staging would be more of a scandal now for a documentary, and the current generation of nature programs aren’t often so geared toward a particular tone by the music and style of narration. Yet David Attenborough’s no stranger to drawing parallels between animal behavior and our own, and you won’t find many nature shows on TV or in cinemas without some musical accompaniment. These practices from the True-Life Adventures have continued to this day, as has trying to pair education and entertainment. If the balance between the two is sometimes better calibrated in nature documentaries now, they play to a wide audience thanks to the efforts of Walt and the True-Life series that made them popular in the first place.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link