While much has been written on the pop culture power and musical prowess of Elvis Presley’s 1968 Comeback Special and the subsequent concert films surrounding The King’s Vegas Years, the Golden Globe-winning documentary Elvis on Tour sees the titular singer transcend his contractual obligations to tour America again, delivering on the promise of his earlier career after a decade of Hollywood acting and a seemingly endless cycle of contractual performances in Las Vegas. Filled with split-screen footage of emotional performances across the country, Elvis on Tour formally fragments Elvis to highlight the transitional state between his career peak in the late 1960s and eventual decline in the late 1970s, foregrounding the humanity of Elvis Presley in every frame. Boasting a bold roster of talent off-screen including cinematography by prolific camera operator Robert C. Thomas (In Cold Blood, Stop Making Sense) and expert editing by Ken Zemke and Martin Scorsese, Elvis on Tour pushes beyond the typical concert film formula to encapsulate a multi-perspective meditation on the man behind The King.

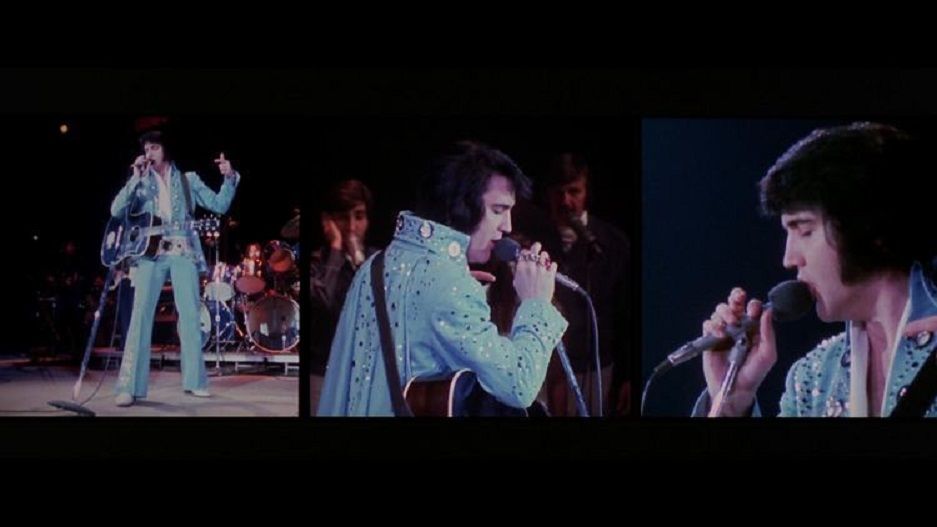

From the opening sequence of Elvis on Tour, veteran concert documentary directors Robert Abel and Pierre Adidge establish the film as a private view into the emotional vulnerability of Elvis Presley, focusing on a quiet moment between The King and his entourage backstage before the first show of his 15-city tour. Punctuated by Elvis’s back-and-forth pacing and a voice-over expressing his perpetual nervousness in regard to performing live, Elvis on Tour boldly eschews the heroics and histrionics of celebrity-centric documentaries by placing the audience within the mindset of its subject. Even as this scene superficially appears to be a brief prologue for the glamorous jumpsuit-clad performances to come, the backstage sequence of Elvis Presley’s mental preparation for his concert functions as a tonal key to the rest of the film, pointing the audience toward the interiority captured in the kinetic split-screen sequences. As the orchestral swells of Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra” overtake the soundscape in order to prepare for The King’s arrival on-stage, editor Ken Zemke juxtaposes images of Elvis’s final moments backstage at three separate concerts in split-screen, emphasizing the repetitive rhythms of touring as well as the daily toll of Presley’s work.

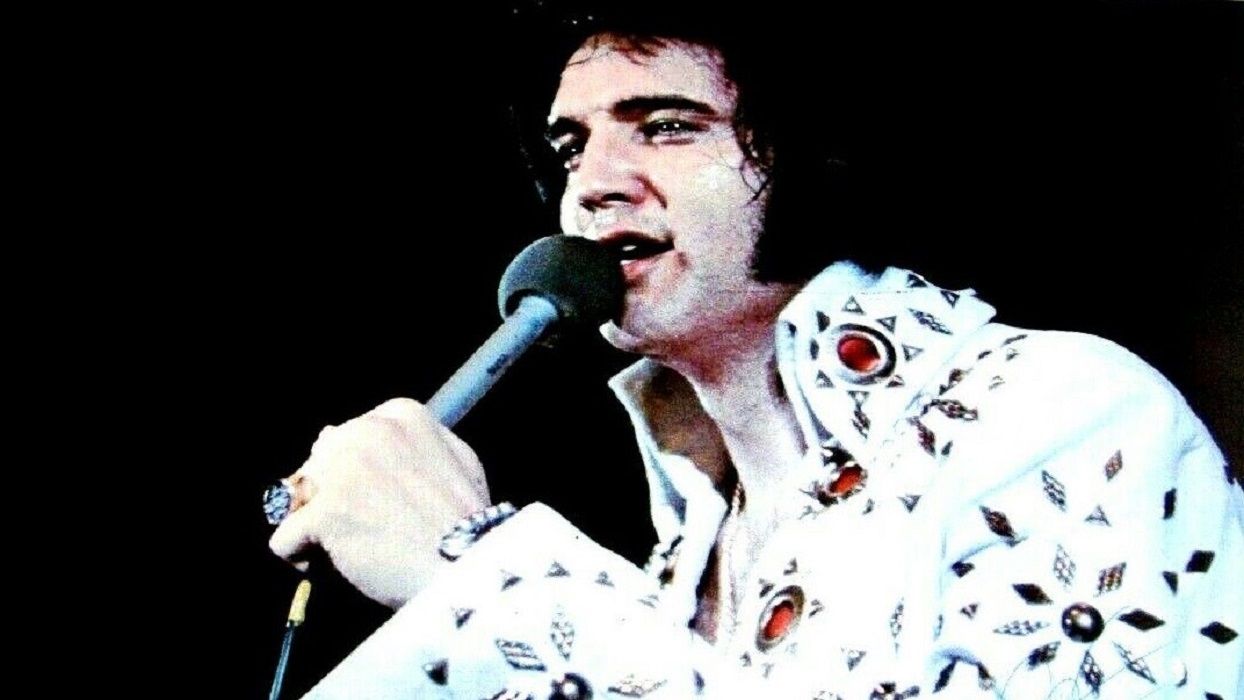

In the midst of the energetic live performances that comprise the bulk of Elvis on Tour, cinematographer Robert C. Thomas employs impressive improvisatory camerawork to capture moments of humor and heart within the extended musical sequences. From the slight giggles and gestures toward his bandmates that permeate the effortless cool of “See See Rider” in the opening sequence to the air guitar antics at the center of “Polk Salad Annie,” Thomas’s vision of Elvis is centered on The King’s playfulness and the joy of his collaborations with his touring band as well as his accompanying vocalists. Even as The King maintains his undeniable star power in every performance throughout the film, Elvis’s charming communal presence uncenters his sole talents to place his fellow musicians and vocalists on even ground, emphasizing Presley’s humility at the height of his fame in conjunction with his naturally introverted inclinations. In particular, Elvis on Tour features an early performance of the hit single “Burning Love” in which Elvis confesses to the newness of the track and apologizes in advance for possible mistakes. As the song progresses, Thomas allows the multiple cameras to linger on the growing confidence between Elvis and his collaborators, focusing on the growing smiles of The Sweet Inspirations and The Stamps as they sing backup vocals as well as Elvis’s increasingly limber dance moves. Through the triple-screen format of his cinematography, Thomas emphasizes the collective power of performance through observational footage, focusing on the entire band in conjunction with Elvis in a similar manner to his future collaboration with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth on the Talking Heads concert film Stop Making Sense.

Although the majority of Elvis on Tour hones in on capturing Presley’s physical and emotional experience through contemporaneous footage, the film features a fascinating detour into Elvis’s early career, which was compiled and edited by cinematic icon Martin Scorsese. Opening with an evocative match-cut between a tired 1972 Elvis riding between venues with his entourage and a photograph of a young Elvis riding a train with a record player in his lap on his first tour, Scorsese’s mid-film montage provides both historical context and tonal continuity for the picture’s naturalistic meditation of the state of Elvis Presley in the 1970s. Scored by an instrumental rendition of “Don’t Be Cruel” that pivots effortlessly into Elvis’s live performance of the same song and “Ready Teddy” on The Ed Sullivan Show, the retrospective montage provides an extra layer of humanity to the film’s investigation of Elvis, reminding the audience of the young musical revolutionary and cultural touchstone who became the jumpsuit-wearing rock star still touring to nationwide acclaim two decades later. Mirroring the split-screen style of the rest of the film, Scorsese’s montage of early Elvis moments highlights the outrageous reactions and emotional responses of young women to Elvis’s foundational performance style, suggesting Presley’s influence on the sexual revolution and music-driven counterculture of the 1960s.

Beyond the montages and meticulously edited split-screen performances, perhaps the most powerful moments of Elvis on Tour are the quiet asides of Elvis’s own observations. From the silent stares that fill close-ups in the traveling sequences between venues to the extended emotional aside of Elvis crying and listening while The Stamps perform “Sweet, Sweet Spirit” at his arena show in Houston, many of the most human moments on-screen now appear equally haunting and hopeful within the framework of Elvis’s larger story. Although the various vulnerable observations showcase his slow decline in the midst of grappling with the cost and consequences of fame, each shot of Elvis also reveals his humanity and complexity, stripping away the pop cultural mythology to reveal an artist attempting to channel his talents into positive expression and maintain personal health and familial unity in the midst of a relentless schedule. Although Elvis’s tragic trajectory often overshadows the latter-day highlights of The King’s career, Elvis on Tour serves as a beautiful and empathetic window into Elvis’s emotional complexity, undying love for his fans and fellow musicians, and the groundbreaking talent that he brought to the stage night after night.

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)