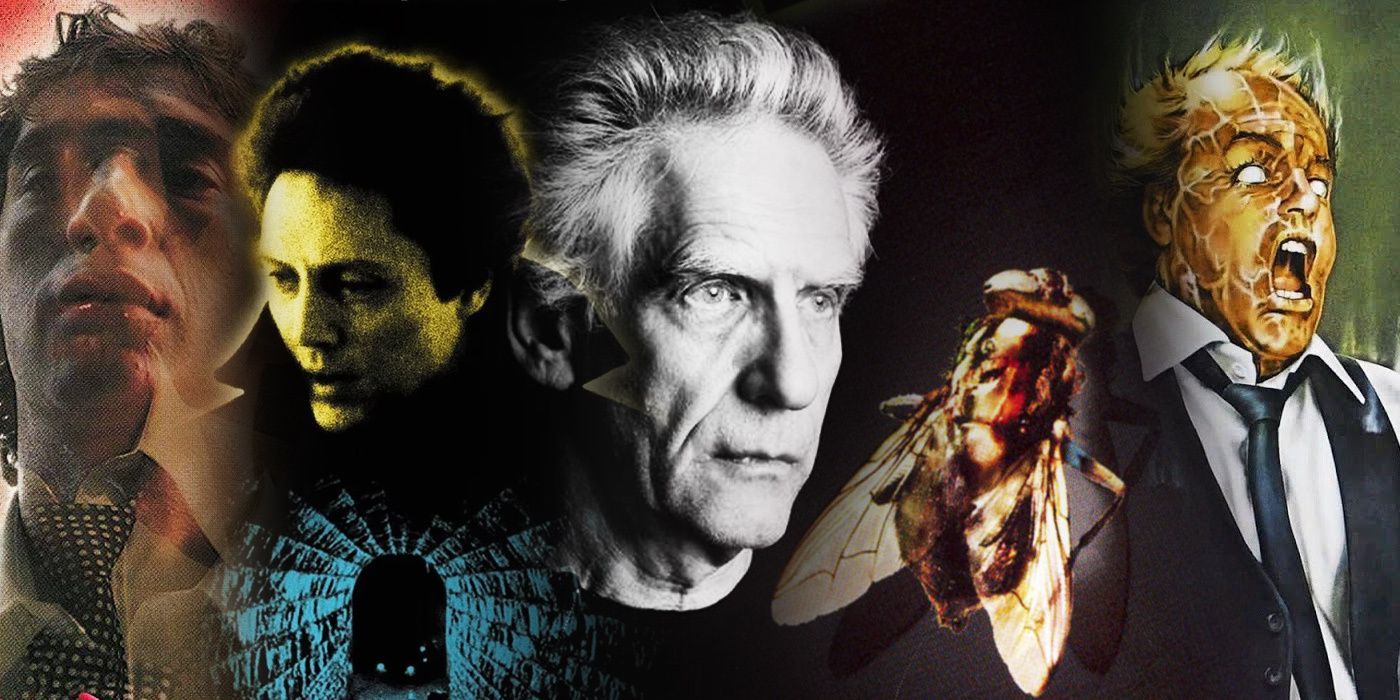

The works of David Cronenberg have become synonymous with grotesque transformations, often of the science-fiction variety. Pop culture properties ranging from the 2015 Fantastic Four movie to the TV show Rick & Morty have referred, either subtly or explicitly, to Cronenberg’s close attachment to this form of body mutilation. Nobody will deny that Cronenberg’s most famous works have often involved men vomiting up goop while being turned into gigantic flies or turning their stomachs into guns. However, Cronenberg’s affinity for showing how humans transform themselves is a touch more nuanced than just what’s seen in his most extreme sci-fi features. The works of this filmmaker have explored the concept of transformations in wildly varying ways, including ones deeply internal that are no less impactful and harrowing.

The varied manifestations of transformations may have become more prominently noticeable in Cronenberg’s 21st-century works. However, he’s always shown an affinity for keeping audiences on their toes regarding how this concept will appear in his films. In the 1980s, for instance, Cronenberg often turned to science-fiction storytelling to explore the ways human beings can grow and evolve, with such features involving heightened concepts like telepathic humans or people transforming into gigantic flies.

In this same era, though, Cronenberg also delivered Dead Ringers, a 1988 film about twins, each played by Jeremy Irons, who often assume the other one’s identity. This allows the more reserved twin, Beverly, a chance to exploit the social skills of the more outgoing twin, Elliot, in sexual situations, all without the participating woman’s consent. Here, transformations initially come in the form of Elliot and Beverly switching identities and names for personal gain. As the story goes on, Beverly is further transformed by his struggles with depression and addiction, a more grounded way to display how human beings can evolve to become drastically different individuals.

The story tragically ends with the disemboweling of Elliot at the hands of Beverly, all in a vain drug-induced attempt to “transform” their lives and ensure that Beverly can have an existence that’s singularly his own and no longer defined by being a twin. The use of addiction in Dead Ringers is a manifestation of transformation in an external form informed by a disease that neither twin can fully erase. This conclusion, meanwhile, is like the switching of identities at the start of the film in being a heavily misguided and self-inflicted form of transformation for personal gain. Just as lying to women only ends with these ladies being correctly enraged at Beverly and Elliot, so too does this attempt at transformation arrive at an inevitably grim endpoint.

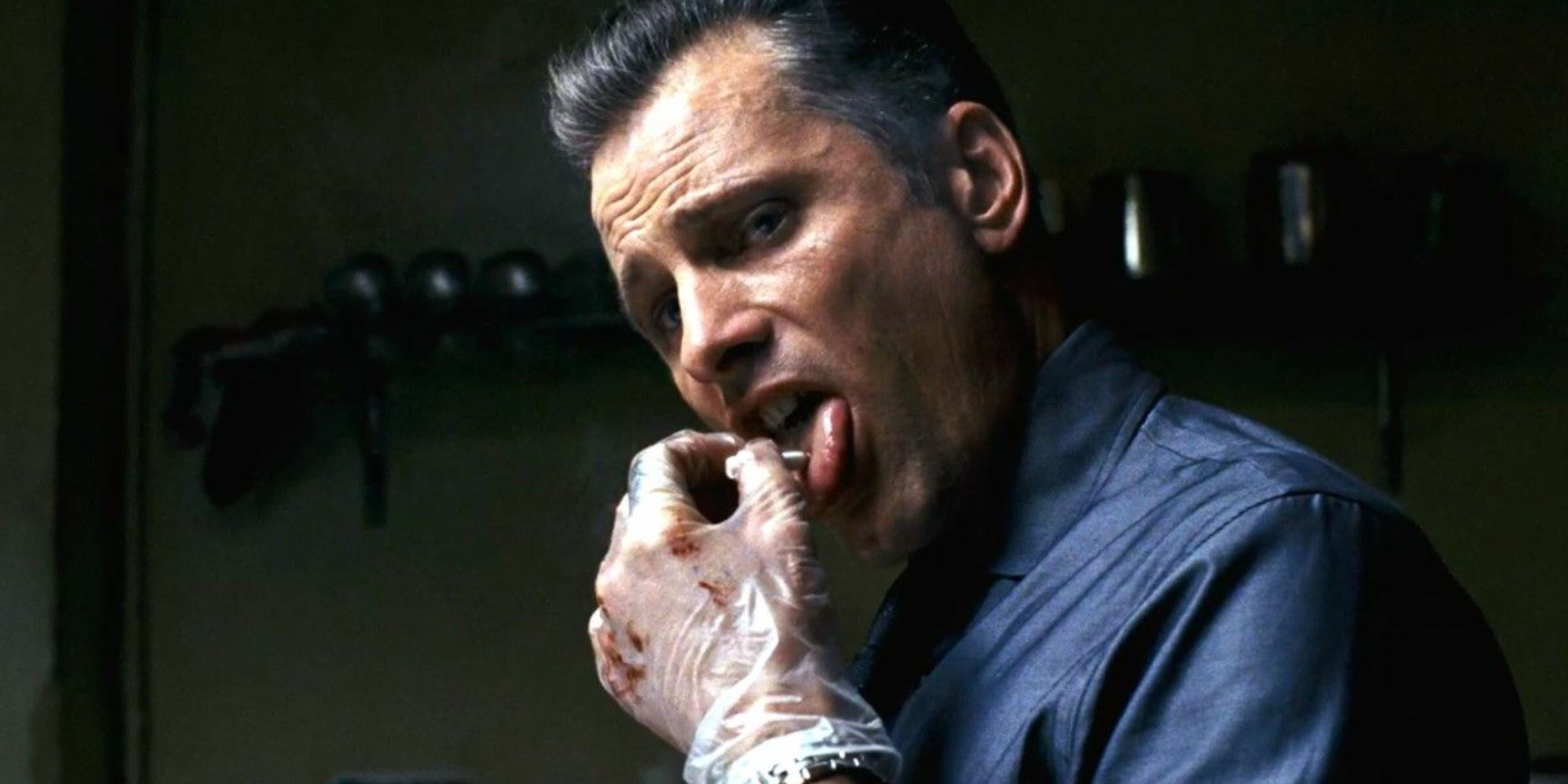

Cronenberg would further explore this line of grounded transformations in his 21st-century works, namely the 2005 film A History of Violence. Here, Cronenberg regular Viggo Mortensen plays Tom Stall, a man living quiet existence with his family in a small town in Indiana. When Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris) shows up at his house one day demanding to talk to Joey Cusack, the deception that Stall has built his life around begins to unravel. Now the truth comes out that this man is no mere diner owner. He’s actually a violent man with mob connections who decided to get a fresh start and leave this life behind.

While nothing from the domain of science-fiction creeps into A History of Violence, it’s easy to see how this fits with Cronenberg’s obsession with transformations. What’s especially interesting with this manifestation of this thematic motif, though, is that we’re not watching the transformation happen on-screen, like in The Fly or even with the slow crumbling of Beverly in Dead Ringers. Cusack has become fully comfortable in his Stall persona as A History of Violence begins. This is a story about the fallout from transformations, rather than the process of transforming itself.

Through exploring this fallout, screenwriter Josh Olson, adapting a graphic novel of the same name by John Wagner and Vince Locke, invites the audience to wonder if we can ever truly escape our past. Are human beings capable of transforming to the point that they can abandon transgressions of yesteryear or is that kind of dramatic change impossible? In other words, A History of Violence asks moviegoers to question how deep this transformation of Cusack goes. Is he really enamored with the life he’s made as Stall or is it all a cover just to escape the mobster life? These and other thoughtful questions lend a specific nature to how A History of Violence confronts the concept of transformation, especially within the context of Cronenberg’s filmography.

Further grounded explorations of transformations would be cinematically probed with Cronenberg’s directorial follow-up to A History of Violence, Eastern Promises. Here, an orphaned newborn becomes the centerpiece of a struggle between midwife Anna (Naomi Watts), Russian gangster Semyon (Armin Mueller-Stahl), and Semyon’s driver Nikolai (Viggo Mortensen). Here, transformations manifest through people making a conscious choice to intervene and help other people. When Anna first proposes to her mother the idea of helping this orphaned kid, her mom exclaims that ordinary people like them don’t get involved in these matters. To step out of line, to aid the helpless, would transform their lives to an adverse, uncomfortable, and even deadly degree.

While transformations in other Cronenberg’s movies have often been coded as negative, in Eastern Promises, the process of altering one’s life is shown to be something good. While Semyon clings to a status quo that benefits him enormously, the heroic characters of Eastern Promises are ones willing to take a risk, even if it means transforming their lives for the worst, in the name of helping others. Even Semyon’s son, Kirill (Vincent Cassel), gets a moment of quasi-redemption in the film’s climax. Here, he transforms himself from a henchman who’s unquestioning of his father to somebody who refuses to kill a baby just because Semyon said to. Despite being such a brutally grim movie, Eastern Promises functions as the more optimistic spiritual sibling to A History of Violence in showing a promising portrait of humans being capable of transforming for the better.

These richly human and complex portrayals of transformations are some of the most fascinating interpretations of this concept across Cronenberg’s massive and impressive body of work. Of course, other Cronenberg movies tackle this notion more in line with his pop-culture reputation, with plenty of guts, scares, and goo to make you scream. Titles like Videodrome are just as valid and artistically important as any in Cronenberg’s filmography, but they shouldn’t be seen as the only way this filmmaker explores the idea of how human beings can, for good and for ill, transform themselves.

![Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic] Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/9e7sW3TubFHM00yvXe5zvvbhAVriJiGqS8xmVFLPC6s/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zb2NpYWxfc3ByaW5nX2NsZWFuaW5nMi5wbmc=.webp)

![5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic] 5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/Hv-m77iIkXSAtB3IEwA3XAuouMwkZApIeDGDnLy5Yhs/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9saW5rZWRpbl9zdHJhdGVneV9pbmZvMi5wbmc=.webp)

![30 Quick Ways to Increase Your Website’s Conversion Rate [Infographic] 30 Quick Ways to Increase Your Website’s Conversion Rate [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/K2jxesa4VYrP9for8bLh1pb5V5Tu6SH1yzzlYw--8IE/g:ce/rs:fill:900:11471:0/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL2NvbnZlcnNpb25fcmF0ZXNfaW5mbzEucG5n.jpg)