How about the recent plethora of strong recent horror films bearing cryptic one-word titles? Shudder has its share, and A24 have certainly produced a slew of fine examples (Hereditary, Men, Lamb, Midsommar) over the last several years. Caveat, a nerve-shredding exercise in paranoia and mounting unease, can easily be considered one of the finest, most restrained European horror films of recent years, and it deserves to be placed alongside other recently revered fright-fests. Through the film’s delicate treatment of pain mixed with amnesia, as well as the subsequent mind games that can come with the inadvertent suppression of past horrors, Caveat is a truly terrifying experience that reveals its secrets with an almost musical cadence. For while many other great films of the genre have ventured down similar terrain to channel psychological horror, the claustrophobia and uncanny location on show in Caveat seem to magnify the utter bewilderment of its tortured protagonist.

Isaac (Jonathan French) is a haunted man who has apparently re-emerged from a kind of existential wasteland bearing a spotty memory as the result of a mysterious “accident.” Devoid of hope and seemingly without kin, he is also afflicted with the gnawing pangs of pitiful desperation. Approached by Moe Barrett (Ben Caplan), who claims to be his friend or at the very least acquaintance, he asks whether Isaac would be up to traveling to a remote, island-situated home to care for his psychologically disturbed niece. With her father (Moe’s brother) and mother also out of the picture, she is especially in need of “company.”

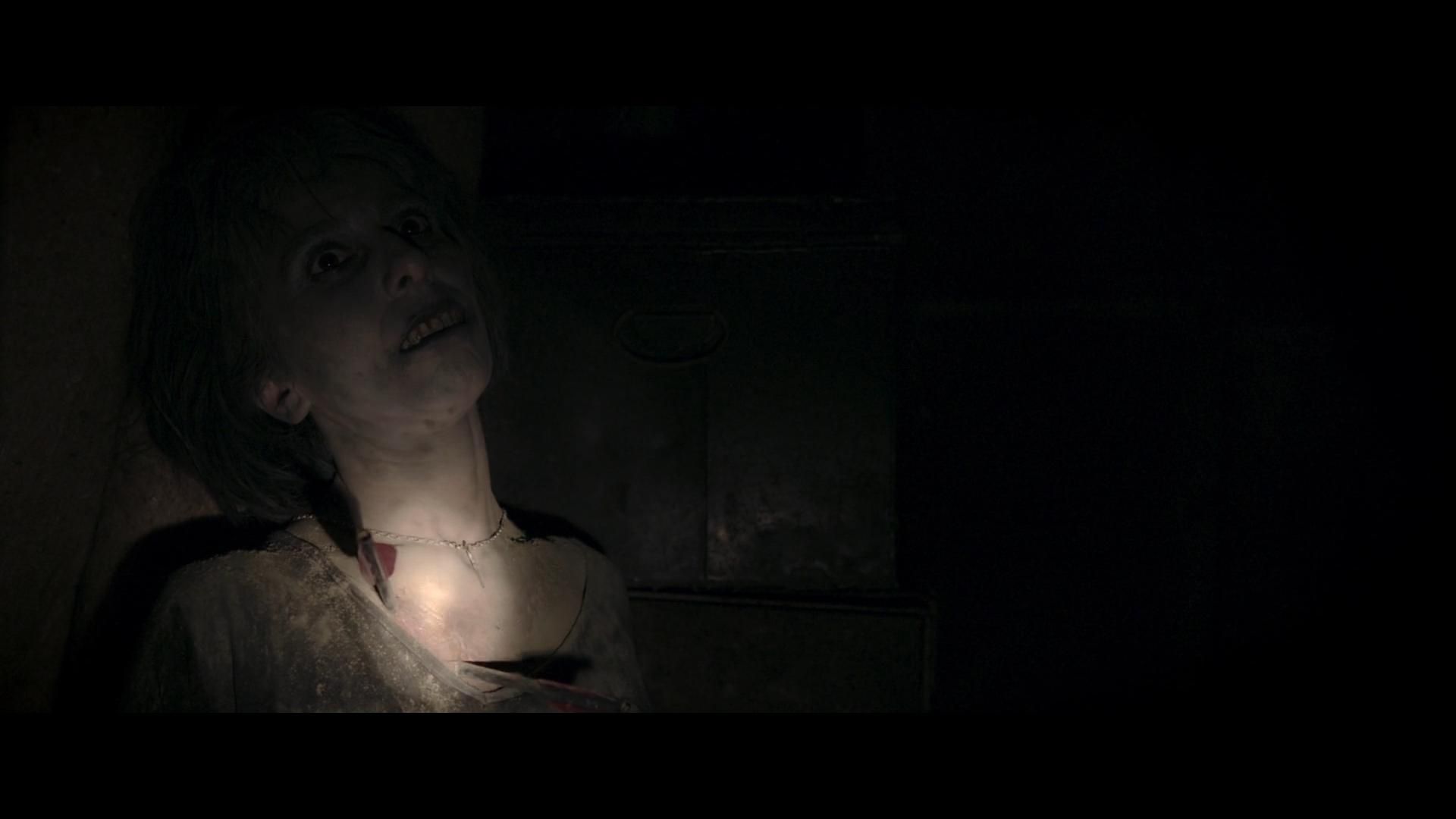

The opening conversation follows a brief sequence wherein an entranced woman wanders through a darkened house brandishing what might be the creepiest looking wind-up toy ever to appear on film.The title card arrives, and it isn’t a moment too soon, as Isaac says “There’s got to be more to it than that?” after considering Barrett’s odd proposition. It’s a quality opening that leverages two opposing images to denote the gulf between the real and the imagined, as well as the simultaneous distance and closeness between two separate sets of events.

The Cleverness of the Conceit

The title is suggestive of warning, and carries an implication (in a legal sense) that anyone entering into a transaction should be fully aware of both risk and reward. It hints at the nature of contract – in that both involved parties should adequately weigh up consequence and gain before committing to a mutual agreement. Isaac is untethered and damaged, and despite some initial apprehension, accepts Moe’s offer meekly. He appears to be completely bereft of possessions and carrying a mental blank slate. All the tenses (past, present and future) seem to be of little to no consequence anymore. The only lukewarm attempt he appears to make to try and salvage those flickers of unremembered short term experience occur via glancing at an old photograph he carries around. He frequently says he “can’t remember,” but the distinct impression given off is one of utter defeatism, as if the will to at least try and recall what was dear to him is non-existent. There’s a flowing undercurrent of existential sadness and futility that seeps into the atmosphere of the film, and it ends up being disarming for the viewer considering what’s to come.

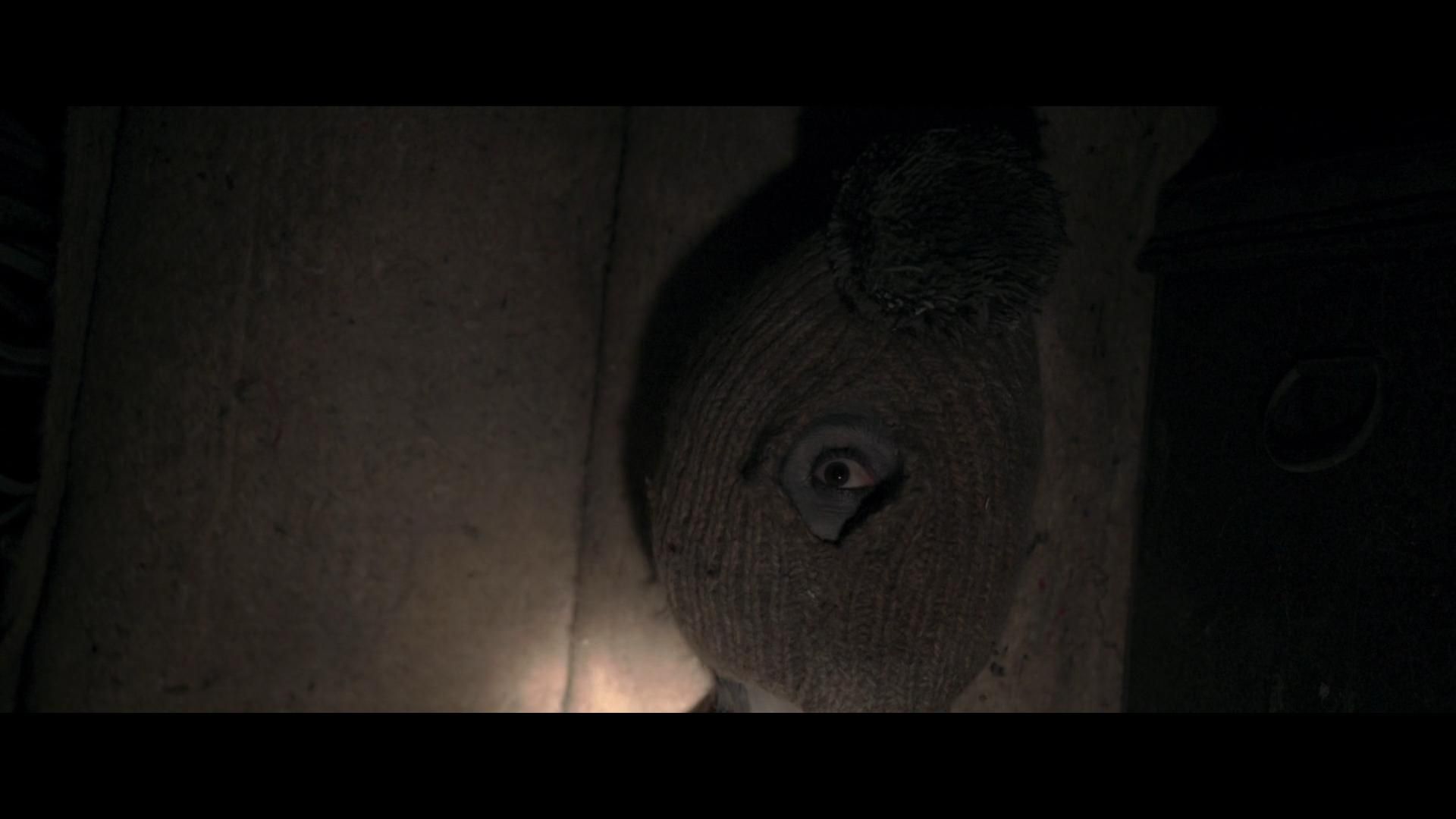

Director Damian McCarthy, in his first feature, draws upon the terrifying notion of surrendering identity expertly. In those drawn out sequences where Isaac appears to be idling the sunlight hours away before a movement within the house interrupts, a burgeoning sense of isolation arrives. Unlike 90s classics Jacob’s Ladder and Memento however, which both use the ruptured memory plot device to create labyrinthine mind-teasers, Caveat views the damage memory loss can do to one’s self-worth as something that resides on the fringes. It bullies the protagonist, impressing itself gradually on the terror that unfolds within the crumbling structure. Upon arrival, after accepting the “babysitting” job, Isaac is forced to wear a sleepwalking restraint, which effectively moors him to the building and disallows him from entering certain rooms. Despite initial protestation to something so utterly absurd, he accepts – and when the niece Olga (Leila Sykes) turns up unexpectedly during one of her “fits” (wherein she sits still with her hands covering her eyes) there comes an overwhelming sense that Isaac has a predisposition towards simply sitting out suffering.

Middle of Nowhere, Denial and Symbolism

Set and shot in rural Ireland, the locale itself is as adrift and forlorn as its wayward antihero. Repeatedly Isaac denies knowledge of things. When Barrett brings him to the island, Isaac complains of not being told this, despite the former saying he was pre-warned. When asked if he knows what a crying fox sounds like, he claims he doesn’t and is dismissive of the claim that the sound is chilling; akin to that of a crying teenager. When pressed on the matter of him possibly having been there before by Olga, he asserts he hasn’t. Utterly resolute in his world of denial and pain, the dark doings of the past year begin to inevitably clamber out of his mental pit of obscurity.

The house itself is dilapidated and permanently hued in dark, earthen colors. Confounded by various discoveries he makes at the homestead – including artifacts such as the aforementioned toy rabbit which begins to randomly emit its rhythmic drumming sounds without warning – Isaac’s guard slowly begins to slip. The mangy plaything, representative of an innocence corrupted. It soon occurs to Isaac that Olga’s mother’s (missing) fate may have been grisly, as imprisoned secrets waft up and through the cracked and worn walls via odd sounds and the discovery of a partially mummified body in the cellar. It’s then when he decides to infiltrate Olga’s room, defying instruction, to gain access to the only phone to tell Barrett. The set design works extraordinarily, mirroring the patchy, unkempt state Isaac has found himself in – utterly lost at sea.

The Pain of Realization

Once the now lucid Olga begins to divulge her family history (including further hints into the cruel fate of her vengeful mother) and maintains Isaac was involved in something untoward at that very house a year before, the traumas of his pre-accident life begin to rise from the depths. Upon fresh realization that Barrett may have hired him to premeditate the fate of Olga’s father in a hitherto compartmentalized incident, Isaac (injured as the result of an attack) crawls through the lightless house looking for sanctuary. Flitting between the oppressive darkness of his present reality and a series of ironically sunny images from the previous year that flood back to him in a stream of guilt and shock – he begins to accept that his own obstinate front is what has once again landed him as a pawn in an unforgiving and terrifying game. His own repression had contributed to his downfall.

Now starting to grasp at the straws of his murky prior history with Barrett, Isaac is charged with a semi-renewed determination to save himself. In what amounts to one of the single most frightening final 15 minute passages committed to tape involving a potentially reanimated cadaver and posthumous revenge – a literal and figurative escape beckons for the mentally and spiritually imprisoned Isaac. It’s a combination of pathos through unresolved pain and dormant fears, as well a creeping beyond-the-grave comeuppance that renders Caveat one of the most chilling forays into the genre, period. Untended wounds peck at the essence of one’s being. The ending is an eye-watering nightmare – something that most certainly will not be forgotten too soon.