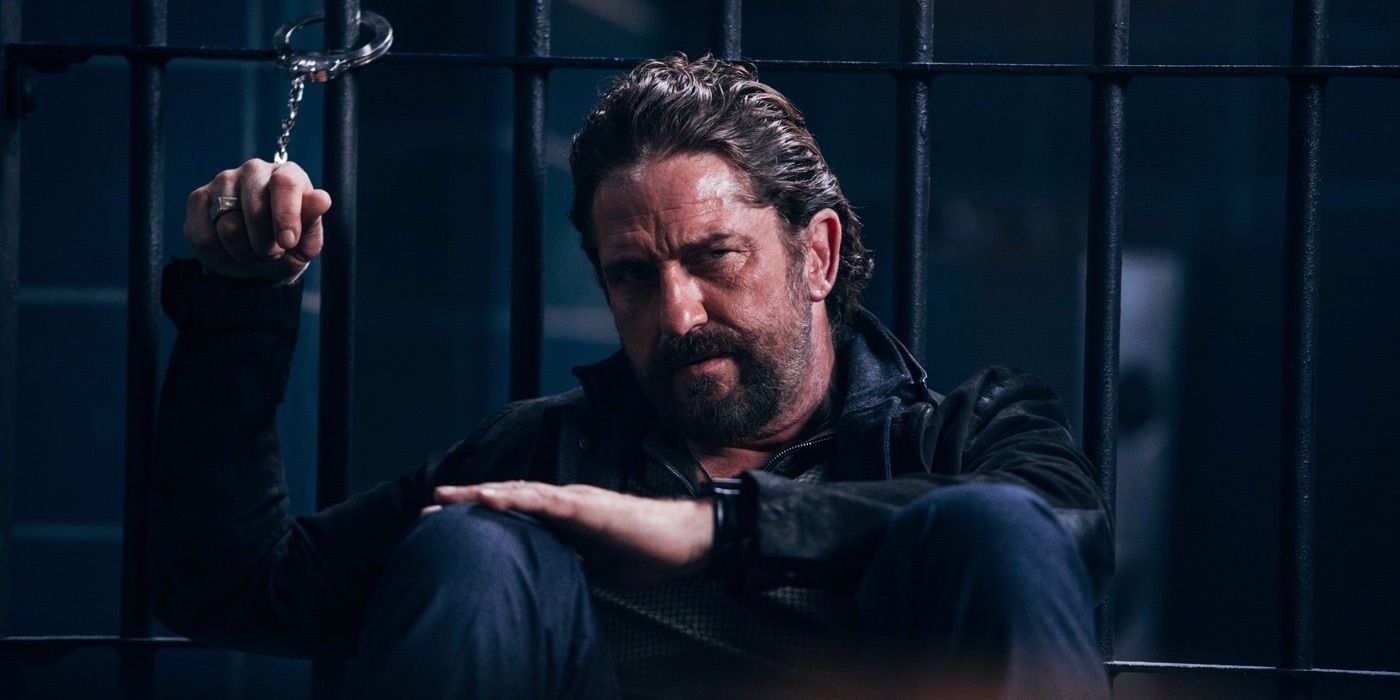

A new Gerard Butler action movie is occasion to celebrate. In fact, this year promises at least two Butler B-movies, so to speak: Plane and Kandahar. With Tony Goldwyn giving a wry smile in the trailer for Plane and saying of Butler’s character, “I like this guy,” it would appear that old action movie habits truly die hard and die harder. Twice-nominated for Worst Actor at the Razzies and winning for Worst Foreign Actor at the Spanish Razzies, Butler’s self-aggrandizement persists, positioning him as the inheritor of a long-fallen B-movie action star torch.

Gerard Butler Is Steven Seagal’s Action Star Successor

In the beginning of Above the Law, the main character is introduced with a black-and-white photo montage and voiceover. These are photos of the actor Steven Seagal, who’s effectively narrating his own life story, about moving to Japan and studying with the karate masters. This isn’t a movie with Steven Seagal, it’s a Steven Seagal movie – the very first! After a successful run through the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, his retreat to home video and then Russia coincided with the extinction of this type of movie. The action genre was eaten up by franchises in the 2000s. There may have been “Jason Statham movies” in that way, but as a screen presence, Statham is cool and understated. No, the Seagal successor is Gerard Butler. Despite what the critics say, he’s achieved an important place in cinema committing to an outdated tradition with an intensity both funny and honestly charming. He’s the perfect American action hero in an age that simply has no use for one.

Gerard Butler’s Road to B-Movie Action Stardom

Butler had experimented with a variety of roles, including the villainous Dracula, a sidekick’s sidekick in Reign of Fire, and even the Phantom in Phantom of the Opera, before his breakout with 300. The fantasy epic was a proper introduction to the actor, and just as much of a thesis statement as Above the Law. “This is Gerard!” indeed, a man whose own photo montage traded the dojo for the agōgē, where his character Leonidas trained by fighting a wolf to one day lead 300 Spartans into war against the Persian empire. If it’s been a while, 300 was basically structured like a video game, with Leonidas fending off increasingly difficult waves of enemies. Standard infantry? Done. Immortals? Straight wasted. Rhinos? War elephants? Please. All the while, back home, a snooty politician assaults Leonidas’s wife, and is revealed to be colluding with the Persians. That sickening half man!

300 established Butler as a permanent leading man, one of rippling, shouting masculinity. Only three years later, the film Gamer is deconstructing this new Hollywood icon – almost. The sci-fi thriller is a bone cruncher that’s aged remarkably well, removed from the context of an overcrowded subgenre – convicts forced into a death game – to where the dialogue isn’t a grim portent of things to come. It’s stylish and brutal; tactile, with sprays of rubble and gore caking the roving biceps of Kable (Butler) as he zooms toward the audience gun-first. This is Butler at his least mainstream while, ironically, directors Neveldine/Taylor were moving up the Hollywood ladder. Animated by the frenzied vulgarity of the Crank films, Gamer nevertheless depicts a good man trying to restore a nuclear family. Of course, this is no PG-13 vacation tour through Paris. Kable breaks a man’s spine over his knee (an impressively creepy Milo Ventimiglia, no less), and his escape from a garish Sims world is explosive and cathartic, decimating infrastructure along with the bodies. At the center of the ultraviolence is a Gerard Butler who fits like a glove. He doesn’t walk or run, he barrels.

Early in the film, he digs his fingers through white sand, and flashes of memory shoot through his mind. While every non-Seagal character in a Seagal movie monologues about how badass Seagal is, no such exposition serves Kable. Instead, we witness an absurd world through his eyes. All Butler has to do is react, however angrily, and he’s understood. It’s a nimble achievement of empathy with a character, or at least a simpatico, that becomes vanishingly rare in his filmography. Take Machine Gun Preacher as an example. Despite being about Sam Childers, who gave up his life of crime to protect children in Sudan from the Lord’s Resistance Army, the film jettisons the audience from the character’s headspace. What motivates these radical decisions? In the absence of anything else, one must conclude it’s something like “American values.” He wants to be a good man. Family man. A man of God. These are not complex ideas, and it’s movies like this that insist on an objective interpretation of what they mean.

Our understanding of Sam Childers is almost entirely constructed from who he isn’t. A female doctor who’d been working in Sudan tells him, “You’re a mercenary, not a humanitarian,” and she’s later attacked by LRA and rescued by Childers’s intervention. The Sudanese president John Garang meets with Childers at one point, but he’s never been mentioned before. The question arises: “Where the hell has he been all this time?” When Childers has to raise $5,000 for a desperately needed truck to ferry rescued children, he’s invited to a lavish home where a guy cuts him a check for $150. Greedy bastard! And a better question: “Why can’t Childers just be a good man?” Why does he have to be the better man? It’s the politician from 300 writ large, and repeatedly.

These movies thrive on hierarchy, with Butler always on top. Better in some way than everyone else, it’s the Seagal exposition without words. In Olympus Has Fallen, there’s the villain, given over to subterfuge and dirty tricks, the turncoat whose treason is resolved by a good ass-kicking, and the men in situation rooms whose efforts come up short. Butler plays Mike Banning, the square-jaw, verb-surname Secret Service agent who defeats or outperforms all of them in his mission to rescue the president from North Korean terrorists. Obviously absurd, it’s also a grotesque film which resorts to literal low blows to generate the indignant patriotic fury rationalizing Bannging’s response, including a scene where a terrorist beats an American female politician nearly to death. Well, however distasteful, it is effective. If the whole film wasn’t already “Die Hard in the White House,” this would be considered “cheating.” Blood is properly boiled, and the desire for justice or vengeance or whatever is so thick it could take a spear and shield to the Hot Gates.

Early in the sequel, London Has Fallen, Banning receives a rundown on the complex logistics of the British prime minister’s funeral, and when asked if he can make it work, he replies, “Always do, sir.” Damn right he does. There’s a strange comfort in the man who can take any complicated problem – security strategy, human beings – and reduce them. With the Has Fallen series, our distance from the Butlerian character is complete. Accessed via others’ awed perspectives, he’s dependable in any situation and appropriately outsized, which tends to surface his idiosyncrasies. In one scene, he says, “I don’t know about you, but I’m thirsty as fuck” before downing a tall glass of water and going “Ah.” What is this guy’s deal? And his one-liners are terrible. When a bad guy tells him, “Fuck you,” his response is, “Fuck me? Fuck you!” Elsewhere, he actually says, “Let’s get to the chopper,” and later, “I’ll be back,” without any winking irony. It’s like the ‘80s never happened, and the inherent sociopathy of one-liners is suddenly apparent.

Gerard Butler’s Delivers Generic Violence

Beyond Americanizing ancient Sparta, Butler’s violence has no foreign discipline like Seagal’s. In Gamer, it was generic brawling, with wide hooks. The flash of a bicep and it’s lights out. Banning shows a hint of MMA here and a little gun fu there, but he evinces as much style as the whole of London Has Fallen. Its one-take action scene – always impressive – has no narrative context or sense of escalation. It isn’t a movie for people who obsess over such “film” details, or feel a warm sense of community at throwback references. Instead, these movies are for everybody, as the box office attests, led by a hero who’s strictly business. He takes the quickest route to every problem, as anyone in the audience can imagine themselves doing.

Of course, presuming the thoughts and demographics of the audience is what makes Machine Gun Preacher and the Has Fallen series make Gamer look unproblematic with the former a textbook white savior movie. Gerard Butler holds a dying African child in his arms as the camera hovers above him; if only he was wailing “No!” but perhaps the arc of history bends toward progress. In response to London Has Fallen, an opinion piece in The Guardian accused the film of “[denying] the locals a convincing voice in the face of terror attack. It doesn’t care about the city it’s destroying.” This is a remarkable takeaway from a film that opens with a drone strike obliterating a wedding in Pakistan. In fact, a shouted line of dialogue insists that London can’t turn into “another Fallujah.” At least “London” doesn’t connote just one thing.

Gerard Butler Movies Are a Good Time

It begs the question, what does Gerard Butler think about when he’s involved in these movies, not only as the star but often as producer? Is he defensive? Does he shout? No. Watch any of Gerard Butler’s interviews, and it’s the portrait of an infectiously enthusiastic actor. He clearly loves his job, and he’s proud of his work. Not to invoke Keanu necessarily, but he’s one of those stars who remembers the names of stunt doubles and even an animator on How to Train Your Dragon. This puts him far ahead of Steven Seagal, who was so reviled in Hollywood that the producers of Exit Wounds allegedly conspired to have Michael Jai White put him in the hospital. If anything, the Gerald Butler movie is a good time. He’s having a laugh, we’re having a laugh.

London, Sudan, Jolo, Kandahar, these are interchangeable backdrops. Any specific criticism is rendered null by its copy/paste into the next one. The whole world is terrifying, and men like Mike Banning protect us from it. With complicated real-world problems and political relations simplified for resolution by means of a gun, it’s all so absurd that it’s best called escapism. And granted, American audiences shouldn’t require their escape be so xenophobic. As an actor, though, Gerard Butler is better served by roles untempered by Hollywood morality, and an honest American hero is one lost within layers of fantasy and self-mythologizing: easily detected and easily ignored, but where’s the fun in that?