The Big Picture

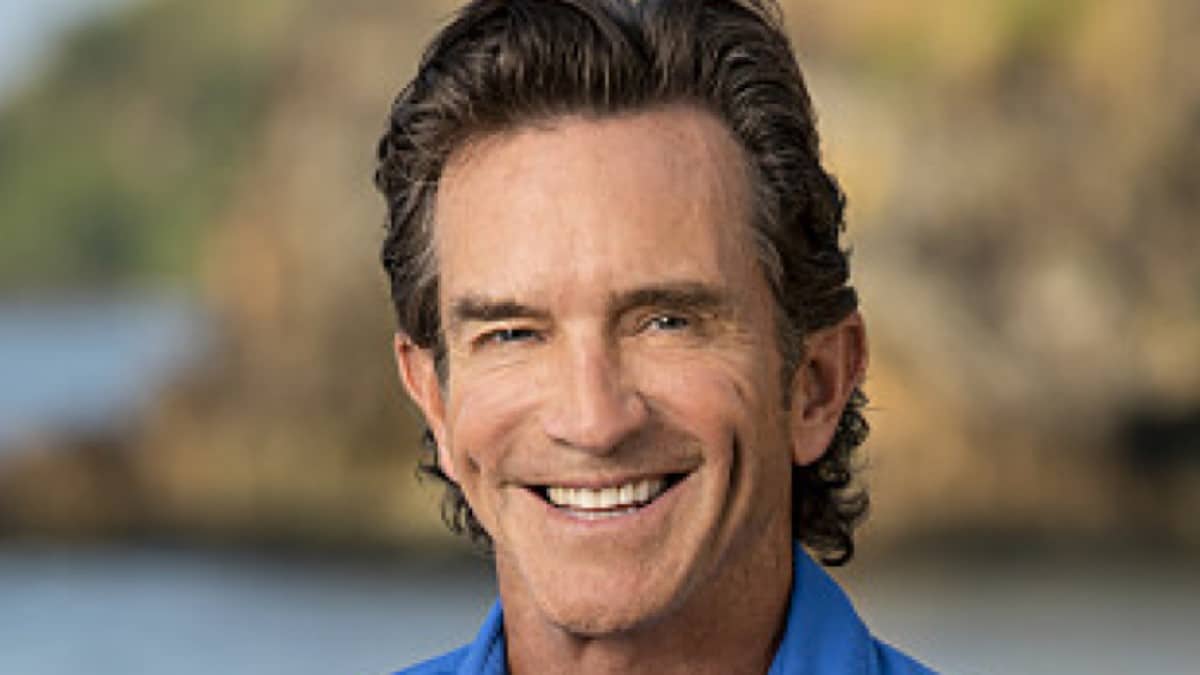

- Director Tarsem Singh discusses his long-awaited film, “Dear Jassi,” a retelling of a tragic love story, in an in-depth interview with Collider.

- Singh explains that while “Dear Jassi” is visually striking like his previous films, it deviates from his usual otherworldly style.

- Singh talks about his unique visual storytelling, his inspiration for the film, and the behind-the-scenes process of the 50-day shoot.

It’s been nearly a decade since filmmaker Tarsem Singh (The Fall) helmed a feature film. In celebration of his next full-length production, Dear Jassi, debuting at this year’s TIFF, Collider’s Steve Weintraub spoke in-depth with the director about his Romeo & Juliet-esque retelling of a tragically true love story. They discuss the inspiration behind the film as well as the making of and dig into Singh’s telltale style throughout his career.

Dear Jassi stars Pavia Sidhu (Cruel Summer) and Yugam Sood, in his first-ever onscreen role, as the two star-crossed lovers, Jassi and Mithu. Longtime fans of Singh will find the romantic drama quite unlike the striking, otherworldly stories he typically directs, like his Oscar-nominated The Cell and previous TIFF entry The Fall, starring Lee Pace, though the movie will still be just as visually striking. “You find my DNA in practically everything that I do,” Singh tells Weintraub, referring to his stylized storytelling. Written by Amit Rai, Dear Jassi is a tale Singh’s been holding close for years, and before any other future projects could be considered, he tells us he had to “get this devil off [his] back.”

During their interview, Singh takes us back to the beginning, where his path to filmmaking began. With two Oscar-nominated features out of six, a high-profile career with commercials for brands like Nike and Coca-Cola, and music videos for R.E.M., Lady Gaga, and more, Singh’s visual style is not only what he deems “very polarizing,” but impactful. He digs into why his methods are so unique, what his career has in common with Zack Snyder, what it’s like to host a private screening with David Fincher and Spike Jonze, and if we’ll ever get a 4K re-release for The Fall. Of Dear Jassi, Singh explains why this story had to be made now, what about the true story it’s based on he changed, and the behind-the-scenes of their rapid, 50-day shoot. For all of this and more, check out the full interview below.

COLLIDER: What do fans need to do to get The Fall on 4K Ultra HD?

TARSEM SINGH: I will solve that within two weeks of TIFF. I’ve finally decided that at this current time, it’s been waiting for long enough. We’ll try to find an outlet for it because everybody tells me that to see it, it costs like $300 on a Blu-ray and blah, blah, blah, and not good quality. I swear to you, I’ll follow that up maybe by TIFF, but hopefully a week after TIFF, all my attention will go to that. I’ll get it done.

That seems to me like the perfect Criterion release. Have you thought about going to them?

SINGH: We have. It was the strangest thing, they kind of have not responded to it. The kind of stuff that I like, it’s that kind of a film. It’s very polarizing. People think it’s the best thing, or they think it’s the biggest piece of shit in the world, and both are okay with me…Somehow, in this particular one, whenever we’ve approached everybody– I did tell the lawyer and everything after this particular one, “I will have a chat, and we’ll find an outlet for it.” But Criterion doesn’t seem to think it’s their kind of film, which is bizarre.

That doesn’t make any sense to me in any way, shape, or form, but I’m happy that you’re going to be pursuing a 4K release.

SINGH: I’m trying really hard. Write to Criterion and let them know. They just kind of ignored me for about a year, and I just thought, “I’ll move on because people are wanting to see it.” It’s just countries like Japan and all reach out individually and say, “Can we have it?” And we’ve been able to solve that, but right now, I’d love for it to stream in some way.

I’m definitely going to do a story with what you just said, and hopefully that will lead to somebody saying, “Hey,” and reaching out.

SINGH: Thank you.

You’ve done a number of films, so if someone has actually never seen anything you’ve done before, what is the first thing you’d like them watching and why?

SINGH: I always think The Fall because that’s the most personal film I did, and then the one I did right now is another personal film, so always these ones. But I kind of grind my teeth on learning the technology and everything through visual films, so my storytelling is very visual. It’s just that, initially, before this film, I’ve always done what I would call visual. I think that this film, Dear Jassi, is visual, but it’s a very flat film, meaning– It’s not supernatural. I’m looking for something to say that makes it the kind of film like The Cell and Immortals – a different type of visual. Jassi is one which is not spectacular, but it’s a very visual film. It’s told with practically very, very, very little coverage, and it’s just the actors performing with it. It just doesn’t have the kind of grandioseness that people look for in the kind of films that I do. So, it’s not, in that way, spectacular. So, I’d say you find my DNA in practically everything that I do. I’m kind of lucky to have been able to make films. Accepted or not, they are part of me, so I just put them out there.

I’ve never done a movie that was ever recommended by critics. This might be the first one. It took about a decade and a half and then slowly they start creeping up on the Tomatometer, but they’re very polarizing. Either people can’t stand the violence of The Cell or something, or they think it’s too graphic. I think it’s hilarious, the movie, personally, but people can’t take that. It’s kind of like an opera, but they look at that and they get so alienated from the violence that they don’t see anything through it. Then they’ll watch The Fall and the people who like The Cell seem to hate The Fall, who love The Fall seem to hate The Cell, and I go like, “Hey, they’re both mine!”

Which of your films changed the most in the editing room in ways you didn’t expect?

SINGH: None. [Laughs] Unfortunately, I’m kind of in between. I have like two friends who I think are on polar different sides of what I like – Spike Jonze and [David] Fincher. Fincher will make a movie, and be like, “This is it. You don’t like it, you’re an idiot.” Spike, on the other hand, will make a movie and he will review it 85 times, and by the end of it, he found the film he was making and it’s so Spike by the end of it, but all that testing is what it requires. For me and most of the films, I’m kind of in between. I just go like, “This is what I intended. Can you see that?” And if you can’t, I’ll just try to tweak to make you see what was intended because the culture that I tend to make the films for, I’m not from that.

I didn’t grow up in Hollywood on any of the regular films, so when I do it, I just think certain things are too obvious, and they’ll go like, “I didn’t get it at all.” And certain things I’ll say are subtle and people will go like, “That is so over-the-fucking-top,” and I’ll go, “Oh, okay.” So I have to find that mix on what they call sometimes in cinema when you review films “a funny laugh,” or a thing like that, which is like, “I’m not laughing.” “It wasn’t intended.” So I try to find those and weed those out, but that’s all I’ve ever changed in a movie. Of any of those that I’ve ended up making, I was lucky enough to make the films that I made.

If you could get the financing to make anything you want, what would you make and why?

SINGH: I don’t know if I would have such a project because I’ve tended to make what I wanted to make. The Fall came along only because I just thought it was the kind of film my friends tried forever to get me any financing for it, and then just realized it just wasn’t possible. I was literally walking around with a little box and showing people, and saying, “Hey, this is the film.” And they’d say, “Is it a script?” I’d say, “Here it is.” “Is that a script?” “No, it’s not the script. The child, when I find it, is going to write the script.” They’d were like, “Okay, then fuck off.” So it was one of those. It took a long time for me to then turn around and go like, “Oh, so this is the thing?” It kind of has to be a personal folly, otherwise it will never get made. The reason I wanted to make that was that it was kind of like a monkey sitting on my shoulder that was refusing to let me make other Hollywood films unless I got it off. It was literally an exorcism. I had to do it. I had been putting it together for 26 years. It was exactly the same time when I came across Dear Jassi, though. When I came across that story, I called my brother and I said, “We should make this movie right now or wait for at least two decades when it becomes slightly retro.” And then The Fall happened. I found the little girl and I went off on this magical mystery tour, and then I did all the films I wanted to make.

Recently I’ve been asked, “Would you like to make a movie in India? Would you like to make a Hindi movie or a Bollywood movie?” I go like, “Nah, because there’s a personal film that I want to get off my shoulder.” And the guys said, “Tell us…” I told it to them and they just said, “We are in if this world will bring you to India.” And I just said, “Okay.” They got me a guy and I told him the story in one whole thing. I said, “This is the structure I see, this is what I’ve got,” and I just thought that was the last I’ll hear from them. COVID hits, the guy went off to a hotel somewhere. I’m with [Amit] Rai, I love him, and he uses the word [for] what happened to me…I always say that I was possessed during The Fall and here I was obsessed, but I think he was possessed. He says that literally the spirit of the girl wrote it for him. He is a very spiritual guy and I’m not, I’ve been an atheist since I was an early teen. This guy went in and he just said he went into a hotel, COVID had locked everything down, and in one go, he wrote the piece. When I talked to him, I told him, “I need to take off about 30% of it. That’s exactly the movie I want to make, but I don’t care about their childhood and I don’t care about the post,” because the story went much darker later. I just said, “I’m possessed by the story I wanted to tell 20 years ago, so I want to take this part out.”

So, I just tweaked that and added a beginning and an end as a Punjabi folk teller story element. None of the people who I made the movie with were Punjabi. It’s my mother tongue; I come from that region. The girl moved to Canada about the time that I had gone to Canada, so I was very familiar with the essence of it. So it is written, then turned into Punjabi and turned into English, so there’s a lot of Chinese whisper stuff going on, but it just came together magically.

So I just don’t know if there’s a project that I would tell people I’d like to make. I just think I’m a bit lazy like that, that I live kind of a little bit– I wouldn’t say hand-to-mouth, but I live, like, ear-to-eye. I will hear something that excites me and I will go, “This is it,” and I’ll burn all bridges and it happens. So, I don’t know when that will happen. I’ll let you know immediately. There are some projects right now, but I’m not committed to them because once I commit, then you either have to commit me or I will kill somebody.

[Laughs] I understand. You’ve directed a lot of commercials; is there one or two you’re especially proud of that if someone hasn’t seen your commercials, you’d like them to watch?

SINGH: The best stuff, I always think, is my school work. It’s been downhill since. There were no clients, no nothing, I just did some of the most amazing stuff there. I just made up the products and made that up. If you’re American, I think the one that they aired during the Super Bowl worked because usually I hate voiceovers but in that one it worked very much. It’s called Upstream for Toyota, which was for the Paralympics. That doesn’t look like my style at all actually, but it is something that really stands out. I’m one of those guys that whatever he’s doing right now is the best thing since sliced bread and forget all history. So, for me, that’s the last one I did in America [laughs], so I think I do like that. But from the old days, if you’re a soccer fan, there’s something called Good vs Evil which defined all big Nike soccer ads. So I just think those two were quintessential in doing the kind of work that I do.

I want to say congrats on the movie, and I’m glad you’re telling this story. I’m curious, because this is the first time you’re making a movie based on what really happened on real people, did you apply extra pressure to yourself to tell their story as good as you could tell it because, essentially, this is how so many people are going to learn about these two individuals and what happened?

SINGH: I wish I could say, “Yes, I applied pressure,” but no. I think, for me, I really love the process of telling stories. If the end product works, it’s great, and I try to stay truthful to that as much as possible, but I have to enjoy the process. In this particular one, I keep saying the line that I always use for ad people whenever they ask me why I show so much interest, and I just go, “I am like a prostitute in love with this profession; I sleep with them for free, but they give me money.” It’s the only thing I know how to do. I’m a mess at everything else and I mean, hey, the girlfriend, wife, they’ll all tell you that. It’s true. I just can’t do anything else but tell stories.

So when I made this film, it was just something that I was obsessed with because of a particular– I mean, it’s a bit of a spoiler, but there’s a telephone call that happens in the very end and I had heard about that. The ending part was something that kind of really bothered me because the whole idea of calling it an honor killing and everything is just a bit cliche because that event does happen much more often than we’d ever like to admit. It’s a very wrong word to use for people killing their family members because they don’t agree with who they’re going to marry. If it was American, they would have renamed it as dishonor killings…and I think that’s what they should start calling it in India. But somehow they keep thinking, “Oh, there’s an alternative side.” There isn’t. It’s not your life to live if the other person decides to marry somebody else. So it was this telephone call that I had heard that the people who had got the girl made to the mother, and it just bothered me. I backtracked from that. I said, “If that is a true event, what is normal for these guys that that makes sense?” Then I worked backwards into the story. So I knew that that was going to be ending because if you to Google these guys, you’ll find that his story got a lot more horrendous after. I just felt like, “Okay, I’ll just stop right there,” because that was the thing that drove me, always, to say, “What is a story that I can make people believe that such a call happened?” And I worked backward from it.

So there was not really particularly any special pressure. I just knew that, from the art director to the DP to the writer to everybody, nobody had been to Punjab, they don’t speak Punjabi. I just knew that I know how this thing will play out. “Just be a lot more attentive to what I asked for,” and a lot of me saying, “Like this, like this, like this,” which I very rarely do. Usually our department, I’ll give them carte blanche wardrobe, I’ll give them very rough briefs, and I’ll be the editor. In this particular one, it was quite dictated. And then I just thought that I would work with people who haven’t acted before, I don’t care. It just has to be the right kind of chemistry that has to come across, which is what I did, also, when I did The Fall. I was just waiting when the girl could not understand, when she could then I shot the movie in sequence. So here, the guy had never done anything, he’s just a sportsman. So when I did that, I shot the movie in sequence just so that when they started meeting, the romance and everything, I wanted it to be as real and awkward as it would play out if there was slight language and a massive cultural barrier.

Because no one will have seen the movie yet, how have you been describing the film to friends and family?

SINGH: I’d say it’s a harsh Romeo and Juliet. [Laughs] The funny thing is, a friend of mine already pointed it out, then I started using the words Rome and Juliet a lot more on how similar the events are. If anybody asked me, “Oh, you made that up?” None of those, the whole thing about drugging the family to sleep to do that, all that actually was there. He said, “Oh, just like in Romeo and Juliet?” And I was like, “Yeah…” it literally dawned on me much, much later. So, I would say it is a Romeo and Juliet. It’s a love story that needs to be seen to be remembered.

It is pretty crazy how many similarities there are to Romeo and Juliet in the film. It’s bizarre actually.

SINGH: And you can ask me any of them and I will tell you, “Anything that you think is made up, I will guarantee you 95% is the real thing.” The only thing that I changed…I would not have been able to afford to make something look 25 years old in the locations, so I moved the locations away from exactly where the event happened…I moved it closer to the Pakistani border because there’s not been any new build-ups there and the villages still look old, so that looks like 25 years old. I couldn’t afford to spend anything on the art direction. I just left it how it was. I just moved the villages, that’s all I did.

Where they got married…the places changed so much, you wouldn’t be able to art direct it, so I moved to Chandigarh, which is the capital of Punjab, which was designed by Corbusier, and because it’s a cultural thing, you’re not allowed to build anything new in the center of that city. So I just thought, “Okay, they will go to Chandigarh for getting married so I know it’s already art directed.” It’s just for period-wise, I made that decision, it was nothing else.

One of the things that I thought that you did such a great job with was the way you depicted the act of violence, where you placed the camera. It’s hard to talk about this because it’s spoilers. Can you talk a little bit about why you wanted to photograph it that way?

SINGH: The funny thing is that came to me quite early. When you asked me, “How do I tell the story to anybody?” For film buffs, I can tell you how they’ll understand it; I say, “Imagine a script written by [Michael] Haneke or Gaspar Noé, but it gets directed by one of the Iranians.” That’s exactly the film I set out to make. Because the Iranians will make a movie about a divorce or a child not coming home from school and make it look like the end of the world because it is for those people at that particular time. Haneke can take a really harsh rape or something like that and then tell it really coldly. And I just thought, “You know what? If they had wrote a script the Iranians wouldn’t want to show it. How would he do it?” And that’s how I approached it.

So when they get in bed ready to have sex, “Next scene!” This is about to happen? “Next scene.” It is all like that. The only thing was, there was one thing that was an accident and I tried three times, and I thought, “Somebody will get hurt,” so I stopped. I did not want to show when the confrontation happens on the scooter. The scooter was supposed to go in the bushes. They just missed it three times. And knowing Indians, they get very gung-ho, and I just thought, “They’ll keep doing this stunt until somebody gets hurt,” and I said, “Stop it. It’s alright. I’ll make that visually, you’ll see it.” Otherwise, nothing else needs to be seen. And later on, I was going to go and reshoot it, and the reason I liked it is that throughout the film that thing is so jarring because whenever you expect to see the natural occurrence of it, like, “Oh, they’re kissing,” or they are about to do something, I always cut away. So when this thing happened and you go, “Oh, he’s gonna cut away,” but no, we do the worst thing possible, and you see it coldly.

Then the last scene was the only one that was on paper. I think it’s the best shot. The day I shot it, I had a little bit of a meltdown. I told everybody to take a break because we were supposed to shoot that for a long time. I prepared it for 14 days. We did it in one take, we shot one rehearsal. I shot all the guys before and everything naturally came together. I just said, “Leave it,” and that’s exactly how I planned it. There, the writer and everybody felt quite different. They just said, “You have to see,” and it was written so graphically that one of the people who I was talking to for if she wanted to play the part, people would just walk away saying, “No, that kind of stuff I don’t want to be involved with.” And I kept telling him, “You don’t want to see this.” You will be so much more disturbed if you have a banal conversation to go with the Hitchcock cliche of bomb under-the-table and banal stuff on top, as long as you can show it. But if I can show what’s happening there…it will be a lot more frustrating. And, completely until the end, the writer disagreed until I showed him the film. And I just said, “We cannot go there. You alienate the people we want to show this movie to.” And thus, I made those decisions from there. Then of course, it’s an 18-minute shot. I ended up using 16 minutes of it in the end, the last shot. But it’s very, very complicated for how simple it is.

One of the things that you do is you have a narrator book-ending the film. At the beginning, you basically have the narrator say this is not an exact story, so how did you decide on the narrator telling the audience on camera that this is not a perfectly told film?

SINGH: Damn, I wish I could not have those words be said, but I can see how that’s how it’s read. The thing of it is, when I told the story to the writer and I told him the structure that I wanted, it was a particular structure. He gave me a lot more to make sense of these guys in their childhood, and I told him no. I needed to start here, when they first meet, and end here. And he said, “But you won’t get this background or that background.” I thought about it, and I realized about seven years ago, I had seen this folk singer in a fair in India perform, and I just thought he was fucking amazing. And of course, my niece and everybody just fell in love with him, and I just said, “That guy. I will get him.”

You get this in Pakistan, Punjab and all that, but storytellers kind of come to your village, and especially the Sufis, they’ll sing a story to you. They’ll tell you the story. It’s usually their association, they consider it a religious experience, because the Sufis put love of people as equivalent to love for God. They will sing that. So their songs are full of things like, “And then Romeo said this to Juliet, oh my god!” They do it like that. They just believe that a woman in love or a man in love, truly in love, are basically the best form of a human experience that you can have, and that is God. So I just said, “I’ll get one of them,” and not one of them, I said, “This guy,” to come in and abbreviate the two ends. So you used the exact words, the bookends. I just said, “He will come in and he will tell you, and now I can remove 20 pages from the beginning because I don’t care about their childhood. He can give it to you in a nutshell.” Then in the ending, I don’t want to know what happened after. He can tell you that you see what the situation was, go ahead and just research it on the internet. He says it like that before he walks off into the sunrise.

The problem is that because I was scared that a lot of people would actually attack him for how some of the stuff I might not be able to afford on the art direction. A lot of the problem, I’m finding, has got to do with the translation because I did the subtitles myself and I wish I hadn’t. Because at that particular point, all he’s saying is, “To tell a story for four years in two hours, you know, give me a little poetic license.” But the truth is, what you’re saying is how everybody is perceiving it because a lot of people have asked me, “So what did you change?” And I go, “Practically nothing! That’s exactly how they did all these things.” I just want you to look at it and not be lost, and “Oh my god, that scooter didn’t exist then,” or, “That didn’t exist,” and that’s what I thought would happen. But when I started making the movie, I actually sorted all that out, so maybe it’s a line that needs to be resubtitled.

Here’s the thing, though, no matter what film you’re making, when you’re basing it on real people, there are gonna be things that are changed because it’s a two-hour movie and you’re telling a big story.

SINGH: I’d agree. The only thing that can truly be true then is just a CCTV shot for two hours.

Exactly.

SINGH: And also a 3D map. The world is in a globe, when you show it in a flat world, you get the land masses all wrong. You’re telling a lifetime story in two hours. I needed a license, and I said that, but somehow it doesn’t translate into English as well as I’d like it to.

No, maybe I worded it wrong. It’s poetic license. For example, I read that in real life, the mom offered the daughter a car to give up on the boy, and that’s not in the movie, but that supposedly happened. But again, you’re telling a movie, you can’t include all that stuff.

SINGH: Every piece of conversation, you’re right. In fact, one of the things that I so wish I could have included is how this thing came to light – you would have never known about it. The only reason it came to light isn’t in the film because this event is a lot more common than we like to believe. And at the same time, one of the reasons it came about is because the girl was Canadian. So basically, somebody from Canada becomes an international thing.

Second thing, the reason it came out is that the guys threw the body in a drain, like a one-foot drain. It’s a thing that they send water from fields to fields. The corrupt cop that they had on this side had jurisdiction on this side of that land, so when they dumped the body, they threw it and it rolled on the other side of that one-foot drain. So when people came in, they went, “Oh, it’s that guy’s jurisdiction,” and the wrong cop—or good for us—the right cop got called, and he went, “What the fuck’s going on?” The other guy was waiting for a call. He would come and say, “Somebody killed this person, blah, blah, blah.” They would have burned her and it would have been done. He would have never known of it. It’s that small event that I actually made this even come out and become a scam, something I would have loved to have included. But I just thought, “You know what? This is Romeo and Juliet, and it’s being told by an Iranian director.”

100%. I like talking about the editing room because that’s where it all comes together. What did you learn from early friends and family screenings that perhaps impacted the final film?

SINGH: Very little and a lot. Meaning, there was just something that I thought was so obvious that was working, and then everybody just said it wasn’t necessary and I took it out. To have the drama go back in front, there was a lot more intercutting…There was something structural that was there. It was something structural that, when I showed it to people, they just said you didn’t need it. So actually, I just took out seven minutes.

So when I showed it to friends and family, it was one feeling. Then when I showed it to the gang of directors that I kind of trust, from Mark to Bennett [Miller], who was phenomenal at notes, and Spike and Fincher, I did one screening for them, and I was listening a lot more to their women than to them. They were fantastic. But I thought Ceán [Chaffin] really cracked one of the big things for me. Fincher had pointed at a problem, but I couldn’t figure out a solution…then when I talked to Ceán, Fincher’s wife—not talked to her, she sent me a note—I realized in the note she had written what the problem was. It’s very rarely the problem that you think it is.

So, I think, usually on those particular things, I’m not very attentive, but in this particular one, it’s a low-budget film. I’ve got to make everything that I want. Usually, in the big budget ones, I stand behind them because if you’re making $100 million film, you gotta allow people to put milk in your coffee. Here I just go, “No, it’s a low-budget, it’s gonna be fucking black.” So, that’s how you get it. But at the same time, I’m just, “Are you understanding what I’m trying to say?” And at the same time, this is a bigger global film than just a Punjabi film, so I have to keep that in mind. So when hearing their notes, I just realized that you…have to hear their problem, you never have to take their solution. And It was eye-opening for me. And when I did that, it was the smallest note, it saved me seven minutes of film [laughs], so I just took out certain things that I thought were necessary and they were not.

You’ve made some really good movies, but I can’t imagine what it’s like when you’re pushing play on a screening room and you have Fincher, Spike, Bennett Miller, whoever else is in that room, watching your film for the first time. Do you get nervous when you’re showing it to such masters like that, fellow peers? What is it like for you?

SINGH: They’re not masters at all in that room! They are these phenomenally wonderful friends that only get together with me because my brother makes curry for them. They’re really wonderful and they’re so insightful and they are absolutely polar ends. You could not have a different person than Spike and Fincher. Mark, I would say, is quite in between, but they say very little, but what they say you really have to listen to. They were really fantastic. Now, I realize, I wish I had done this more because initially I’ve never done it with them, to ask for notes. Whenever Fincher’s asked me to come in and look at a rough cut or something, I just thought they just think, “Here’s the film,” and I would have a note like, “Oh, is that this thing? Oh, okay.” That was it until I showed this film and Bennett Miller talked to me and gave me notes, and I went like, “Jeez, that’s what my friends were asking, when I watch their films, to help them with?” I was just an idiot. [Laughs] It was so profoundly subtle and yet I would say it was a difference of night and day. It was just certain things that I thought was so obvious, and it wasn’t obvious at all, and this was before the sound was mixed and everything, so I still had enough to push around. So, do I get nervous in front of them? No, they’re just absolutely gods to me, and friendly gods, because they don’t believe in God.

I’ve spoken to David Fincher a number of times and that man is really, really smart.

SINGH: Yes, and funny, which is something that never comes across in any of his films. He is hilarious. I just wish that he would one day do a comedy. I don’t know how that would do, but he’s incredibly hilarious.

You’ve worked with your same DP a number of times now, Brendan [Galvin]; can you talk about the way you collaborate with Brendan before you step on set, and then on set, are you guys figuring out if you’re gonna do dolly shots or if you’re gonna do certain things before you step on set? How much is it in the moment that you’re realizing, “I want to do it like this?”

SINGH: It’s shot before we get there. For me, it was 24 hours before I decided to shoot this movie myself. I had two people that I was thinking maybe they’ll do it because Brendan was supposed– See, I’ve known Brendan now for close to 25 years, so I’ve always had this hierarchy of people – my college professor was my DP who did The Cell and everything with me, Brendan used to be a focus puller, and Colin [Watkinson] used to be the loader, so there was a chain out there.

So after many years, when I was going to do The Fall, Brendan had just come back and he turned down doing The Fall because he had some family commitments, and I turned to the loader, and I just said, “Would you like to DP this movie?” And he said, “Uh, I haven’t done that before,” and I said, “Okay, let’s do an ad next weekend.” We did an ad, and I said, “There, are you confident?” He said yes, and we went and did The Fall. So it was fine, and I worked with Colin all that particular time. This time when he came out, Colin wasn’t available for some reason and somebody else that I had worked with wasn’t, and I just thought, “You know what? The time is running out, I’ll DP this myself.” And I just thought, “I would love for Brendan to do it, I hope he’s available,” because he had initially thought maybe he wasn’t. Suddenly, when he became available, I just went, “Great,” and we have such a shorthand, is the reason, I would say.

I told him that, “We will have two cameras in 95% of this for performances because the guy is kind of like a little child who hasn’t acted before, so we might not get repeat takes. We will do that, but there’s practically no move. Maybe once or twice, we will need one shot. I think I have a dolly.” I told him we’ll need a dolly because I couldn’t architecturally do it with the bank, so that was it. So I told him, “Lose all the other equipment, there is no crane, there is no nothing, there’s no drone, there’s nothing. It’s going to be shot like this.” And it’s not usually what I’m known for.

So when we went out there with the actors, I went to the village where we were shooting, which was rough because I spoke Punjabi, they spoke the correct language…she didn’t speak Punjabi that well…but she didn’t speak English at all. So I took them to the places and I would sit with them, and I’d just say, “This is what the scene is about. Let’s just talk it through.” So after they would talk it through, I’d draw usually what I call crow’s feet – I have a plan and I draw a camera angles. Just this. And then with the DP, I just talk through that, and I just say, “This and this, this and this.” So the text scout’s done very quickly because my part is done because I’ve kind of shot it before we get there.

Brendan is phenomenal, very quick. Like, literally doesn’t exist. So when you go out there, it’s just phenomenal, no ego, no nothing. And working with Indians out there, it’s fucking harsh just because it works much, much, much, much, much easier now than it used to be, like, 20 years ago. Plus when I went, it was a nightmare, at least for me. Because I used to have a white crew and the people who had to park trucks or the catering or the food or anything would just come to me with the problem, saying, “Where shall I park my truck? Who needs to be fed?” And I go like, “Hey, I’m the director, ask that guy.” “But he’s white,” and I go like, “Fuck, he works for me! Just go…” That was difficult. But now, all that seems to be sorted. So Brendan came into his own. He went out there, all the guys were brown, and he told them, “Listen up, this is how things are gonna go much more smoothly.”

Then in the end, it just flowed as quick as it did because we shot it very fast. And the cut was finished within 48 hours of the last day of shoot. I was cutting every night because I was editing it. So every day we’d shoot it, it became much more, if I could ever call it a Coen Brothers’ approach, it was much more that. I would do that, assemble it at night, and then the assembly and the cut are practically the same except I took out seven minutes.

Yeah, I know a lot of filmmakers, Guillermo del Toro and a few others, that they edit every night. I mean, it’s a lot of work but it also helps if you realize, “Oh, I need to get that other shot,” you know it when you’re cutting.

SINGH: I’ve almost never done that. I just have never gone back for a reshoot, and then guess what? We did have to do it on this one because the people who were cast as the—if you have to call them a villain—the mother and her brother, they couldn’t get the visa for Canada. I shot in India and I arrived out here, and I was basically, again, maneuvering and working with what the capacity of each person was, and suddenly while coming to Canada, those people were denied the visa. And I had to shoot within two weeks or whatever it was. Then they showed me the actors and it was a gold mine. It was the exact moment that I would have wanted in the very beginning. So when I got her, we went and shot that. Then I realized that the India part there was very little of her, but that needed to be reshot even though most people can’t tell one guy wearing a turban from another guy. I just thought somebody might notice [laughs], so we went back and put them in. So the only reason we had to do that, to pick up stuff, was because they couldn’t get their visa.

I could be wrong, but you shot for 50 days in India?

SINGH: Actually, it’s much less. I just realized. We shot five days per week. I just said it just has to be because I’ll crash. I’ll need to edit and have everything set as we go. So it’s five days per week is what we were shooting…It wouldn’t have been more than 40, much less than that. Let me get back to you on that. I said 50 to somebody the other day, and I was just like, “Hey, that wasn’t true at all.” We didn’t have that many days to shoot. We did the rehearsals when they came in, then we just shot. Nothing went wrong except the stunt thing got scary and then I just stopped it and embraced what was happening.

Yeah, it’s pretty crazy. It’s not a lot of shooting schedule.

SINGH: No, but it was magical. Everybody felt like we were doing something special, so it just worked very, very well.

It’s pretty outrageous that the people responsible for this did not go to jail and get extradited immediately. Hopefully this film is going to help raise awareness on the whole issue, but what’s your take on everything?

SINGH: Well, I would say in this particular one, it was quite strange. For one thing, they didn’t get his thing because Canada would not extradite them. The Indian system, or let’s say the courts or the cops and all, everybody knows in third world it’s quite corrupt. So when you go out there, they had this thing and they’re trying to extradite the guys from Canada. Canada rightly is saying, “We don’t believe that this was a fair way to put forward everything,” and they just wouldn’t extradite them. It took 22 years, and the moment we started shooting, or maybe it was the week before, they extradited. So, they ended up in India as we were starting to shoot, but they’ve appealed the case, so God knows how long that could take. They’re out, or if I understand correctly, might be out on bail or whichever way it goes. It’s a process. The two countries on conversation just did not agree with it.

And also there’s a lot of stuff– I just don’t agree with the mother’s side and all that particular side at all. But for me, I was refusing to look at her as– and most of how Indians and, I would say, the Western audience will look at it and just go, “Yes. That person is bad. This is bad.” That’s it. And I would just say you see a lot more subtlety in this one for the Indians because if anybody has been through a joint family system, they’ll understand that I actually put the other side’s side forward, also. To a certain extent, the words will probably not mean anything to a Western audience, but when you see something like that, there’s a couple of no-no’s that you have that these people did. Like, when you have the main reason a mom would do something like that– Because, again, to make her that character, I was refusing to have her play just a villain. I was just thinking, [if] I could think of the only pure person I know, I think of my mom, and I just said, “If my mom was in here, how do I make her do something like this?” And it was easy.

It’s more of a cultural than a religious problem. It’s just that when immigrants move from one country to another—you see that with the Irish, you see it with everybody—the moment you move, you might want to get the F away from the country, but when you go away, you’re among such aliens that you grab at cultural straws. Then you become a lot more patriotic/correct to the older culture than you were when you were back home; you forget why the fuck you wanted to get out of there. You go here and you hold on to that; meanwhile, back home has evolved, people have become a lot more liberal and now they have mobile phones, the girls go out, all that. So when they come to Canada, they’ll go, “These guys are pretty backward,” and that almost happens in every culture. I would say, like, if you see the Bostonites living in the ‘70s, and the Irish in Boston, they were the people who were supporting, let’s say the IRA or anything like that. Whereas, when you go back there, it wasn’t that at all if you had to look at the numbers. It’s just that now, it’s the same thing with the Punjabis; when they come out here, they grab at those straws.

One of the things that happens when you have a joint family is that if the house is tainted by a particular brush—that their daughter ran away with this thing, or she married a person, or she was a prostitute or whatever, and they consider all that—all the other girls will suffer from it. So, you might have 10 girls living in that household that will now have to marry a lot more below where they were supposed to get married or not get married at all because one person did this. So with the person in that household, like a mother or somebody, you have to then make the choice on, “I’ve lost this kid, now do I cut my losses and go against her so the other nine can get married or do I accept this?” And she made, I will say, the wrong choice. She went against that particular one trying to protect those women. And I’ve had a couple of women, even when we were shooting this, the actress said that, “I can understand.” I said, “I don’t understand her.” I understand her, I do not sympathize with her. So that’s what I was trying to kind of put in there, was if my mom was in a situation like that, “None of my other children will get married because of this girl doing this, do I cut my losses?” And that’s, I think, kind of what happened.

That’s a great answer. I am curious, though, what it was like for you when you told your dad or your family that you wanted to be a filmmaker instead of going into something more structured or something more solid?

SINGH: No, it stopped everything. My dad was an engineer in Iran since we were kids, so we traveled a lot as a child. And the moment he found out I wanted to study film, he just said, “You’re never going abroad.” So I never went abroad because he just said. If you’re an Indian or Jewish or Armenian, you’re a lawyer or doctor in India…there isn’t really another category. So their whole thing was like, “Just get into this.” So I lied and cheated like mad getting through college in India, in commerce, to come over and then tell them I wanted to study in film. And of course, got just cut out of the family and written off, and it worked for me.

Did he eventually forgive you?

SINGH: You know what? I found that out much later because after that, he retired to Vancouver and was running a laundromat. And then I was told that he would say proud things about me, but did I ever hear it from him? [Laughs] No. Well, it was hard for him to kind of come to terms with that whole world that he grew up with where everything has got to do with how hard you work and how much you earn and blah, blah, blah. I remember one time a job got canceled after 10 hours of booking, it was a 10 day shoot, and it got canceled. I literally sat down and I thought, “In those 10 days, by not doing that job, I made more money than my dad, who was an engineer, made in 35 years working in Iran.”

Any parent will want to play a probability game with their children and try them to get into a field and actually get them work. I just burned every bridge behind me and I just succeeded with it. But their thing is just to say, “No, there’s very little chance that you will succeed.” So, he was very proud, but he was just trying to make sense with the world with the only definition that he knew, which is education is everything. As he would say, “The Mullahs or the communists or anybody will come and they take everything away from you, but nobody can take your education away.” So educate, educate. That was it. They’ll always say, “You can study whatever you want, but you know so-and-so’s son? He’s a doctor. You can do whatever you want!”

So all those cultural pressures are on you. I tried really hard and I realized I just wasn’t smart enough and I couldn’t make it. I was competing with people who, without opening a book, could kick my ass in any physics problem. And I just said, “When you’ve got…a billion people to compete with, that’s a lot of competition.” Find something that you love or you might be good at, you might have a better chance. A parent will disagree.

Yeah, I’m very familiar with what you just talked about because I decided to move to LA and start a website and then, you know, it worked out for me. I got lucky.

SINGH: Well, one thing is luck and mainly you play the probability game. Probably for me, they just lucked out because I had grown up in Iran watching television in a language that I didn’t understand, and then it took me years to figure out that’s why my storytelling is so visual. I would always look at that. I remember when we would go back to school on Saturdays, we had a storytelling class, and I’m always at the head of the line because I was the guy who had gone abroad and seen TV. I would tell them what I thought were the movies that I’d seen. And until today my friends turned around and go, “You’re an idiot! That wasn’t…” Because I remember I saw Get Smart and I would tell this story as like a really James Bond cool guy because they had removed the laugh track from Get Smart and it was dubbed in Persian. And basically, “There was a guy who could call anybody through his shoe and blah, blah, blah,” and I didn’t see that as over the top at all! I just thought, “He’s fucking cool,” so I would tell that as a story. Then years later, they just went, “That’s supposed to be a comedy,” and I was like, “I didn’t know that!”

So for me, I grew up with that whole thing of basically visual storytelling. I end up in a world in LA just learning I couldn’t get into any college. Then basically I had to lie and cheat my way into city college under a different name, and when I got there that got me a scholarship into Art Center. Art Center is just known for visual films. Most of the schools [for] storytelling, like UCLA and UC, I couldn’t get into any of it, including Art Center. Later on, when I got into it, in my batch are people who I think are probably everybody who all the critics would claim are quite, you know, the worst guys to make movies. They’re like me, Zack [Snyder], Michael Bay, everybody. We literally came in together, and we were just taught how to polish a turd, is how I would put it. [Laughs] It’s how to make things look good, and that was all I cared about. I said, “I know the stories I want to tell, I want to know the front end of a camera from the back end.” And that’s all I went to that school for.

You come out of there and then suddenly the world, the way to break in let’s say…is all the writing for all the directors. The moment we were graduating, the thing that was the natural stepping stone turns out to be a visual medium. It was music videos. So we got a natural jump into that, and then straight away, I realized I didn’t want to make movies at least for another decade or something, so where do I do advertising? And I realized I liked it much more in Europe…and just at that time, lo and behold, in Europe satellite is becoming big. And what they’re doing, people like Levi, Nike, anybody, are just looking for visual storytellers. They’re all local ads, but they make one ad that runs in Germany, Italy, France, UK, everywhere, but it has to be told visually, just with one tagline that you can write in a different language if you want. I was just at the right place. I was the hairy guy and the temperature fell, or I was the guy with no hair and the temperature went up. I was just just in the right place.

So, luck has a lot to do with it. But I would just say the probability game is what I was playing and I was very aware of it, that my forte was that, and then I went over there, and not in America. It took me another 15 years before I came back to America to make commercials because here it is so dialogue-based, it was so everything else-based and I just wasn’t interested in it. So I was a little bit aware of it, but you’re right, it is luck. But a lot of it has to do with when the door opens, how to put your foot in.

I read that you’re doing Nanda Devi, do you think that’s your next thing? Do you think you’re gonna be making another movie?

SINGH: Not really. I’ve never looked at IMDB or Google, or anything like that. People always ask me things, and then I wish I could go and correct them. It was just something that had been told to me earlier and I just thought that would be an interesting project, but it hasn’t really moved. I think there’s another whole bunch of other projects that I think will go a lot before that. But that is an interesting project to me, I still do like it.

Well, my question is, it’s been eight years since your last movie, do you think it’s going to be another eight years or do you think you’re going to be making another film or a TV show in the next few years?

SINGH: I think it will happen in the next few years, but if it takes a decade or two, I’m in no hurry. I live very much in the present and loving what I’m doing. I love cycling to my son—I finally got a car here—but I cycle to my son, which is 55 minutes away, and he comes and spends the weekend with me. I’m just having a lovely time going anywhere I want in the globe and making these little ads that everybody hates except me. I just love the process.

There’s a few films that I do like right now. With Dear Jassi, because I think I booked the goalpost on what I’m going to do, so suddenly the offers have shifted to a different side, which is wonderful. So I do agree with you, I think I will. And at the same time, I want to do a movie in India, a big movie in India, and certain stuff has just come that way. I turned those guys down, saying let me get this devil off my back first, and they didn’t blink. They came forward. And so with them, I’m gonna put together, hopefully, an Indian tale.

I was gonna say not everyone hates your commercials.

SINGH: [Laughs] Thank you. But I would say they hate it because they want me to make movies. They’ll just say like, “Why are you wasting your time?” I said, “It’s not wasting, I’m just learning my craft. I’m just trying to figure out what to do.”

RRR exploded into America and another Indian film, Kalki 2898 AD, that’s another big sci-fi, the first big budget sci-fi movie made in India with an all-star cast. I spoke to them at Comic-Con. Do you feel like India is all of a sudden sort of getting its due around the world in a way that it hasn’t?

SINGH: I’d say it’s getting its due in America. It’s always been, if you go to Africa, if you’ve ever been to China and in any of those places, India has always been massive. Their cinema has always been massive. It just didn’t cross over to this except through arthouse. But now, because of Netflix and streaming and everything, every now and then when you go and you end up watching one of those, you realize that the license of engaging the audience is so different from the West that if you buy that pill, it’s an incredible trip to have. And I’m always trying to find out what the pill is when I make my films. The films that you make in the East, they require a completely different pill from them in the West.

Like, let’s say the example would be like you have your Supermans and all that. The reason the sequels do a lot better, always, than the first one is the first one is what you call an origin story. It’ll be about this guy who can fly because he comes from another planet, he’s weak from there, he misses home, blah, blah, blah, blah, okay! And about an hour and something has passed, now you tell a little story. The second one, there’s this flying guy and you can do whatever you want, and it’s a great adventure…So it’s three hours of third act. [Laughs] That’s why they are as entertaining as they are.

But to the West, when you research your film here, they call it bad laughs. They just say, “Oh, that’s too kitsch.” It’s just that that industry is used to that engagement pill, and I think it’s what saved them. I think it’s what killed Italian cinema and French cinema or any of the European cinema. I’m talking about the commercial one, phenomenal arthouse stuff going on there. The reason the commercial one died is because the rules of engagement with the audience were the same as Hollywood, Hollywood just outspent them and that culture is used to watching the movies now, but they were back then dubbed. Once you went out there, nobody cares that he made a low-budget film, why did it look so cheap compared to Mission: Impossible or blah, blah, blah? So you were competing with those boys and their industry died.

The reason China’s and India’s, I think, is surviving it for the same reason. You can have a really serious moment and then your dog can have a flashback in the middle of a serious moment, and it’s not funny. It’s part of the structure, and you go with that and the audience take it. So I would say that in the West, you made that separation in opera and cinema. You’ve done that where, as they say, the fat lady sings. When she sings and the guy says, “You are beautiful,” you go, “Yeah, that’s okay.” You do that in cinema and you go, “Really? Look at her.” You go that way. Whereas in India, a guy who’s in his 30s will play himself in his high school, and you go, “Yeah, he’s the actor.” So, they buy that pill. So that rule of engagement is different, and I think that’s what saved them.

All the flying and fighting and the Kung fu fighting, the Chinese stuff, their rules of engagement were different. So those two cinemas, I personally feel—I’ve never seen this written anywhere—I just think it’s why they are the only two competitive cinemas compared to Hollywood that have survived in big cinema. As far as arthouse is concerned, anybody who has a phone now can make any phenomenal film they want. The problem is how do you get eyeballs on it? So now it’s about distribution, so it’s something else. But I think the Indian films, just streaming and all that, every now and then people stumbled onto them and they went like, “Hey, this is just a different form of entertainment.” If they start biting into that film more and more, then—I don’t know if it’s a good thing—the fusion will come.

Yeah, I went to a screening at the Chinese theater in Hollywood for RRR after it had been out for a while and it was the craziest experience with people dancing in the aisle. I really do think that opened the door to a lot of people to look for more cinema from India as something that they want to see.

SINGH: It will be good for the West to do that. But in India, when you go, it’s almost like a radio. When you go to see the thing, you can do other things while watching the film for the fifth time in the cinema. People do that outside. But all the films, at least when I grew up, you never saw the movie once. You saw it five to 10 times, you knew the songs, you danced. If it was a religious film people threw coins at the screen, all that shit just goes on. [Laughs]

Dear Jassi world premiered at TIFF and doesn’t yet have a release date.