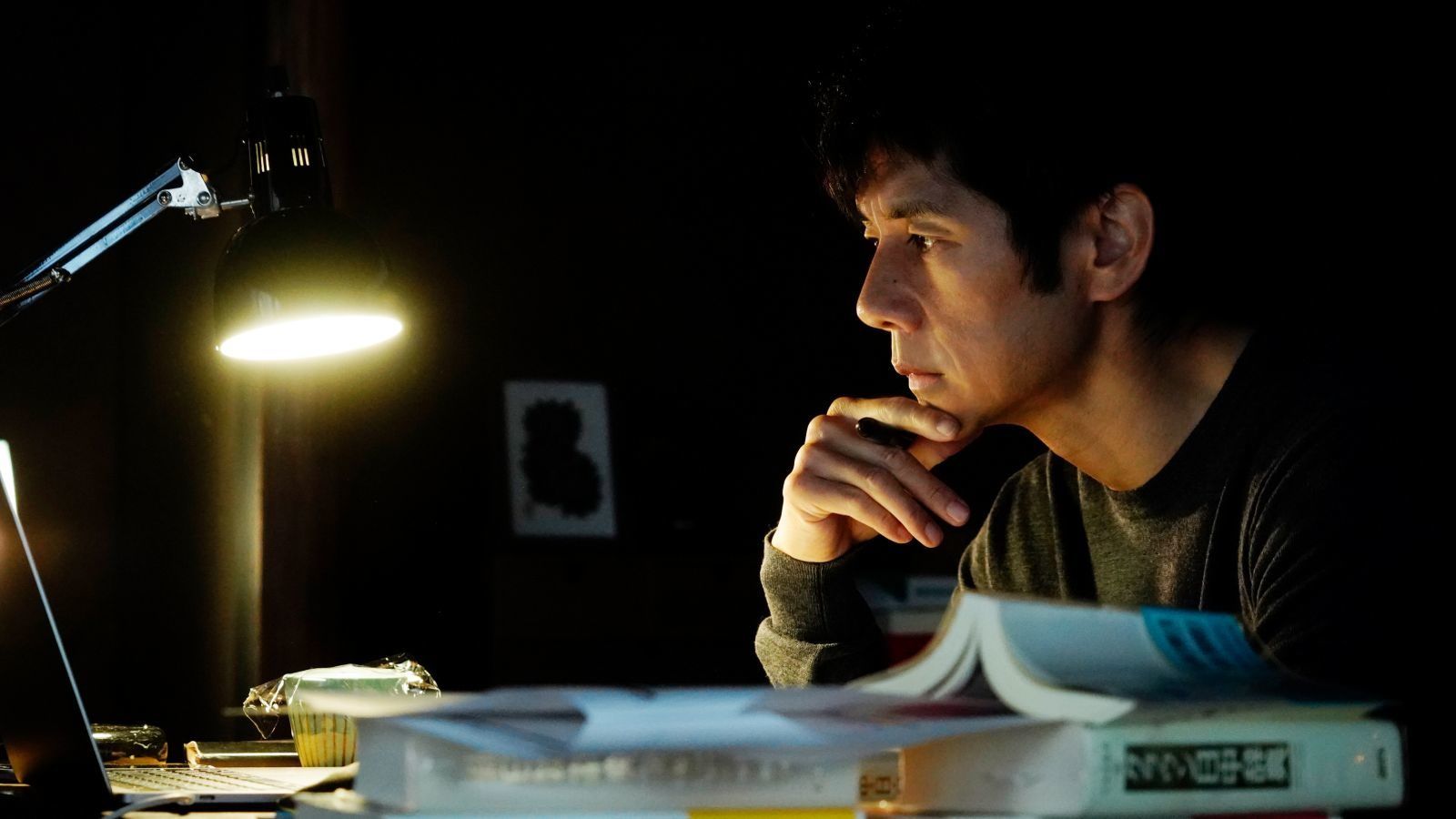

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” This may very well be the most recognizable quote from William Shakespeare’s As You Like It. Life often emulates the dynamics of theatre, and vice-versa. They are like two mirrors facing one another, no longer allowing for the distinction of which image is more real. Like Shakespeare centuries before him, Ryûsuke Hamaguchi demonstrates through his work the connection between life on and off the stage, going beyond what meets the eye and tapping into the subtle but effective power of subtext. There’s no more poignant exploration of this relation in the director’s work than his nearly three-hour-long screen adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s short story. Drive My Car is a film that understands the theatricality of social life with its texts as well as with its silences, loading both what is said and unsaid with as much meaning. It comprehends that what one person chooses to reveal is as significant as what they choose to hide. Action is not limited to outward activity, it can also exist within, unnoticeable to those who are not paying attention.

The intertextuality in Drive My Car is present explicitly through Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot and even further explored through Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, which plays a major role in the story. It’s chiefly in the juxtaposition of the playwrights’ scripts and the characters’ private and often unspoken inner lives that the movie acquires its full meaning.

Drive My Car is concerned with how people relate to one another on and off-stage, making it perfectly clear that acting does not only take place under the spotlight and in front of an audience. The protagonist, Yusuke Kafuku (Hidetoshi Nishikima), and his wife Oto (Reika Kirishima) are our first example of this. Although one’s a working actor and the other has retired from the profession, in both their cases their acting extends to their private lives. Note however that we mustn’t understand “acting” as being altogether synonymous with “lying.” While the latter can be hollow and superficial, there’s still truth in the former, even if one is not saying words that accurately represent reality. Acting can take place every single day of our lives and it is so intrinsic to our being that we may have a hard time distinguishing it ourselves. Hamaguchi understands that all human beings are “players” in their own lives as they change and adapt according to the circumstances and the people they interact with.

From early on in the film, Yusuke is playing a role that has nothing to do with his theatre productions: he acts as the husband unsuspecting of his wife’s infidelity. He represses his emotions, his hurt and sorrow, for the sake of upholding the status quo of their marriage — until he walks in on Oto having sex with a younger actor named Koshi Takatsuki (Masaki Okada). Although Oto also acts as if nothing changed, she is the one who takes the first step to drop the act and come clean. However, the day it seemed his wife would confront him with this revelation, she dies, thus forcefully breaking the cycle and depriving Yusuke of closure. No longer is he “waiting for Godot” as “Godot” is now dead and there’s nobody to wait for.

Until the end, Yusuke never found it within himself to confront Oto about her unfaithfulness. The day we can assume they are finally going to talk about it, Yusuke drives around in his car, stalling his return home and listening to the recording of Oto reading Uncle Vanya. Yusuke may want to keep up the act so that the dynamic of his marriage does not have to suffer change, but Chekhov’s text does not let him off the hook so easily: “Because that woman’s fidelity is a lie through and through. There’s an abundance of rhetoric but no logic in it.” Yusuke rehearses inside his car: “My life is lost, there’s no turning back. That thought haunts me like an evil spirit day and night. My past went by without event. It’s unimportant. But the present is worse. What should I do about my life and my love?” Although he sounds nearly devoid of emotion, we understand that underneath the surface, a tempest rages on. The Russian playwright’s text reverberates its meaningful echo in Yusuke’s private life, challenging him to liberate the feelings and thoughts he has tried to stifle.

Oto’s story about the high schooler who breaks into her crush’s house acquires additional meaning with a second viewing as we begin distinguishing the extra layer of meaning that must be inferred. Through her story, and especially through its ending, which Takatsuki recounts to Yusuke, we can start to see what lay beneath Oto’s act and what she may have wanted to tell her husband the day she died. In Takatsuki’s version, the high school girl kills a burglar who tried to take advantage of her, leaving his corpse behind. The girl knows that there’s no turning back, and she needs to confess what she has done. However, when she gets to school the next day, everyone is acting as if nothing happened, the same as Yusuke did after witnessing his wife and Takatsuki. Both Oto and the girl know they have done something reprehensible, have been caught for it, and yet, contrary to the natural order of things, the world remains unchanged. In the end, the high schooler turns to the surveillance camera, “The only change she has elicited in the world”, and admits to killing the man. “I killed him,” the girl says, mirroring how Oto was metaphorically killing Yusuke. The girl’s admission of guilt is a reflection of how Oto had grown to feel about her infidelities, to the point where she could no longer endure the apparent undisturbed normalcy. It is not outlandish to think Oto knew Yusuke had become aware of her cheating. The more we know a person, the better we can differentiate the real from the act, even if we can never truly peer into their heart.

This is a prime example of how Drive My Car uses rich subtext to get to the characters’ innermost truths. But arguably, subtext shines the most in the movie’s intertextuality, specifically through Chekhov. Two years after Oto’s passing, Yusuke shuns the role of Vanya, as the play’s focus on themes like hopelessness and the surfacing of a disconcerting past hit far too close to home. The line between reality and act becomes too blurry, and thus, he passes on the responsibility of the main role to Takatsuki. This decision is purposeful, as purposeful as Hamlet choosing “The Mousetrap” to “catch the conscience of the king.” As Yusuke expresses to Takatsuki while they are having drinks at a bar: “Chekhov is terrifying. When you say his lines, it drags out the real you.” The decision is impelled by the necessity of unmasking his wife’s lover, and Chekhov is but a vehicle to do so.

In Drive My Car, the play’s dialogue discards the emotional repression of their regular day-to-day and provides the characters with an indirect expression of their inner lives. But as the text is endowed with meaning far deeper than first meets the eye, likewise, the silences can be as meaningful. Quoting Victor Turner’s From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play: “Social life, then, even its apparently quietest moments, is characteristically ‘pregnant’ with social dramas.” It is not far-fetched to assume that playing the role of Vanya made Takatsuki more sensitized to Yusuke’s circumstances. When Takatsuki is taken from rehearsal by police for having beaten up and killed a man, he does not say anything to Yusuke, he simply bows, showing his genuine respect to the man he had previously caused so much pain. Those who don’t know the full story behind the two actors’ connection cannot perceive just how packed with meaning this gesture is.

So, besides acting, which is more pervasive than one might think, how do people relate to one another? If we were to boil it down to its fundamentals, the easiest answer may seem to be “language,” but that’s not fully accurate. Communication can create a bridge between individuals, but only when there is the willingness to connect. In his adaptation of Murakami’s work, Hamaguchi makes it clear that communication is not a feature that only belongs to those who share a language, or those who can speak at all. In fact, being able to speak the same language does not mean that one is able to properly communicate, even if one is, for instance, married for over 20 years. The fact that Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya is done in multiple languages in the movie, although it challenges communication, does not impede it. Thus proving that the ability to communicate is not so much dependent on the language as it is on the willingness to connect, to open the door and allow for vulnerability to enter.

Without connection, communication is rendered ineffective. This works in real life just as much as on the stage. When sharing the stage with another actor, one cannot limit themselves to saying the memorized lines; there must be co-acting, respect and awareness of the others who share the same stage. It’s through sharing a scene, co-acting with another, that one can have a better grasp of one’s own inner life and reach an emotional catharsis. This is what happens on and off the stage in Drive My Car. Thus, the movie provides a thoughtful reflection on the Hegelian principle that it is only through the encounter with another that we can know ourselves and attain satisfaction. The ability to communicate is not so much dependent on the language spoken as it is on the willingness to connect, to share the stage and the scene.

We dive into dangerous waters when the act takes over our lives to the point where we become detached from the self and unable to articulate our innermost truths. Such is Yusuke’s case until he finds a moment of catharsis, of emotional release and confession of deep-seated pain, thanks to his newfound connection with his driver Misaki Watari (Toko Miura). The healing process can finally begin when one drops the pretense, forsakes the mask, leaves out the pre-written dialogue and truly starts communicating.

Catharsis in the film finds its best expression in Sonya’s monologue at the end of Uncle Vanya, powerfully done in sign language. However, contrary to its message, Drive My Car proves that we need not wait for the afterlife to reveal to God our suffering and pain, instead, we can choose to do it in life. We can choose to be open to connection and allow ourselves to be driven by another when we lack the capacity to take the wheel ourselves. We are all actors in this world that is a stage, and as such, we must inevitably share a scene, and we can only make the most out of it when we allow ourselves to connect. Backed up by connection, unfiltered communication forms a bridge when it may feel like there’s nowhere to go. Finally, through art, both the audience and the artist can find the necessary path to the catharsis real life sometimes denies.

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)