[ad_1]

Japanese director Kōji Shiraishi may not have worldwide popularity, but he is a very skilled horror director. He is probably best known to international audiences for his spin-off crossover of the Ringu and Ju-on franchises, Sadako vs. Kayako, which was released on Shudder in 2017. He was also at the center of controversy in 2009 when his exploitation torture porn horror Grotesque was banned in the UK. His 2004 feature debut, Ju-Rei: The Uncanny, made little impact, but he followed it up with the well-received found-footage horror Noroi: The Curse a year later. Understandably regarded as one of the best of its kind, Noroi: The Curse subverted audience’s expectations and challenged found-footage conventions. Shiraishi found his flair with the subgenre and went on to write and direct several found-footage movies in his career, as well as starring as himself in some of them. He continued to bring audiences unique additions to the subgenre, and he is not done with it either with the upcoming movie Welcome to the Occult Forest in which he is once again playing a fictionalized version of himself.

Noroi: The Curse is not only Shiraishi’s best work, but it is also one of the most overlooked horror movies in recent memory. It completely ditches the conventions audiences have come to expect with found-footage horror, and delivers strongly on scares, characters, and plot. More recent acclaimed found-footage horrors such as The Medium and Incantation certainly appear to have been inspired by the professional aesthetic of Noroi: The Curse. Despite a limited release outside of Japan and still no DVD/Blu-Ray release, Noroi: The Curse has a passionate following of horror fans who continue to champion it all these years later. It was released in 2005, two years before found-footage was re-popularized with the first Paranormal Activity movie, but Noroi: The Curse is very different stylistically. It has something of an epic feel to it, running at almost two hours long, and comprises countless bits of footage from reality TV-shows and news stories. The plot sees paranormal researcher Masafami Kobayashi (Jin Muraki) investigating a series of strange events occurring all over Japan. The investigation takes him down a never-ending rabbit hole in which he comes across a horrifying curse and encounters a lot of bizarre characters.

A common complaint with found-footage movies is the nausea-inducing shaky-cam effect, which can have fairly mixed results. While Noroi: The Curse does adopt this style on occasion, the majority of the movie is shot more cinematically and is presented as an unfinished documentary, which has been competently filmed by a professional cameraman. Shiraishi ensures the movie is realistic by fully committing to the documentary formula. The complexity and sheer density of the plot borrows from elements of Japan’s mythology of demons as well as a dark history of the country.

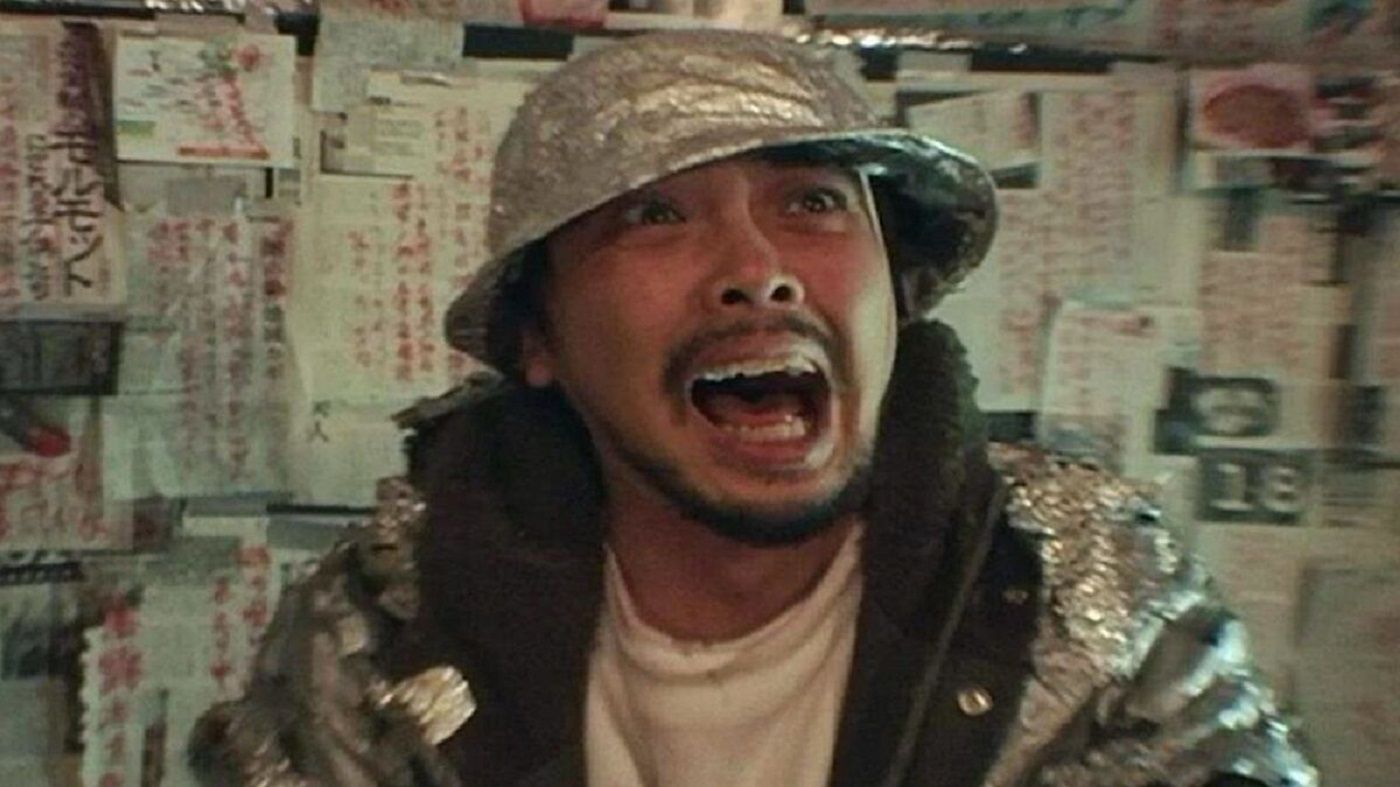

The primary antagonist in Noroi: The Curse is referred to as Kagutaba, a mysterious demonic figure who was mistakenly summoned during a ritual. Though entirely fictional, Kagutaba has been inspired by Japanese folklore and his appearance is reminiscent of characters from Noh theatre. The actual Kagutaba has little screen time in the movie, but his presence is felt in a deeply troubling atmosphere, which the movie establishes from the first minute. Noroi: The Curse also marked the first time Shiraishi established his own horror style, which was maintained in many of his subsequent found-footage movies. One of the most unusual, yet strangely effective scare tactics he adopted was freeze-framing. This technique is used occasionally in Noroi: The Curse. A scene will play out without any obvious abnormalities, the screen will then freeze, rewind, and direct the audience’s attention to something hiding in plain sight by slowly zooming in. This is to give the impression that the finder of the footage is analyzing the image before them.

This technique of freeze-framing was prominently used in Shiraishi’s Occult and Cult. Along with Noroi: The Curse, these three found-footage movie form an unofficial trilogy for their similar styles and themes. The same ghost fetuses appear in all three, too, and Shiraishi casts many actors as themselves in each movie including Marika Matsumoto and highly-regarded director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Shiraishi himself even has a key role in Occult, which is a more light-hearted found-footage horror movie with parodic tendencies. Both Occult and Cult relied heavily on special effects with apparitions forming directly before the audience. Despite the creative designs of the ghosts, due to limited budgets, the effects look cheesy but Shiraishi’s ambitious nature and comedic self-awareness give the movies enough freshness to entertain. The mockumentary approach to Occult and Cult is a mind-bending mashup of realism and surrealism, as Shiraishi goes in directions which seem ludicrous for the found-footage subgenre including to alternate dimensions.

Shiraishi’s latest found-footage outing came in 2014 with A Record of Sweet Murder. Elements from Noroi: The Curse, Occult and Cult are prominent still, but A Record of Sweet Murder is perhaps the most unique one of all. It is a real-time, one-take thriller which sees a cameraman (played by Shiraishi) and a South Korean reporter (Kim Kkobbi) being held hostage by an outwardly psychotic murderer (Yeon Je-wook) whose intentions are unclear. Despite all the limitations that come with found-footage movies, Shiraishi manages to create a horror film that’s as absurd as it is heartfelt. It unfolds like a stage play for the most part, but the second half in particular becomes bizarre and surreal.

True to Shiraishi’s style, it is ambitious and experimental in its execution, but it explores the untapped potential of found-footage movies to its fullest extent. It is consistently tense despite being dialogue-heavy with several long, seemingly nonsensical monologues from Yeon, yet it all adds up in the end with Shiraishi successfully delivering an unexpected twist. Typically, found-footage horror films end in disaster with the deaths of primary characters, but Shiraishi manages to avoid this cliché by exploring elements that really should not work in the subgenre. The unusually happy resolution to A Record of Sweet Murder is truly refreshing.

Shiraishi has also released several other found-footage films, which have become obscure, including Shirome, Cursed Violent People, Chō Akunin, and Ura Hora, all of which are difficult to find outside of Japan. His most positively received movies have found their way to international audiences and have amassed cult followings over the years. Whether he is striving for terrifying realism or ludicrous self-deprecation, Shiraishi has continuously proven himself to be outrageously versatile within the found-footage subgenre.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link

-1.jpg)