Film fans recently received the sad news that the legendary British genre filmmaker Mike Hodges had passed away at the age of 90. Hodges’ name isn’t brought up as often as it should, which is partially because of how versatile his filmography was. Between the tongue-in-cheek science fiction opera Flash Gordon, the low-level gambling thriller Croupier, the dark mystery comedy Pulp, the horror sequel Damien: Omen II, and the psychological thriller Black Rainbow, Hodges took chances on different genres, and generally found success in them all. However, his crowning achievement was actually his debut film; 1971’s Get Carter isn’t just one of the best crime thrillers ever made, but a film that essentially created the neo-noir revenge style that so many modern filmmakers have adopted.

What Is ‘Get Carter’ About?

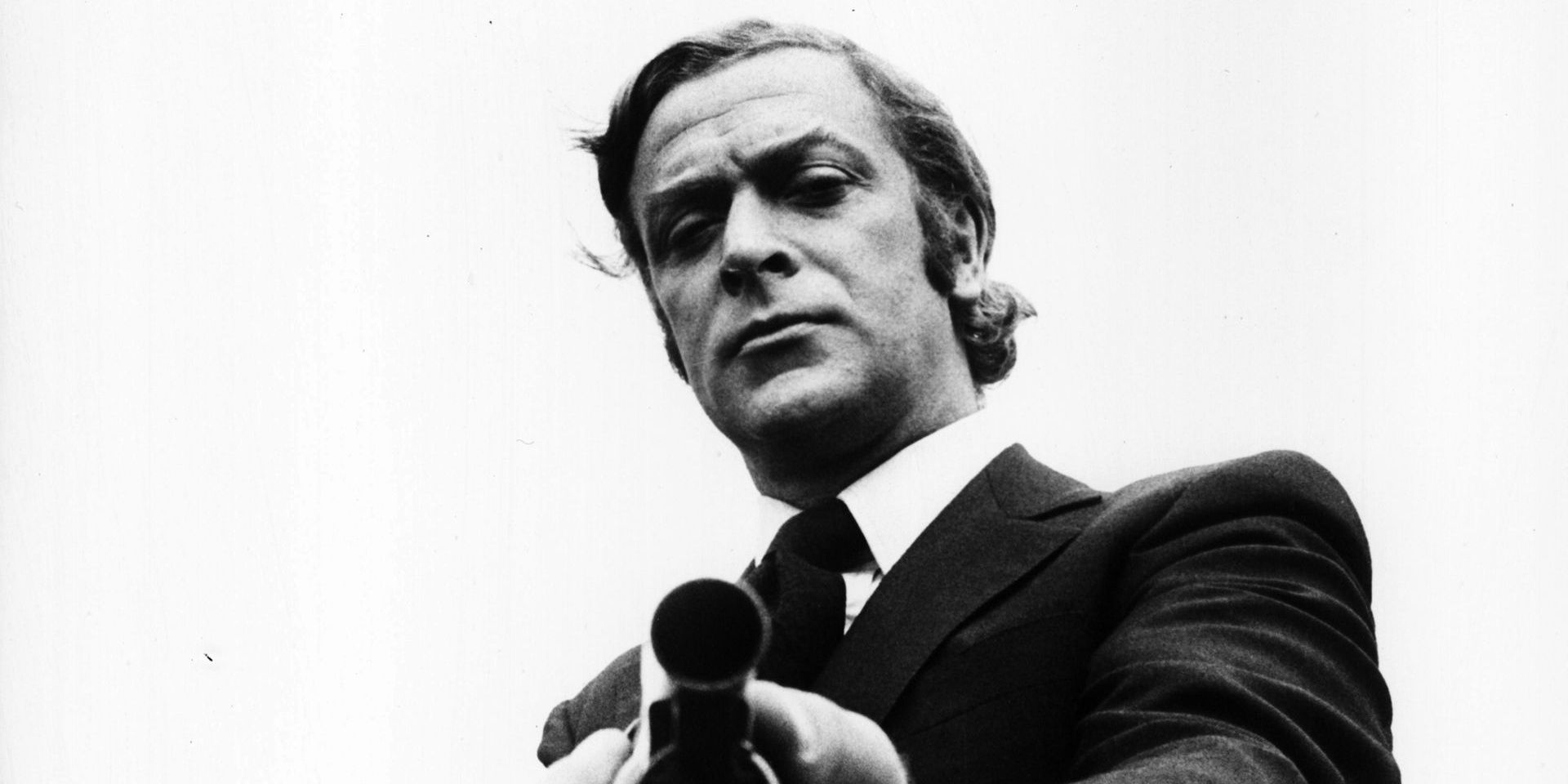

Get Carter follows the London gangster Jack Carter (Michael Caine), who returns to his hometown in North East England to investigate his brother’s death. Given his experiences with lawful malpractice, Carter suspects that there’s more to the “official story” than what the authorities have revealed. What follows is a painstaking investigation into the circumstances of his brother’s death that’s interrupted by brief, yet shocking moments of violence. Rather than emulating the crowd-pleasing nature of the James Bond films, Hodges worked with acclaimed cinematographer Wolfgang Suschitzky to give Get Carter a quasi-documentarian feel.

Action cinema was in a transitional period in the 1970s; while action cinema didn’t truly evolve until the 1980s, we saw some attempts at darker spy and espionage thrillers like Dirty Harry that attempted to imbue a political message within their material. Hodges wasn’t trying to elevate the themes of Get Carter beyond their pulpy origins, but he improved the craftsmanship on every level. By placing great actors, taught sequences of suspense, and unusual soundtrack moments, he created an idiosyncratic, hallucinatory pulp thriller that clearly had an impact on the next generation of neo-noir filmmakers. It would be hard to imagine the careers of directors like Nicholas Winding Refn, Guy Ritchie, Matthew Vaughn, Michael Mann, George Miller, Abel Ferrara, or Chad Stahelski without the template that Hodges had set.

‘Get Carter’ Broke the Mold

The only prior action movie that Get Carter could be compared to is John Boorman’s Point Blank, a similarly idiosyncratic mystery thriller with a strong emphasis on subversive music and stylistic escapades. However, Point Blank is a much more philosophical work; Lee Marvin’s character is wrestling with the nature of his mortality as he questions his sanity, and the audience is forced to emulate a ruthless criminal who may have been taken advantage of. Hodges wasn’t attempting anything that grand and ambitious with Get Carter, because on a story level it’s nothing more than a basic revenge thriller. The label of “elevated pulp” seems derogatory, but it’s the best way to describe something like Get Carter that takes the narrative beats of a dime-store detective novel and reworks them into a relentless thriller.

Hodges was noted for his collaborations with Caine, who had quickly risen among his contemporaries to be one of the best actors of his generation. While Caine’s work in Zulu and Alfie had certainly proven that he was a compelling historical or romantic lead, it was odd for him to stop sanding off his edges and do something so grimy. The genius of casting Caine was that he didn’t have the inherent “hard edge” of something like Steve McQueen; he still acts and proceeds like a gentleman, giving an edge of dark comedy to any of the moments where he formally introduces himself to someone before brutally attacking them. Casting is the most important step in creating a neo-noir story; Thief would collapse without the steely charisma of James Caan, and John Wick would be a confusion of tone without the semi-ironic delivery of Keanu Reeves.

‘Get Carter’ Aligns With the Rise of the Anti-Hero

The beginning of the 1970s were a time in which audiences were slowly adjusting to the idea of what an “anti-hero” really was; even if the deeper themes of something like The Searchers had been lost on casual viewers, by the time that Taxi Driver was released even non-film buffs could recognize that Travis Bickle isn’t intended to be a hero. Michael Caine was an important part in that shift of what a movie star could be; even if the men who killed his brother are ruthless, selfish gangsters, Jack isn’t above torturing and humiliating anyone he needs to in order to find the next clue. Even if you’re not following every piece of the narrative puzzle, it’s easy to invest in Jack’s trajectory as he shows flashes of animalistic rage within his investigation.

Hodges had waited to make his debut until the tail end of the 1960s, where relaxations in film censorship allowed him to include more explicit content. With the freedom to be more realistic in his depiction of London’s crime scene, in an interview Hodges said that he wanted to “use the crime story as an autopsy on society’s ills.” While this is mostly a relentless action film, the backgrounds are peppered with details of the social disenfranchisement, police corruption, economic inequity, and xenophobia that have overtaken the impoverished area of London. While Hodges doesn’t feature many moments where Jack stops the narrative to “explain” why these things are problematic, the audience is forced to take a hard look at the realistic, systemic issues that have put Jack in this situation where he’s forced to take the law into his own hands; it makes the entire experience even more eerie.

In ‘Get Carter,’ No One Gets Out Clean

According to Steve Chibnall’s British Film Guide on Get Carter’s production, Mike Hodges resisted inserting a voiceover from Jack that would have given him a more empathetic backstory involving his brother. This was another brilliant move, as the audience has to be somewhat removed from Carter to enjoy his mission. He’s far too brutal to be “relatable,” so adding a sense of mystery to his motivations and feelings makes the action scenes more dynamic. As for the action itself, Hodges resists any over-choreographed battles in favor of chaotic brawls. Carter’s final beatdown and torture of Eric Paice (Ian Hendry) has the quasi-documenatrain realism that Paul Greengrass would later adopt for the Bourne films.

Hodges pushed the audience to their limits; if Jack doesn’t really get any resolution from his bloody rampage, then are we at fault for enjoying it? What does it say about our fascination in violence if we were invested in watching Jack go between jazzy nightclubs to find his next unsuspecting pawn? It was a fascinating example of arthouse cinema disguised as a mainstream thriller, which signified that Hodges’ work would have lasting ramifications on cinema long after he was gone.

![AI Experts Don’t Believe AI Tools Will Lead to Mass Job Losses [Infographic] AI Experts Don’t Believe AI Tools Will Lead to Mass Job Losses [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/gcXE1_Da13Oz-JAszjUwb6v5UqMp2MFMjDAIXPbLad0/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9haV9qb2JfbG9zc2VzLnBuZw==.webp)

![How to Align Your SEO Process With AI Discovery [Infographic] How to Align Your SEO Process With AI Discovery [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/9P2R5ZZoepHyBzf0CW-n2EgWRhr-_OdwsznROe_GvnM/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9haV9zZWFyY2hfaW5mbzIucG5n.webp)