By the mid-1990s, Dana Carvey was a household name. After a seven-year stint on Saturday Night Live and starring roles in a handful of films, he’d firmly established himself as a premiere voice in entertainment. His next career move, a self-titled variety show featuring early work from several then-unknown talents, proved to be a bold venture that swung for the fences and painted with broad comedic strokes. But shortly after debuting in March 1996, The Dana Carvey Show vanished from television screens after a mere seven episodes. With material ranging from surreal to crude and absurdist to raunchy, the series polarized viewers, ultimately leaving behind a legacy as one of the most experimental exercises of its time, and serving as a launching pad for future A-listers.

How Did ‘The Dana Carvey Show’ Happen?

After departing Saturday Night Live in 1993, Dana Carvey was in high demand. Having received numerous offers, including a late-night talk show gig replacing David Letterman, the 40-year-old was operating with significant creative leverage. But rather than take on a talk show, Carvey had his eyes on another prize. After teaming up with famed SNL writer Robert Smigel, the decision to pursue a variety show was made in 1995. Smigel remembers, “I chose to work with Dana because I was excited to try and reinvent the format with him rather than rebuild something that was already established.”

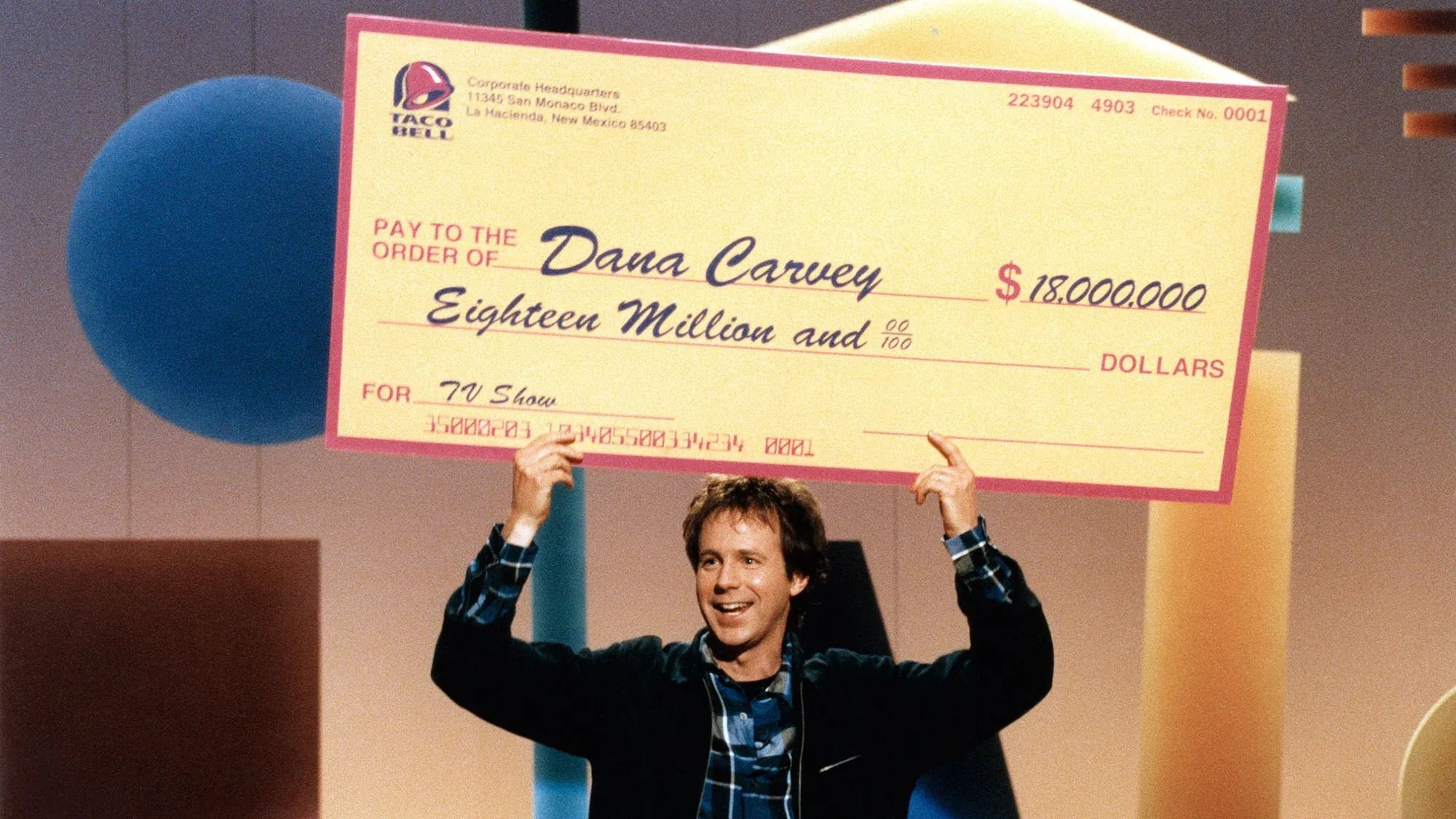

With a format in mind, the duo began shopping their idea around town. One of the most consequential decisions to make was which network to take the series to. Carvey wanted it to go to HBO, presumably so he and his collaborators could explore more edgy material unsuitable for network television. But at the insistence of others, it landed a primetime slot at ABC. Carvey’s said of the decision, “Once we made that choice, our fate was sealed in not being a long-running show. I think that ABC sincerely wooed us and threw lots of money at us.” For better or worse, and despite the show’s final destination, its performers and writers wouldn’t hold back in crafting content that defied the sensibilities of mainstream comedic entertainment in the ’90s.

Who Worked on ‘The Dana Carvey Show’?

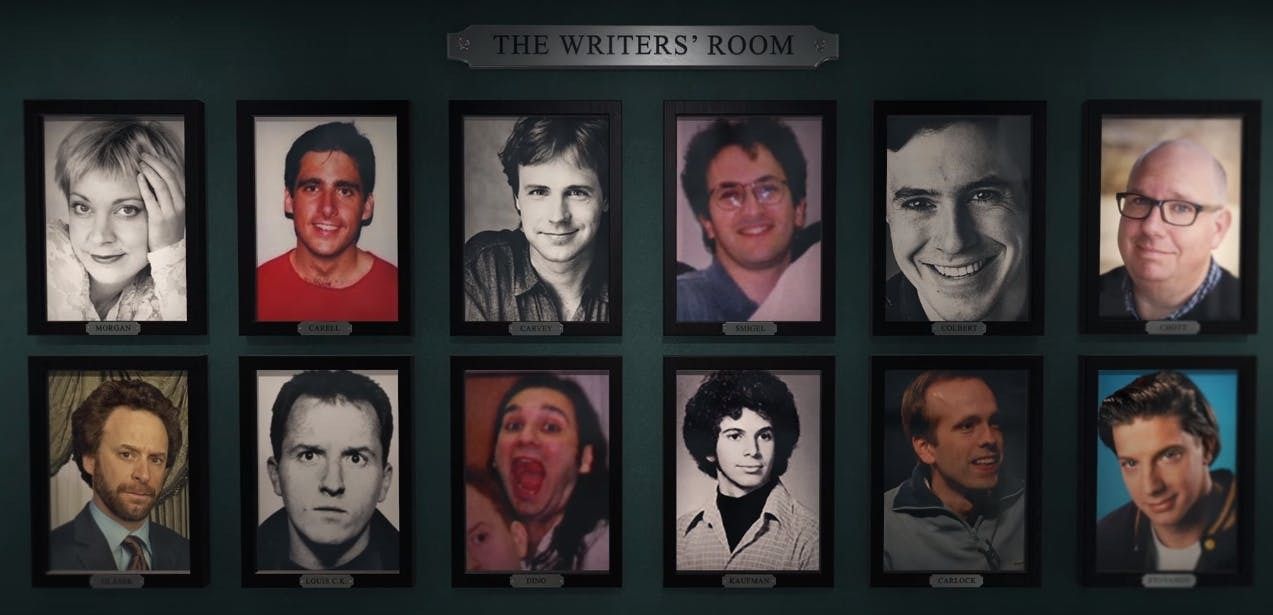

Having secured studio space at the CBS Broadcast Center in Manhattan, the search for talent began. While SNL, which was in the process of revamping its cast, had the pick of the litter with hopeful comics in New York City, the sketch comedy giant shared leftover video auditions with Carvey, Smigel, and head writer Louis C.K. Two future players on The Dana Carvey Show would be hired based on their SNL auditions: Bill Chott and Jon Glaser. Also joining the cast were Heather Morgan (the main cast’s lone female) and Elon Gold, among others. Smigel’s been up front about the talent that might have slipped through their fingers. “I’ve got to admit that we did pass on Jimmy Fallon, Ana Gasteyer, Tracy Morgan, and some others.” Those three were among some of the actors who auditioned and were rejected.

But the two stand out players of the show were unknown comedians Stephen Colbert and Steve Carell. The former was spotted while performing with The Second City as the latter’s understudy. After unsuccessful bids to work for Lorne Michaels and Conan O’Brien, Colbert remained in Robert Smigel’s memory and was given a chance to audition based on a decidedly awkward tape he’d sent to the New York offices. Colbert remembers, “I held up my daughter in front of the camera and did a monologue as my daughter, and I did my voice through the baby.” Steve Carell was also allowed to audition, and both comedians ultimately made the cut after a final round in Los Angeles.

Rounding out the show’s writer’s room were Dino Stamatopolous, Robert Carlock, Greg Daniels, Bob Odenkirk, and future Oscar-winner Charlie Kaufman. Kaufman quickly developed a reputation among colleagues as a quiet, introverted, yet brilliant writer. Jon Glaser remembers, “I remember, I think he was just talking about Being John Malkovich, and I think it was just starting to make a little headway.” Steve Carrell also sang Kaufman’s praises. “Who knew that way back then the quiet guy at the end of the hall was going to become the mad genius of cinema?”

In the Wrong Place at the Wrong Time

Even before The Dana Carvey Show aired, and despite the excitement of working on a new primetime variety series, there was a palpable level of uneasiness regarding its slot on a mainstream TV network. The Disney-owned ABC featured a great deal of family-friendly programming, as was evidenced by a two-page spread in People magazine in anticipation of the season’s upcoming shows. In a quintessential example of an apples-to-oranges comparison, at the center of the fold were Dana Carvey and Kermit the Frog.

The ad in People sent shock waves of dread through the cast and creative team, Jon Glaser remembers, “There was definitely a sense early on, hanging out, thinking, ‘Yep, this isn’t going anywhere.’ It was a huge bummer of a photo.” Colbert echoed the sentiment with, “We were screwed from both directions. Dana said to me, ‘I’m so sorry, you guys. I’ve ruined your careers.'” And it was before the show ever went on the air.

To further complicate the matter was the fact that The Dana Carvey Show was scheduled to follow Home Improvement. At first glance, one would expect having one of television’s most popular shows as a lead-in to be a thrilling prospect in terms of exposure and ratings, but the obvious tonal contrast between the two shows had people justifiably anxious. Upon seeing Home Improvement for the first time, Robert Smigel gave it a look and “just watched in horror–not believing what we had foisted on this audience. I thought about what we had put on television, following this family-oriented show that I now realized was successful because kids and parents could watch it together.”

The Show Gets Off to a Rocky Start

On March 12, 1996, The Dana Carvey Show premiered on ABC. The pilot’s first sketch featured Carvey as Bill Clinton riffing on the upcoming Presidential election. Much like an SNL cold open in its first minutes, everything seemed just fine and dandy. But suddenly, the notion of being a “caring and nurturing president” takes a turn for the bizarre when Clinton reveals he can breastfeed. Seconds later, after opening his shirt and revealing multiple additional nipples, the President begins breastfeeding babies and puppies.

At this moment, minutes into a brand new primetime series, the proverbial nail was put in the coffin, sealing The Dana Carvey Show‘s fate. Writer Robert Carlock said of the sketch, “ABC paid Nielsen extra to get a rating graph broken down minute by minute. At around that two-minute mark when the breast came out, like six million people changed the channel. It was kind of remarkable that we made that many people do something all at the same time.” Robert Smigel bluntly said of the series premiere, “We literally killed our show in the first five minutes.”

In addition to immediately losing millions of viewers in minutes, The Dana Carvey Show and its off-color, edgy material also rubbed its sponsors the wrong way. With major brands like Mountain Dew, Taco Bell, and Pepsi initially attaching their names, several of them promptly dropped the series. By the time the sixth episode aired, the show was sponsored by Szechuan Dynasty, a local Chinese restaurant in Manhattan.

Despite Its Often Bizarre Nature, ‘The Dana Carvey Show’ Featured Hilarious Content

Wholly aware that their new show was off to a rocky start and likely wouldn’t get picked up, the cast and writers pushed forward with admirable commitment to their unorthodox material. While leading the series with a sketch of America’s president breastfeeding babies and puppies was certainly a risky move, The Dana Carvey Show featured many sketches that worked to great comedic effect. Elon Gold nailed idiosyncratic impressions of celebrities like Howard Stern, Jeff Goldblum, Gene Wilder, and David Schwimmer. Stephen Colbert and Steve Carell brought sidesplitting laughs with bits like “Waiters Who Are Nauseated by Food” and Germans Who Say Nice Things.” Heather Morgan went out on a hilarious limb with “First Ladies as Dogs” and “Overly Anxious Dinner Conversation.” And Robert Smigel’s famous animated sketch, “The Ambiguously Gay Duo,” would ultimately find a home at SNL after debuting on the series’ brief run.

A Bold Show Ahead of Its Time

The Dana Carvey Show aired its final episode on April 30, 1996, less than two months after premiering. Among its cast and writers, the reaction to the cancelation was not one of surprise. Jon Glaser remembers, “it never affected the mood of anybody enough where people were walking around moping. To me, the whole experience was mostly just really fun.” But to add insult to injury, not only was the show canned, its eighth and final episode was never broadcast. Carvey has since said of the cancelation, “It became very clear to me after the Clinton teat that the network had lost interest. Our ratings had gone down to what would now be a number one show.”

While it seemingly came and went with a whimper, The Dana Carvey Show remains a gold mine of bold, surreal, and creative comedy. Rather than play it safe with a focus on light and topical material, the short-lived variety show, consciously or not, set itself apart from the mainstream while situated smack dab in such an environment on network television. Carvey acknowledged, “When you put Steve Carell, Smigel, Colbert, Louis C.K., and Charlie Kaufman together and doing what we wanted—it does make sense that it was just in the wrong spot. But I’m still really proud of it. I think it’s one of the most abstract variety shows to ever have been on primetime television. You were working on ideas that were so fucking funny. It’s very rare.”

Despite the show’s short-lived run and relegation to cultural obscurity, The Dana Carvey Show nonetheless found a place in the lexicon of American entertainment. Introducing future powerhouse talents and amassing a cult following over time, as well as being the subject of the 2017 documentary Too Funny To Fail, the variety series was an early indicator of the kind of experimental, surreal comedic content that would eventually become commonplace outside of network television.

![Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic] Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/9e7sW3TubFHM00yvXe5zvvbhAVriJiGqS8xmVFLPC6s/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zb2NpYWxfc3ByaW5nX2NsZWFuaW5nMi5wbmc=.webp)

![5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic] 5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/Hv-m77iIkXSAtB3IEwA3XAuouMwkZApIeDGDnLy5Yhs/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9saW5rZWRpbl9zdHJhdGVneV9pbmZvMi5wbmc=.webp)