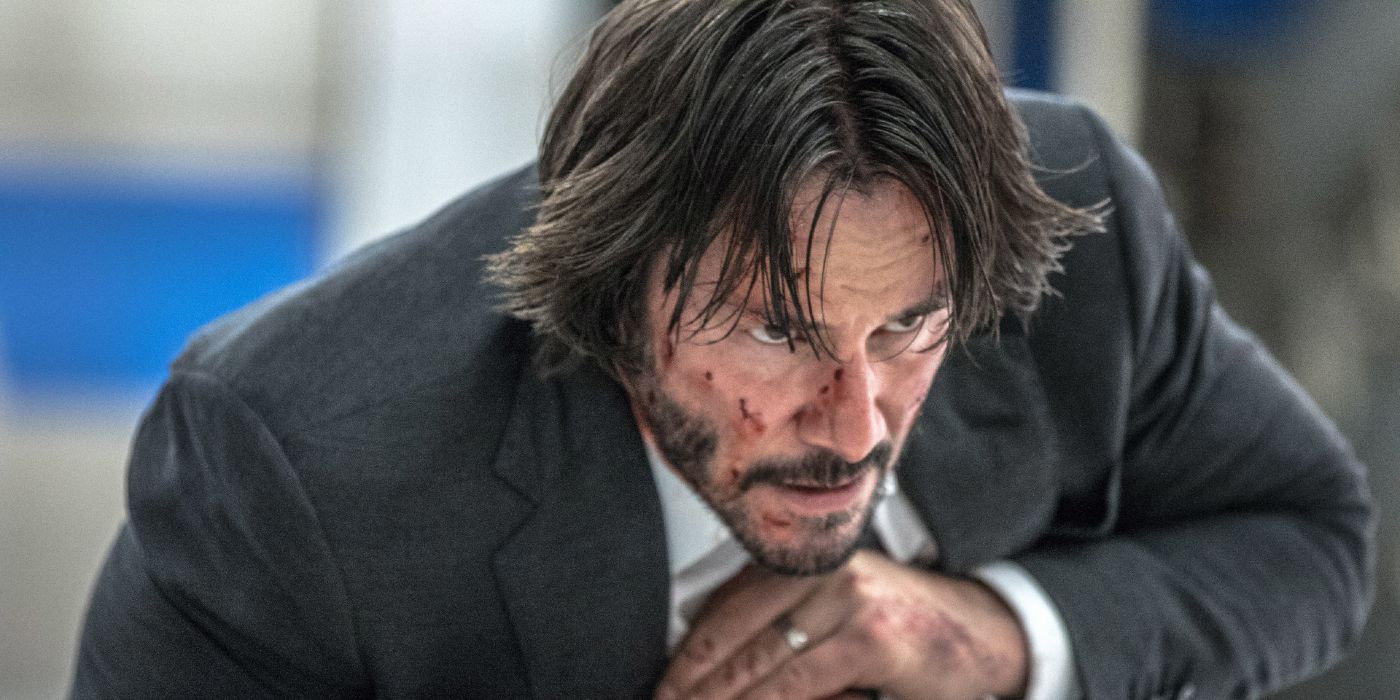

Why does John Wick‘s gently absurd premise work so well? Why is watching Keanu Reeves mow down bad guys in the name of avenging his murdered dog entertaining enough to spawn a multimedia franchise? Reeves at his finest is undoubtedly a draw, and there’s been plenty of sympathy for that poor puppy (obviously, I wouldn’t copy his actions if someone hurt my beloved cat, but still — I understand you, Mr. Wick). And therein lies the draw: John Wick embraces a quiet, sly silliness that borders on parody. It’s a movie that knows what it is: bloody, visceral, and self-aware enough to wink at the audience from time to time with an expertly placed one-liner. Director Chad Stahelski (a former stuntman) and writer Derek Kolstad struck the perfect balance of pushing circumstances to the edge of ludicrous while still demonstrating absolute reverence for the Hong Kong action cinema that inspired Wick.

Although John Wick: Chapter 2 and John Wick: Chapter 3 — Parabellum crank up the absurd factor, the first film didn’t lack for wry humor. The world of John Wick 2014 was smaller, and its goal was distilled: a recently widowed assassin takes out his grief by wiping out the Russian mobster (Alfie Allen‘s Iosef Tarasov) that broke into his home, stole his car, and killed the puppy that his late wife adopted to keep her mourning husband company. As such, the film’s tone is suitably dourer, and the hints of the intricate assassin world Wick once inhabited are just that: hints. The swanky Continental hotel where assassins hang out is fascinating; the Blade Runner-esque color palette suggests a dangerous urban landscape; and there’s all this mythology that follows Wick like a second shadow. These touches enhance the world and add enough texture for it to feel tactile without awkward info-dumping.

What Makes John Wick Movies Great?

Wick’s prowess as a dealer of death is actually the best example of the franchise’s tonal balance. He’s legendary throughout the assassin community, an unstoppable Terminator-style figure that inspires awe as much as terrified resignation. The audience sees none of Wick’s murderous history, however; it’s all conveyed through dialogue that reads like a modern fairy tale or a superhero origin story. Viggo Tarasov (Michael Nyqvist), Iosef’s father, flat-out abandons Iosef to his fate because that boy’s in deep sh*t. But he still seethes over Wick’s mythos, especially how Wick once killed three men with a pencil. “Who the f*ck does that?” he demands.

The pencil line, especially because it’s intercut with Wick smashing open a concrete floor to unearth a cache of guns and ammunition, is darkly hysterical and makes the film’s intentions clear. The nightmarish aura surrounding Wick is a perfect mix of humorous, unsettling, and more than a touch of cheering him on because this is fiction, and we can do that.

Another example of Wick’s tendency toward satire follows the film’s first true fight sequence. All the gunshots prompt one of Wick’s neighbors to call in a noise complaint (oops!), but the policeman at Wick’s door is a complete subversion of expectations. He and Wick are friendly and when he spies the dead bodies in Wick’s hallway, he lightly asks, “You, uh, working again?” It’s an oddly playful contrast to Wick’s massacre, which was played straight, and could have walked straight out of a Saturday Night Live skit.

Then there are the shots that are just fun: Wick finally achieving his revenge happens in slow-motion, his black suit jacket floating stylishly behind him as he approaches a cornered Iosef. Stahelski and cinematographer Jonathan Sela often have Wick emerge from the shadows into film noir lighting that illuminates only half of his face — obviously representing Wick’s spiritual duality. The words “epic” and “badass” aren’t inappropriate here.

John Wick’s Gun-fu Is So Good Because It Respects the Art Form

Truly, that’s because John Wick’s fight choreography is the definition of epic. Much has been made about how Wick resurrected Hollywood gun-fu, but the reason Wick’s action scenes are captivating is simple: Stahelski and his crew understand that gun-fu is an art form. Renowned Hong Kong director John Woo originated gun-fu in the 1980s and 1990s, and Hollywood began imitating the style in the early 2000s. Rather than aiming for style over substance, Stahelski treats the martial art with the respect it deserves. The meticulously complex choreography is remarkable on its own but also graceful in execution, in no small part due to Reeves’s mastery over physical performance. Not enough praise can be heaped upon his commitment to stunt work authenticity; as such, the violence in Wick just hits differently. Wick is visceral and efficient, savage and ruthless, his actions both second nature and demanding all his body can give. He bleeds, sweats, and just keeps going with those bangs falling into his eyes.

Unlike other action franchises where the sequences grow stale and repetitive, the wildly unfortunate scenarios Wick finds himself in remain creative, especially in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3. I mean, where else would you see a man killed with a library book (Wick is the only fictional character allowed to commit such a transgression), or a rain-soaked Reeves riding a horse through the streets of New York while pursued by armed men on motorcycles? Wick even fights a chatty fanboy who keeps trying to impress him after Wick has impaled him on his sword. The production team’s commitment to the combat quality never wavers, but tossing in absurd kills (Wick demonstrates his pencil technique) or moments like Wick tossing his empty gun into an opponent’s face interrupts the action enough for us to cackle. Since Wick’s skills are well-established, there’s room to play.

The Worldbuilding in John Wick Movies Is So Silly, It’s Fantastic (& Fantastical)

Indeed, the second and third films are when the franchise openly indulges its more outlandish side. The tone lifts to something lighter as if the director’s winking at the audience, and the intricacies of Wick’s assassin world slowly unravel. There’s far more under the surface than the audience could have guessed: an organization called the High Table oversees the assassins’ actions like an executive board runs a corporate business. Santino D’Antonio (Riccardo Scamarcio), a member of the Italian mafia, forces Wick to kill Santino’s sister by invoking an unbreakable blood oath that the two share. When Wick breaks the rules and kills Santino on neutral Continental property, the High Table expels him from their ranks and puts a bounty on his head. A snazzily-dressed High Table Adjudicator (Asia Kate Dillon) even arrives to clean up the mess that Wick made. The heavily tattooed High Table secretaries use rotary phones and old computers, and apparently, every person on the streets of New York is an assassin interested in Wick’s bounty. Oh, and John Wick isn’t his real name; he possesses a mysterious backstory that involves a Russian crime syndicate.

Looking at it all together, Wick almost counts as an urban fantasy. The worldbuilding is a smorgasbord of near-lunacy yet too stylishly done to critique. We don’t need to know why the guy who oversees the High Temple lives in the desert; he just does. Of course, John embarks on a quest to find this man by scaling endless sand dunes under the blazing sun and starlit night skies. And when Reeves is reunited with his Matrix partner Laurence Fishburne, that’s about as self-aware as you can get. Fishburne chews the scenery with relish, demanding of a betrayed Wick, “Are you pissed, John?” To which Wick, a perpetually exhausted murder machine with a broken heart of gold, delivers the classic Keanu Reeves reply: “Yeah.” He’s deadpan yet fierce, summarizing the franchise’s tonal balance in one word.

So What’s Next for the John Wick Franchise?

With John Wick: Chapter 4 on the near horizon, several factors are assured. We’ll learn more about Wick’s madcap world and the people who inhabit it; viciously creative carnage is a given. The legendary Donnie Yen will face Reeves in a cinematic showdown for the ages. As for the rest, fans can only guess, because Wick isn’t beholden to the action film rules even as the creators revere gun-fu’s artistic history. Somehow, this beautifully unique balance of cartoonish satire, radically inventive bloodshed, and examining the psychology of an achingly sad man unsure of what to live for, weave into a cohesive whole that’s one of modern cinema’s most satisfying action franchises.

![Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic] Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/9e7sW3TubFHM00yvXe5zvvbhAVriJiGqS8xmVFLPC6s/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zb2NpYWxfc3ByaW5nX2NsZWFuaW5nMi5wbmc=.webp)

![5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic] 5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/Hv-m77iIkXSAtB3IEwA3XAuouMwkZApIeDGDnLy5Yhs/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9saW5rZWRpbl9zdHJhdGVneV9pbmZvMi5wbmc=.webp)