David Cronenberg is coming off an eight-year hiatus with Crimes of the Future, a high-concept dystopian thriller in which pain is a relic and “surgery is the new sex.” Cronenberg pivoted to gritty adult fares like A History of Violence and Eastern Promises for the better part of the previous two decades, but Crimes of the Future promises a glorious and unabashed return to the director’s roots in body horror and science fiction.

In tandem with Cronenberg’s evolution as a filmmaker, the subgenre — indelibly influenced by Cronenbergian classics from the ‘70s and ‘80s — has also changed. Is there still a place for the Father of Body Horror among the New Flesh? That’s a question his latest will have to answer when released in June. In the meantime, there’s no better way of preparing yourself for Crimes of the Future than diving into examples of the kind of cinematic experience Cronenberg helped define.

‘Candyman’ (2021)

The Jordan Peele-produced “legacyquel” to the 1992 classic was one of 2021’s most anticipated films. It premiered to mostly positive reviews and announced Nia DaCosta as a major talent. The movie follows Yahya Abdul-Mateen II as a painter whose physical appearance and creative output are dramatically and horrifically altered by personal and collective cultural traumas.

Both Candymanand Crimes of the Future use horror as a vehicle to explore social themes and are about artists who sacrifice their bodies for their craft. In Crimes, poverty has forced some to adapt in ways that include eating plastic. Candyman similarly addresses how communities are shaped by inequality and environmental circumstance.

‘Crash’ (1996)

Despite the film’s copious sex scenes, Crash is one of David Cronenberg’s tamer movies. There’s very little in the way of gore or science fiction, but because it serves as a sort of meta-commentary on the auteur’s career, the movie has some thematic DNA in common with Crimes of the Future. At least two moments take on new meaning given his new project’s subject. The first involves a reenactment of the car accident that killed James Dean, and the second is a conversation between James Ballard (James Spader) and Dr. Robert Vaughan (Elias Koteas) — the latter casually muses on topics like the “reshaping of the human body by modern technology” — that tries to explain why someone would find that kind of destruction arousing.

“The car crash is a fertilizing rather than a destructive event, a liberation of sexual energy…to live that, that’s my project,” Vaughan declares. “What about the reshaping of the human body by modern technology? I thought that was your project,” Ballard asks. Vaughan replies: “That’s just a crude sci-fi concept that floats on the surface and doesn’t threaten anybody. I use it to test the resilience of my potential partners in psychopathology.” Whatever that exchange may suggest about Crimes of the Future, film majors writing theses on Cronenbergian cinema will be unpacking these connections for a while.

‘Crimes of the Future’ (1970)

If you want to walk into Crimes of the Future having really done your homework, check out the other Cronenberg-directed Crimes of the Future. While his latest is by no means a remake or a sequel, it has more than just a title in common with this peculiar film from 1970. Set at a dermatological clinic called the House of Skin, the movie addresses novel organs, humankind’s oceanic origin, and how chemical products alter DNA.

Different images and bits of dialogue can be connected to later Cronenberg films (for example, Dead Ringers begins by describing how aquatic life procreates), which is why it’s always fun to revisit a director’s early work. There are even references to the body being a microcosm of the universe, which have a similar ring to lines like Lea Seydoux‘s: “Let us not be afraid to map the chaos inside; let us create a map that will guide us into the heart of darkness.” The new Crimes of the Future sounds like his fullest realization yet of the evolutionary themes that were already evident in this hour-long, experimental feature he’d made at the beginning of his career.

‘Dead Ringers’ (1988)

Crimes of the Future certainly isn’t Cronenberg’s first time framing surgery as both a performative and artistic act. Besides Crash, Dead Ringers is probably the best articulation of Cronenberg’s thematic interests. Jeremy Irons plays twin gynecologists, Beverly and Elliot Mantle. Their personal and professional lives are threatened when Bev falls in love with Sophie (Geneviève Bujold), a patient with a rare anatomical mutation.

The fetishization of anomalous biology seems like an apt summary of Crimes of the Future. When Bev tells Sophie he’s always thought there should be beauty pageants for the insides of bodies, Cronenberg is conceiving the dystopia it’ll take him another thirty-four years to realize on screen.

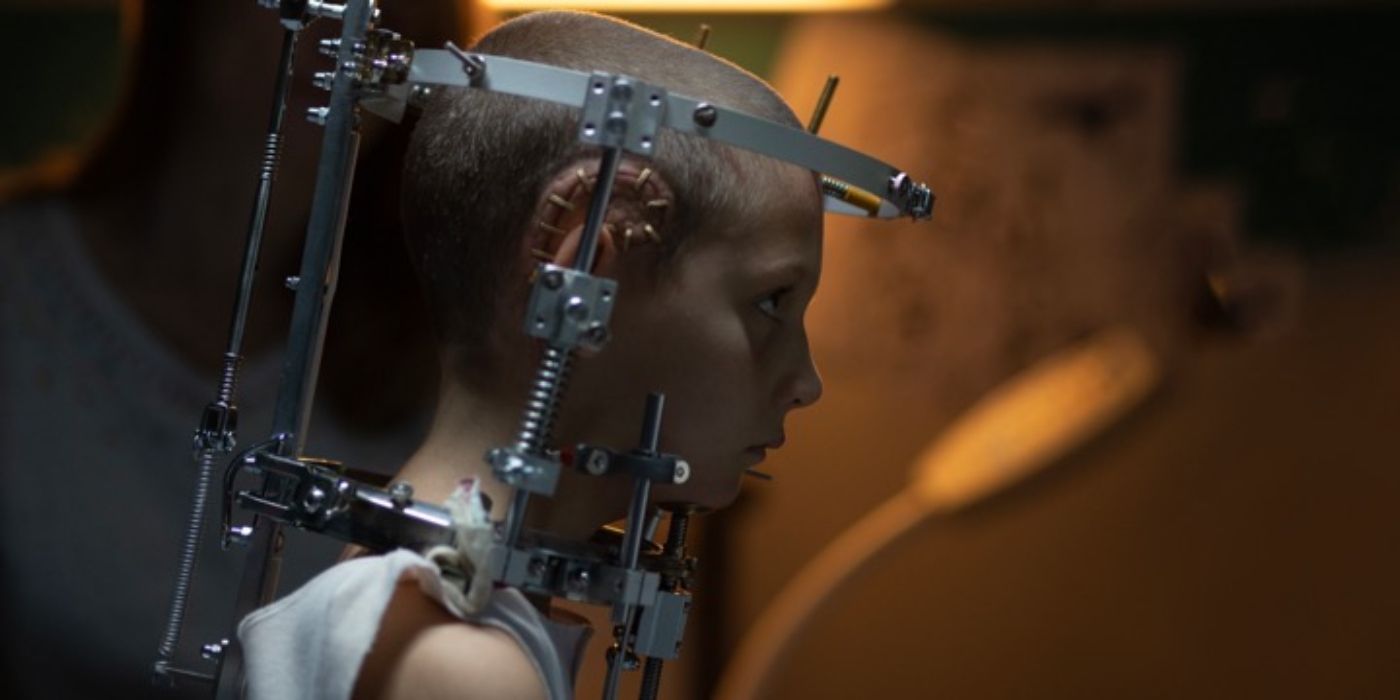

‘Elysium’ (2013)

Neil Blomkamp’s follow-up to District 9, a sci-fi thriller about a physical transformation gorily reminiscent of Seth Brundle’s in The Fly, ventures further into Cronenbergian territory. Set in a world where the poor must illegally board a space station for the elite to receive medical care, Elysium follows Max (Matt Damon), a factory worker who loses his job after being exposed to a lethal dose of radiation. His only shot at survival turns him into a kind of reluctant Robin Hood. At the behest of hackers who outfit him with a weaponized exoskeleton, he must infiltrate the ship and make it accessible to all who need its services.

Elysiumand Crimes of the Future are set in a future rocked by natural disasters and address themes like evolution and social inequality. The aforementioned scene of a mechanical spinal column being drilled into Matt Damon’s skull will likely make you squirm as much as anything you see in Cronenberg’s newest film.

‘Fresh’ (2022)

A hit at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Fresh is a slasher-comedy about modern dating and exploring the relationship between bodily trauma, sex, and art. If you’re having trouble wrapping your mind around Crime of the Future’s surgery-as-erotica concept, Fresh is precisely the fun point of entry you require. Sebastian Stan’s Steve, a character who wouldn’t feel out of place in a Cronenberg film, destroys the body in the name of an artistic calling (in his case, fine dining), much like Elias Koteas’ autofetishist in Crash.

Fresh’s connection to Cronenberg’s filmography may be tenuous, but the comedy’s accessibility should prepare you to see these themes in a darker light in movies like Dead Ringers and Crimes of the Future.

‘Possessor’ (2020)

Crimes of the Future is a fitting alternative title for Possessor, the second feature-length film from David’s son, Brandon Cronenberg. Much of this movie, featuring technology permitting assassins to possess people’s bodies with proximate physical access to their targets, plays like a hard-R Inception.

Brandon has his father’s knack for crisp close-ups and steady framing. In this movie’s ideas about multiple consciousnesses fighting for control of the same corporeal vessel, it recalls Cronenbergian classics like Scanners, Dead Ringers, and even A History of Violence. And, of course, there’s the gore, which Brandon Cronenberg punches up to an eleven with some gruesome imagery that will please and stun even the most extreme body-horror fans.

‘Titane’ (2021)

The marketing for Crimes of the Future has heavily focused on humanity’s adaptation to synthetic environments, given Cronenberg’s fascination with the “reshaping of the human body by modern technology.” That concept was recently taken to new heights by Julia Ducournau with 2021 Palme d’Or-winner Titane, which, as your friends have probably told you, is about a serial killer who procreates with an automobile.

Cronenberg’s reputation as the Baron of Blood precedes him, but an undeniable streak of sentimentality permeates his work. Think of Seth and Ronnie’s tender romance in The Fly or the affection Bev and Ellie share in Dead Ringers. Titane pulls off a similar blend of wholesomeness and brutality. The movie is just as strange as its premise suggests, but it’s also a heartwarming story about makeshift families. That tonal balance and the film’s transhumanist themes make it a must-see for anyone interested in checking out Cronenberg’s latest.

![Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic] Social Media Spring Cleaning [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/9e7sW3TubFHM00yvXe5zvvbhAVriJiGqS8xmVFLPC6s/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9zb2NpYWxfc3ByaW5nX2NsZWFuaW5nMi5wbmc=.webp)

![5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic] 5 Ways to Improve Your LinkedIn Marketing Efforts in 2025 [Infographic]](https://imgproxy.divecdn.com/Hv-m77iIkXSAtB3IEwA3XAuouMwkZApIeDGDnLy5Yhs/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/Z3M6Ly9kaXZlc2l0ZS1zdG9yYWdlL2RpdmVpbWFnZS9saW5rZWRpbl9zdHJhdGVneV9pbmZvMi5wbmc=.webp)

.jpg)

.jpg)