[ad_1]

It’s an essential part of the human condition. If you had no fear, you’d be dead by now. If your ancestors had no fear, you never would have been born. A healthy level of fear keeps us from walking out in front of oncoming e-bikes, getting eaten by dangerous animals, and swimming near rocks in a roiling ocean. Taken to an extreme, an unhealthy level of fear can keep us from going outdoors, from meeting new people, or from speaking up in meetings.

It’s an essential part of the human condition. If you had no fear, you’d be dead by now. If your ancestors had no fear, you never would have been born. A healthy level of fear keeps us from walking out in front of oncoming e-bikes, getting eaten by dangerous animals, and swimming near rocks in a roiling ocean. Taken to an extreme, an unhealthy level of fear can keep us from going outdoors, from meeting new people, or from speaking up in meetings.

In an article on the positive benefits of fear, Andrew Colin Beck coined the term EuFear, for “positive fear” (eu being the Latin prefix for “good” or “positive”), building on the work of Hans Selye, who originated the concept of eustress in 1974.

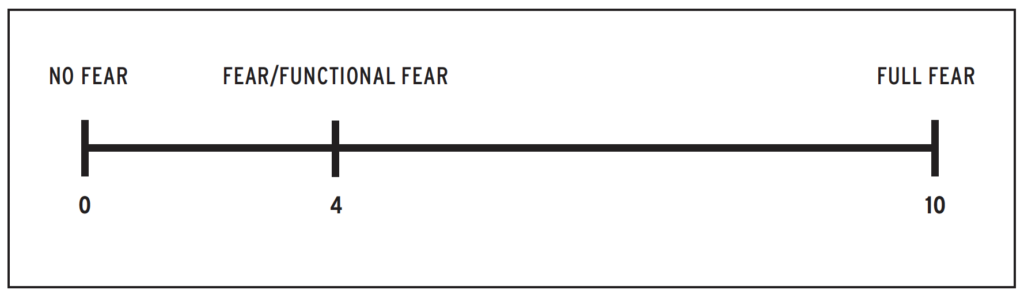

Selye argued that there is a positive cognitive response to stress that is healthy and gives one a sense of fulfillment and focus. Similarly, Beck suggests that we need a new paradigm for fear as well, one that looks at the benefits of fear, not only the negative effects. His model reframes fear as a motivator and proposes a fear continuum ranging from no fear to full fear, with EuFear being the desired functional state.

When there is no fear in a company, people aren’t motivated to do much at all. With no consequences for inaction and nothing to lose, people often don’t take risks or initiative. In contrast, teams that are working at full fear often experience crippling declines in performance. What’s more, living in a nonstop state of full fear can cause unwanted physical effects, such as increased heart rate and lower oxygen levels.

Beck’s model suggests that neither no fear nor full fear are ideal. Instead, his research indicates that the ideal for functional fear is at a 4 out of 10, slightly to the left of middle. It is at this point on the continuum that people experience fear that is positive and actually helpful in maximizing performance.

Leading with the Right Amount of Fear

Leading with the Right Amount of Fear

How does this idea of using fear to improve performance apply to leaders in the corporate world? When does fear cross the line from being positive to having a negative impact? When does fear become destructive, causing personal and emotional harm to leaders and their organizations?

The challenge is to find that elusive point between inadequate fear, which can lull us into malaise and inaction, and too much fear, which can overwhelm us or our organization, leading to paralysis or toxicity.

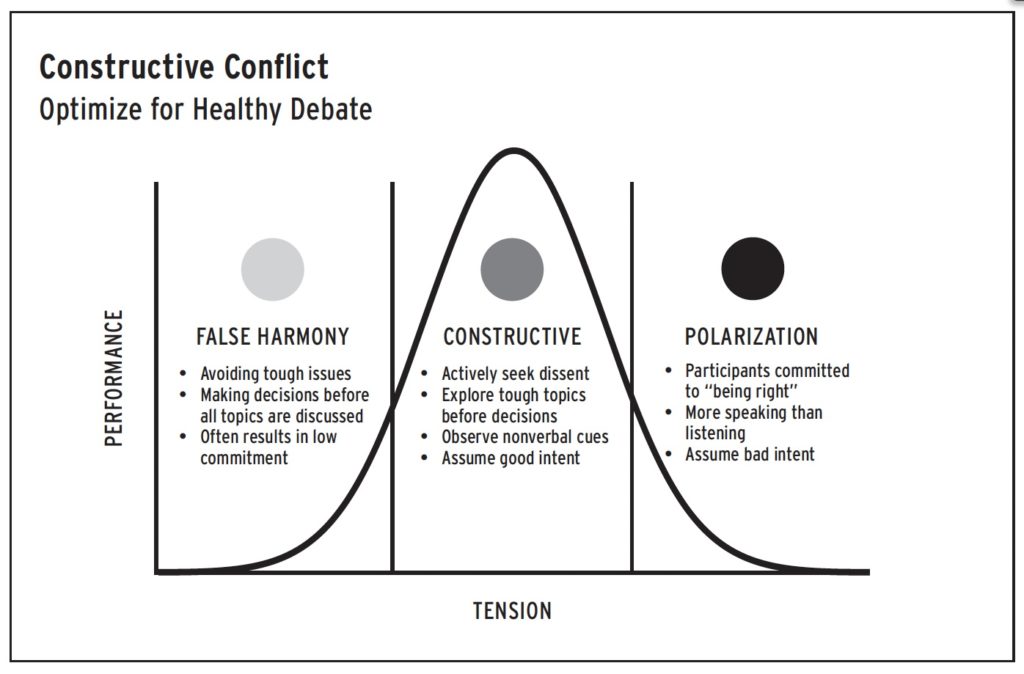

The right amount of fear on teams creates what we call constructive conflict. If there is not enough fear and tension in the system teams fall into what Patrick Lencioni, author of The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, calls “false harmony”: avoiding the tough issues, not having the hard conversations, and making decisions before controversial topics have been discussed.

At the other end of the continuum, teams can find themselves becoming polarized. This is dark territory where team members assume bad intent and are committed to being right because their fears are being triggered.

The ideal is to stay somewhere in the middle, in the zone of constructive conflict, as Steve Jobs so skillfully did with his teams. When teams have constructive conflict, there is enough fear that people are vigilant and take their responsibilities seriously, but not so much that they are hypervigilant and paranoid. There is psychological safety because the fear they experience is a healthy urgency to seize opportunities before the competition does, but not too much fear that creates uncertainty about their standing with the leader or their colleagues or sends them looking for other jobs.

The Leadership Fear Archetypes

In a Harvard Business Review article titled “What CEOs Are Afraid Of,” Roger Jones reports on a study he conducted with 116 CEOs, finding that most executives have deep-seated fears: “While few executives talk about them, deep and private fears can spur defensive behaviors that undermine how they and their colleagues set and execute company strategy.”

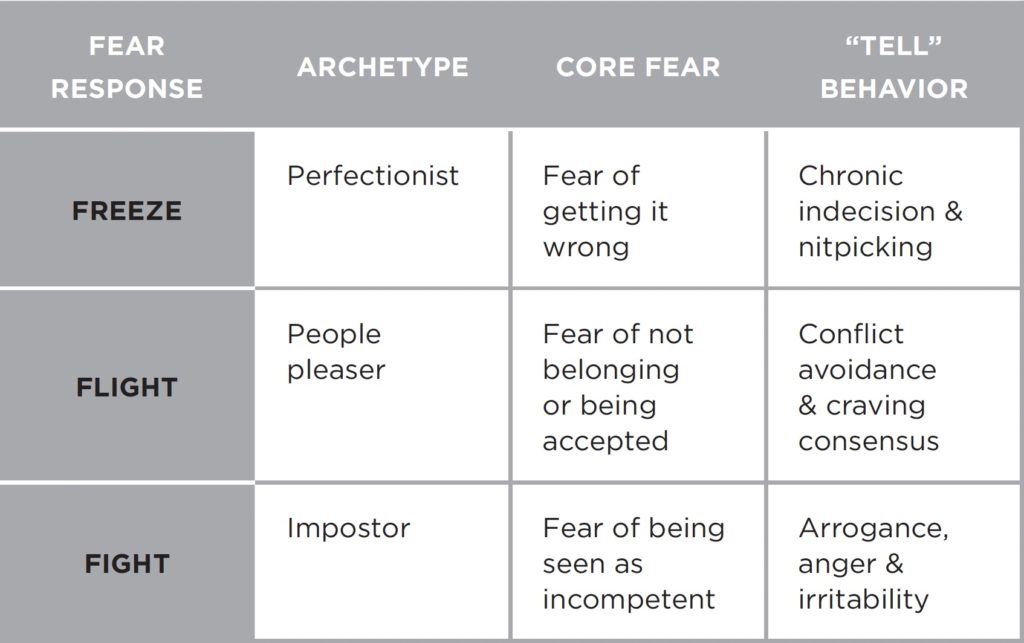

There are three typical fear archetypes that leaders fall into, one for each of the fear responses: fight, flight and freeze. Each archetype has an unexpressed underlying fear, as well as a “tell,” a way of behaving that we can see quite plainly from the outside.

To further understand each of these fear archetypes, let’s meet three CEOs and learn how each of them manifested and managed their fears. As you meet each of these leaders, ask yourself: Which one do you most identify with? Do you identify with all three in different situations or environments? (Since these are less than flattering stories, we have changed certain identifying details of our clients to protect their privacy.)

Chris: The Perfectionist

Chris is the CEO of TeleSafe, a successful software security company. Google recruited Chris right out of school, and after 12 years she was considered an up-and-coming leader who could move easily into an executive leadership role someday. She was known for her thorough approach to products, making sure that things were not shipped until everything was exactly right. She describes herself as “process-oriented,” putting into place the correct procedures and talking to all the right people to be sure every detail is considered and that all relevant parties are brought along.

A few years ago, her former classmate Phil approached Chris, asking her to consider joining forces with him to start a software security company. He’d already secured $1 million in seed capital and had notable early customer traction, but as a CEO he felt in over his head. Chris had always known Phil as an engineer, not a leader, but still she was surprised and humbled when he asked her to join him as a cofounder and become the CEO. He said he thought her extensive leadership experience and process rigor would complement his product and technical strengths.

Fast forward a year later. One of TeleSafe’s investors called us to see if we would consider coaching Chris. He indicated that she was struggling and that board members were raising questions about her effectiveness as a CEO. The investor indicated that Chris was open to coaching and aware that there were issues, but she was not sure how to deal with these challenges.

John started the coaching process by gathering feedback from Chris’s team and members of the board. The feedback that emerged created a picture of a CEO stuck in freeze mode, unable to make key decisions. CEOs in freeze mode are often paralyzed by fear that they might make the wrong decisions.

The comments from Chris’s team were telling:

“There is too much process in the organization.”

“We avoid making key decisions.”

“No one takes responsibility for getting things done.”

“We put off decisions and then fight fires at the end when deadlines are missed.”

“Chris wants to get every detail on our product right, and we never ship on time.”

“We overcomplicate things; why can’t we keep things simple?”

As Chris and John sat in her office overlooking the Embarcadero on a sunny day in San Francisco, she appeared somewhat tense as they began their conversation.

John began by delivering the team’s feedback, which was hard for her to take. Initially she was defensive, claiming that the problem was with her team. She felt that some members weren’t competent, and that she had been slow in moving poor performers out of the organization.

As they discussed some of the feedback that was specific to her, John asked the crucial question: “Chris, what are you afraid of?”

Her answer made it clear that her biggest fear was getting it wrong and putting out a product that would not meet her or the board’s standards. She was fearful that if she didn’t take time to get things right, she would pay for it down the line.

But more than the words that she spoke, John remembers how emotional she became as she explained herself. She choked up as she spoke about how she had built her career on getting things right and not putting out “crap” products. She paused for a moment and in a soft voice described herself as a perfectionist. She argued that she would rather be late getting a product out than not get it right the first time.

Her voice got louder and more defiant as she stressed the need for meetings and thorough reviews to be sure that nothing was missed. As she finished her thoughts, she said, “I’m afraid that if I don’t hold the line on making sure our products are high quality, no one else will.”

After a lot of back-and-forth as to why this was important to her and where these beliefs and feelings came from, Chris and John proceeded to discuss the impact of her behavior on the team and the organization. She admitted that things were not good, and that she needed to make some changes. She was not happy about late launches, last-minute changes, slow decision-making and team members’ counterproductive behaviors.

In her words, she wanted “the team to take more responsibility and step up.” As they ended their coaching session, she observed, “I think I need to change, but I am not sure how or if I can. My need to be thorough and scrutinize everything has always been a strength…it’s one of the reasons I’ve been successful.”

Chris’s behavior clearly fit into the perfectionist archetype. She was so afraid of getting things wrong, she would freeze in indecision and never get anything across the finish line on time. Leaders characterized by this archetype perpetuate a culture of analysis and scrutiny that often paralyzes the team and the organization. Perfectionists rely too much on process, lack timely decision-making, engage in a pattern of firefighting and continually miss critical deadlines.

These leaders fail to take responsibility for decisions and avoid making the tough calls. Perfectionists hide their fear and insecurity behind a veil of nitpicking, scrutiny and criticism.

Andre: The People Pleaser

Andre is the CEO of EduSoft, a successful educational online learning company. EduSoft was founded two years before the Covid outbreak and is now well positioned to support teachers and students in online learning. In short, EduSoft’s tools, resources and software products are hot!

Andre started the company with a few friends after graduate school. Edward first met him after he raised a $40 million investment from a few of the top venture firms in Silicon Valley. In spite of the investment, the lead investor was concerned that Andre, a first-time CEO, was having challenges with the team. He had just hired some new senior executives, and the board was hearing rumblings that things were not going well.

When Edward met with Andre, he experienced him as an outgoing, charismatic, and friendly individual. Andre smiled as he spoke, when he wasn’t focused on listening intently. In general, he presented a very affable persona. This guy is going to be great to work with, Edward thought.

As they began discussing their possible work together, Andre spoke extensively about the new team members and how they were not getting along. According to Andre, “Our biggest problem as a team is that people are not working collaboratively together. Team members demonstrate little respect for their peers.”

After more discussion, Andre and Edward decided that Edward needed to focus on the team and that he should be a “team coach,” with the goal of helping members become more effective. They agreed that Edward should talk to every team member and then observe the team in action.

Edward proceeded to do interviews with each team member and attended one of their weekly executive staff team meetings. His observations confirmed that the team dysfunctions Andre described were real, but that the issues were mostly the result of Andre’s behavior.

It was clear that everyone liked Andre, and that they respected his technical leadership. But it was also clear that Andre’s leadership style, particularly at team meetings, was a major cause of the problem. It was more like an unstructured gathering of friends than a business meeting.

Without a clear agenda or focus, people just brought up topics they wanted to report on or wanted feedback on, and the team debated in circles forever. As a result, there were no clear outcomes, and no one knew what decisions, if any, had been made. As you might imagine, people began to dread Andre’s endless, meandering meetings.

The trouble was that Andre wanted total consensus on key decisions. If there was no agreement, he would table the issue, and on many important topics no decisions were ever made. While Andre listened well and tried to hear all voices, when things got heated, he would back away and avoid the conflict.

As Edward observed the team, he saw visible frustration among the team members that decisions were not being made. After the meeting adjourned, people shuffled out with their heads down and tight looks on their faces. Edward overheard one of the team members whisper to a colleague sarcastically, “Well, another great use of an hour.”

As Edward and Andre walked back to the CEO’s voice, Andre expressed frustration at the team’s inability to collaborate. “I try to give them space to step up and make decisions together, and instead they just debate endlessly.”

Edward suspected that Andre was externalizing the problem and blaming the team for his own lack of decisiveness, but he wanted more data from the team to support his gut feeling. Interviews with the team members supported many of Edward’s suspicions and pointed to additional CEO behaviors that were at the root of the problem.

Nearly every team member mentioned the excessive loyalty that Andre had for some of the early employees he hired, in one way or another:

“These people are no longer effective in their roles, and Andre doesn’t have the backbone to get rid of them.”

“He’s loyal to a fault.”

“He can’t deliver bad news and always avoids difficult conversations.”

“I love him, but he lacks the courage to make the call when he needs to step up.”

“His lack of decisiveness causes us to constantly fight with each other.”

It was clear to Edward that Andre fell into the classic people-pleaser archetype, and that this feedback was going to be difficult for him to take. People pleasers have a baseline fear of rejection that leads them to avoid conflict, giving feedback or sharing bad news. They want to keep everyone happy and drive toward consensus at the cost of progress.

Edward’s feedback was going to hit at the very core of how Andre saw himself. Would he take responsibility and own these problems on behalf of the team? Would the feedback blindside him in a way that would paralyze his leadership? What was Andre afraid of? It was time to find out.

The feedback session started with Andre saying, “I am really looking forward to the feedback. I have a good team, and I know, even though there are issues, everyone has the best of intentions.”

OMG, Edward thought. This is going to be even harder than I thought!

As Edward proceeded to share the feedback, it was apparent that Andre was stunned by all that he was hearing. He literally stopped talking and avoided looking Edward directly in the eyes. After a few minutes, he managed to utter a few responses and asked a question or two, but basically, he was devastated.

About forty-five minutes into the feedback session, Edward could see that Andre was beginning to tear up. In a very low and emotional tone, he started telling Edward how hard this was to hear—that he hadn’t expected the feedback to be so negative. He knew that things were bad and that he could do better, but he had no idea that he was the problem. “Maybe I should just step down,” he muttered. “Seriously. If they don’t think I’m the right person for this, I can go do something else.”

There’s that flight again, Edward thought. The flight fear response often shows up as avoidant behavior: changing the subject away from the hard topic, not addressing issues head-on, or just up and quitting when things get hard.

It was at this point that Edward said, “Andre, why don’t you tell me what you’re really afraid of? What’s the fear that’s coming up for you in relation to this team?”

The CEO then proceeded to talk about his need to be respected by the team. Not to have this respect would be hard for him. He elaborated about his great desire for everyone to get along and to like each other. He talked about the pride he felt in having built a culture where people were happy and worked together in a collaborative way. And after a long silence, he disclosed that he finds conflict uncomfortable and tries to do all he can to get everyone to reach a common ground.

Sensing a breakthrough was at hand, Edward pushed Andre to explore more deeply how and why conflict makes him so uncomfortable. He knew they were tapping into the real stuff. “Andre,” he said, “I can tell that this is hard for you. Tell me a little about what comes up for you when you think about being accepted by a group. Why is it so important to you to keep the peace and make sure people get along? Sounds like that might be a pretty old habit.”

With a big exhale and a glance up to the ceiling, Andre began to open up. He talked about wanting to be popular in school and doing everything he could to be accepted and liked by peers. He talked about his alcoholic father always fighting with his mother, and how he would get caught in the middle between his parents and his siblings. He described his role in the family as the peacekeeper, making sure that everyone got along.

With tears and a lot of emotion, he described how much he hated it when his parents fought. He recalled how his body would tense up, and how he would have this desperate feeling in his stomach. He hated it all so much, he would just run away. He said he ran away from home no less than five times before high school. And when he graduated, he went to a university on the west coast, getting as far from the stress and con0ict of his childhood home in New Jersey as he could.

Listening and observing Andre as he talked, Edward could tell that he was experiencing some anxiety in the moment. “I can tell you’re anxious just talking about these memories,” he said. “Your breath is shallow, and your speech has sped up. Do you ever experience this same anxiety when you are leading the team?”

Andre’s response was telling: he felt this anxiety all the time, especially when people were not getting along and fighting with each other. He was vehement as he expressed how much he hated it when people disrespected each other and couldn’t find common ground. His anxiety was so high in these tense situations, he added, that that he wanted to move as quickly as possible to resolve the con0ict. In Andre’s words, “I quickly employ my peacekeeping skills to bring the group back to finding a workable compromise. This works in the moment, but my team seems worse than it has ever been.”

The people-pleaser archetype is characterized by a habitual flight response to fear. This doesn’t necessarily mean Andre literally flees the room whenever he feels fear or anxiety, but he does his best to flee the moment, doing everything possible to keep everyone happy, change the subject and avoid tension or conflict.

Ironically, efforts to avoid open conflict only cause more of it behind the scenes. Because decisions are not made, team members engage in political maneuvering to advance their positions, often with mounting resentment. This is not an easy archetype to help. With people pleasers, we find the journey to change takes longer and involves deep reflection and healing.

Luis: The Imposter

Luis, a Harvard-educated doctor and entrepreneur, is the founder of HealthX, a health-care company whose mission is to use patient-centered analytics to make the healthcare industry more effective and efficient for both patients and physicians.

John was introduced to Luis through a physician and investor who sits on Luis’s board. The physician was very bullish on the company, which had just completed a Series A funding round of $60 million. HealthX was growing fast, expecting to add fifty new employees in the next few months. The investor was concerned that Luis was continually stressed and having a hard time managing his role as a CEO in this fast growth period. It seemed like the perfect time to introduce Luis to a coach.

Upon first meeting him, John thought Luis seemed open to learning how to better handle the new challenges in his role as a CEO. Luis had never been a CEO before, and he was aware that he had a lot to learn. He wanted the coaching to provide him with some new tools so that he could better lead his company, and talked about how important it was that he be successful. “I don’t want to disappoint anyone!” he said.

Our coaching work with leaders allows them to contact us at any time to discuss an important issue or decision that is causing them stress. We call this the 24/7 option, and Luis began taking advantage of it. A lot.

One afternoon, John and Luis met on short notice at Luis’s request. Luis was noticeably stressed and upset as he talked about trying to balance everything in his life. As the father of newborn twins, he was finding it hard to balance the demands of family life with the pressures of work. His wife wanted him to be at home more. Luis was not sleeping and finding it hard to be calm and in control at work. He even described times where he expe-rienced panic attacks.

In Luis’s 360, the feedback John received from the team painted a picture of a leader who was quick to snap at people and often defensive, causing his employees to shut down in meetings. Team members found conversations with him difficult, as he “had to always be right” and “dismissed the ideas of others.” His colleagues were becoming increasingly frustrated with his “command and control” style of leadership.

During the coaching session where John gave Luis his feedback, it was obvious that Luis was not in a good place. He looked tired and run-down. His eyes were red, and he was noticeably agitated. He started talking nonstop and, frankly, not making a lot of sense.

Seeing a need to change it up, John suggested that they take a walk. Luis agreed, and they stepped outside to take a stroll around San Francisco’s South Park neighborhood, where Luis’s company was headquartered. Luis was in a mood to talk, and walking set the stage for a meaningful coaching conversation.

When John asked Luis what was going on, he said that he wasn’t sure what was happening, but that he was not sleeping. He said he had woken up the night before in a cold sweat, thinking about all the pressure he was feeling. “I had a dream that we had an all-hands meeting, and I had to tell everyone we were winding down the company. It was way too real, John!”

John just listened as Luis talked more about the stress he was under, repeating that he didn’t want to disappoint anyone. As they sauntered along the San Francisco Bay behind the ballpark, there was a long pause. Finally John asked, “Who are you afraid of disappointing, Luis?”

Luis talked about how he was afraid that he would disappoint everyone, especially his parents. He described his upbringing in an immigrant Latino family in Albuquerque, New Mexico. His family was poor, and his parents both worked full-time. His mom held down two jobs—one that started early in the morning and the other a late-night shift.

Luis described his family as one full of love and support. His parents wanted something different for their children. He had two brothers and two sisters, and from an early age, they were all told that they had to get an education. The bar was set very high for all of them.

“My parents wanted all of us to have a better life, and for them education was the number-one priority. There’s a reason why we all studied our butts off and all went to Ivy League schools.” Luis’s energy shifted a layer deeper. Almost in a whisper, he muttered, “There’s a reason why I went to Harvard and became a doctor. I would never want to disappoint them.”

They strolled along in silence for a minute, and Luis continued his story. He began to describe the challenges he’d had since leaving Albuquerque as one of very few “brown kids” (as he put it) at Harvard, the only Latino in his medical school class. He talked about the undermining commentary from his classmates, who would hint that he was only there because of admission diversity goals. “What if they were right, John?!”

And now, as one of a small number of Latino entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley, he had similar worries. Even with a Harvard degree, he felt that he was often not taken seriously. He talked about how hard he had to work to convey the right image, and that he didn’t fit the image of the classic CEO.

In his words: “If you haven’t noticed, I’m not tall and white. I’m small and brown. I still have a slight accent. So I compensate by using bigger words, by being loud, by talking fast all the time. I feel like I’m always selling—always faking it.”

They continued their walk in silence for a few minutes as John let everything he’d just heard sink in. Luis was baring his soul here, and John wanted to give the topic the respect and space it deserved.

After another minute, John stopped walking and stomped his feet together to punctuate the moment. “So, Luis, tell me how these experiences and this belief that you are not taken seriously show up in your leadership. Tell me what are you afraid of?”

Luis let his shoulders fall a little and looked down sheepishly. Then he shrugged and said quite plainly, “My biggest fear is that people will find out that I am not the smart person that they think I am. I sometimes feel like an impostor.”

Bingo!

It was clear that Luis was falling prey to the impostor archetype. Being “found out” is one of the most common fears among all prominent figures, but especially new leaders who have never been CEOs before. A 2019 review of 62 different studies of over 14,000 participants showed that prevalence rates of impostor syndrome where uniformly common among men and women and across a range of age groups, impostor syndrome is particularly prevalent among “ethnic minority groups.”

The Impostor Syndrome has been more commonly spoken about in recent years thanks to the bold and personal revelations of prominent figures like first lady Michelle Obama, actors Tom Hanks and Emma Watson, tennis champion Serena Williams, and former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, among scores of others.

People respond in different ways to feeling like an impostor. Some freeze. Some flee. But in our experience, the impostor archetype among leaders often shows up as fight fear response, like they are trying to hide their fear of incompetency with antagonistic and controlling behavior.

Impostors often put on a thick coat of armor or even an aggressive bullying stance with their teams. “If I can point out the failures in others,” they tell themselves, “they won’t have time to look at my potential failures.” It’s a classic overcompensation move.

The impostor archetype is extremely common among entrepreneurs, especially first-time CEOs, no matter their race, gender or socioeconomic background, but especially so among the BIPOC founders we have worked with. In the words of one founder we’ve coached, “We are all impostors; there is no way I could have had the success I have had without faking it. I just hope I don’t get found out.”

Luis masked his fear of incompetence by acting out the scrappy persona that has worked for him for most of his life. However, this time things were different. Both the physical and psychological effects were taking their toll on him and his company. Luis needed to embrace his fear, and our journey with him was only just beginning.

Making Fear Your Ally

This chapter has introduced you to three different leaders, all of whom struggled with fear. The question “What am I afraid of?” is a hard one to grapple with, and leaders can’t always identify the fears that are impacting them, their teams, and their organi- zations. Of the five Leading with Heart questions, this is often the hardest one to have conversations and create change around. Chris, Andre, and Luis all needed help in identifying the role that their underlying fears played in their style of leadership.

Each experienced and expressed their fears in different ways:

In Chris’s case, her underlying fear and its impact on her leadership were not clear to her. She was aware that the team was not meeting deadlines, but unaware that her perfectionist behaviors, driven by fear of failure, were at the center of the problem.

With Andre and Luis, the fear was beginning to affect them both physically and psychologically, leading them to behave in ways that made them ineffective leaders who were hurting their organizations.

What are the strategies leaders can use to deal with their fears? How can Chris, Andre, and Luis apply these strategies to dealing with their own fears? How can you learn to manage your own fears?

We’ve developed a simple framework that we have found is helpful in coaching leaders to manage their fears.

1. Name Your Fear and Embrace It

In our work, we find that we have more success when leaders are open to embracing their fears. This is not always easy to do, but having a mindset of being open to naming and understanding fear is a good place to start.

Academic research supports the value of facing fears. In her research on leaders and their strategies for dealing with fears, Tonya Jackman Hampton discovered that when they were able to name their fears, leaders were better able to explore and be open to strategies to deal with them. She discovered that while these fears never really go away, they begin to dissipate as leaders identify new ways to cope.

Leaders who view stressful events and fears as challenges to learn from rather than obstacles that could stymie their growth are more likely to improve their performance. Not all clients can embrace their fears right away. With some, it takes time to break down these barriers and move toward change. In other cases, some leaders are unable to face their fears, which can result in the company failing.

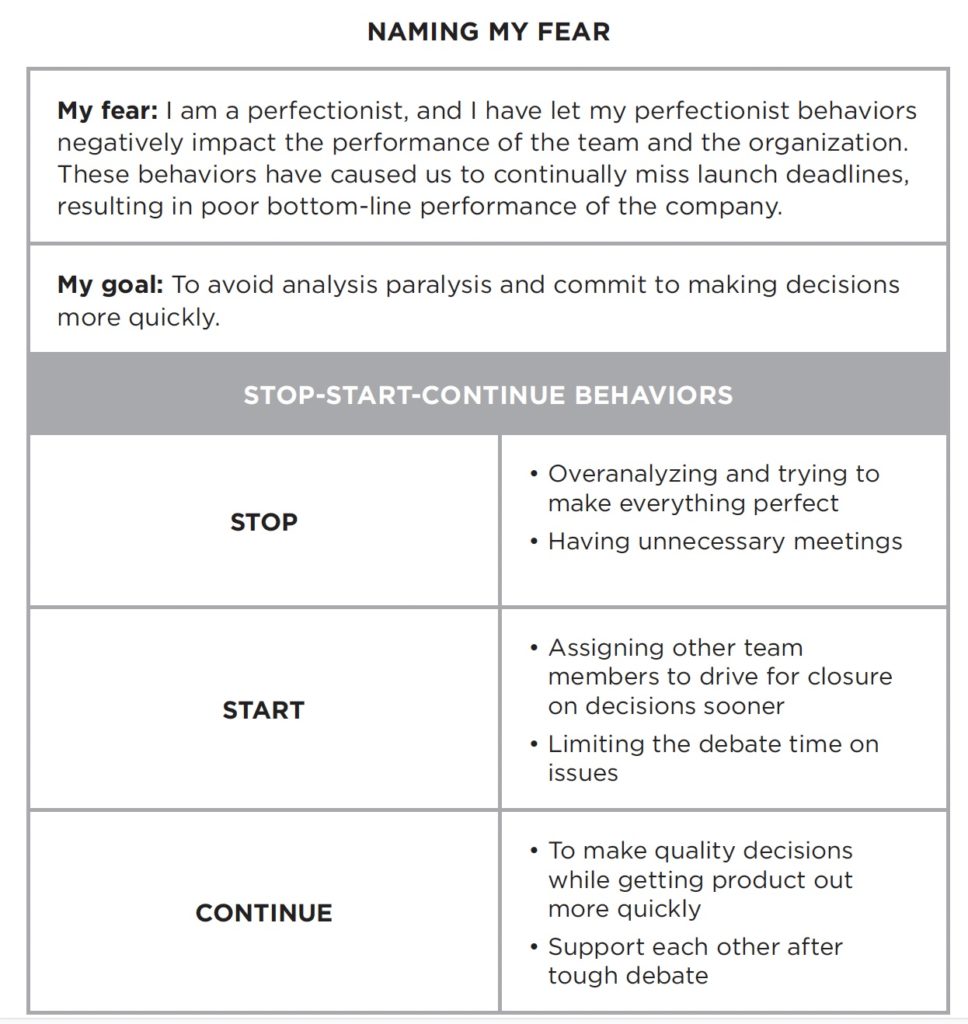

For Chris, our work started making a difference when she was able to name her fear and recognize how her behavior was the primary cause for the poor performance of her team and the organization. By naming her fear, she could then have an open conversation with the team and engage them in helping her develop strategies for change.

This was hard for Chris to embrace at first. She and John worked together to write down and clearly articulate her fear and its impact on the organizational performance. This act of writing is critical in getting leaders to own and embrace their fears.

2. Share Your Fear

Once the fear is named and written down, the next step is to share your fear with members of your team. We often ask leaders to choose a small group of people and ask them to provide feedback on whether this fear impacts the client’s performance. These can be team members or others who work closely with the leader.

We usually coach leaders to use an open-ended process that begins with stating their fear and then encouraging other people to share what fears might be impacting them. Here is the statement that Andre, the CEO identified as a people pleaser, used with his staff:

I have received feedback that our team needs to make decisions more quickly by engaging in more conflict and open debate. Our lack of decisiveness is causing problems among the team, with concerns that key decisions are not getting made. I realize that I am a big part of this problem and that my desire to promote collaboration and consensus can be counter productive. I find conflict difficult and fear that too much conflict will destroy team morale.

This opening statement set the stage for a number of questions that Andre used to gather additional feedback. Questions like:

• Can you help me understand the way you see it?

• What impact has my behavior had on you and the team?

• What behaviors should I stop doing?

• What behaviors should I start doing?

• What behaviors should I continue doing?

Gathering this kind of feedback helps leaders admit and embrace their fears. After collecting concrete feedback on specific behaviors that he should stop, start, and continue doing, Andre was ready to take things a layer deeper.

Working with Edward, Andre and his team were able to have a conversation about their dynamics. Edward established an environment to help everyone feel safe, and that enabled some people to open up and share their stories.

When we take the time to learn about each other’s stories and fears, we are able to understand what’s behind unproductive behaviors. Andre’s vulnerability encouraged others to share. By creating this climate of openness and transparency, people were able to feel comfortable in expressing their opinions. They established a clear set of rules of engagement, which helped define the way that the group made decisions.

3. Make A Plan

Fears run deep and are hard to change. Without a plan of action, nothing will change. The Naming My Fear model is an effective tool to help leaders move from understanding to real action. They start with a plan, but their teams help them expand upon that plan and make sure it is enforced. We find that when leaders are vulnerable about their fears and express a desire to do something about it, people respond in helpful ways.

The agreements identified in the Chris’s plan below served as a “contract” to hold her and her team accountable.

One of the observable outcomes from this process is that team members become more vulnerable themselves, often disclosing some of their own fears. One team member disclosed that he was reluctant to open up for fear that his comments would not add any value. He discussed his fear of not feeling smart enough, compared to the other smart people in the room. Once he identified and named this fear, he could begin to become an active participant in meetings. When leaders take off their armor and embrace their fears, it inspires others to want to reciprocate. With Chris, once she acknowledged her fear and committed to a plan to work on these issues with the team, change began to happen.

4. Tell Your Story

One of the most powerful strategies for making fear your ally is to craft and tell your story to a broader audience. Stories inspire and motivate people, and help leaders connect with their teams. The fears that leaders have are often the same fears being expe- rienced by others. All the leaders discussed in this chapter had compelling stories to tell about their fears.

Luis, for example, had a powerful story to tell—Latino heritage, humble beginnings, always having to work extra hard to prove himself, not wanting to disappoint anyone, especially his parents. His fear of being found out—of being an impostor—or failing was a key driver of his behavior. Luis had to overcome countless barriers on his journey.

Luis had to craft a story that was compelling and authentic, but that also let him display vulnerability while inspiring others. His story needed to show that he was evolving and growing as a leader.

John vividly recalls the coaching session with Luis when they first put the elements of his story together. They began with a brainstorming session in which John asked, “What do you want to say in your story?”

After an hour of back-and-forth dialogue, the following themes emerged from Luis:

- “I want to begin by talking about my family and my humble beginnings.”

- “I didn’t want to disappoint my mother.”

- “What I lacked in size, I made up for in smarts.”

- “I learned to never give up.”

- “I wanted to be taken seriously.”

- “I learned to be resilient.”

- “I was knocked down so many times, but I always got up,”

- “I am learning to embrace my fears and let go more.”

Luis created a 10-minute story from these themes, and committed to share his story at his company’s next all-hands meetings. He asked John to attend the meeting, and according to John it was one of the most memorable moments of his coaching career.

Luis began with his family story, and as he talked about his mother, tears began to well up in his eyes. His authenticity came through as he identified his own fears and how they have impacted his ability to show up and lead with patience and resolve. He concluded by connecting his own story of resilience to the culture of the company. The reaction was overwhelmingly positive, and his story became part of the company lore. From that point on, Luis never missed the chance to tell his story to new employees during employee orientation and onboarding.

What Happened to Chris, Andre, and Luis?

We often get asked about the real impact of our coaching with leaders. Did the coaching make a difference? Did anything change? Was the change sustained?

• Chris: Chris made great strides in her leadership and began to let go of her perfectionistic behavior. Products got out on time. She credits the hiring of a COO and the stop-start-continue activity with her team around her fear as major factors in removing barriers and changing her behavior. Her company went public two years later.

• Andre: Andre made good progress in the earlier stages of the coaching: more debate and con0ict characterized group meet- ings, and new ground rules helped the group make key decisions sooner. This lasted for four or five months, and then Andre began to fall back into his old behaviors. Frustrations began to mount among the team members, and people talked more about leaving the organization. The crowning blow happened when Andre was unable to get rid of a longtime underperforming leader who was a close friend.

A year after the coaching ended, the board brought in a new CEO, and Andre became a member of the board. Andre’s high need for approval and conflict aversion had made it increasingly difficult for him to make decisions and scale the company. While he was not successful in sustaining changes in his behavior, the coaching process did help Andre embrace the transition and support the need for a more decisive and operational leader.

• Luis: Once Luis embraced his fears, he was able to continue to grow and learn. His behavior didn’t change overnight, but as the company grew, he was able to trust his team and empower people more. He learned that he didn’t need to be the smartest person in the room all the time. He considers his storytelling event as the single most important element in helping him take off the armor that was hiding his fears. Luis’s company became wildly successful, and he ended up selling it for a high-nine-figure sum to a Fortune 500 corporation. He has since started a second company, where many of his original employees have joined him.

Fear is a necessary evil. But once you identify your fear, name it, share it and develop a plan, you will be able to tell your story and grow as a leader. When you stop to ask what fear may be motivating someone’s behavior, you can sometimes diffuse it. Fear can be a scary place to go, but we find that leaders who go there are more likely to make more lasting changes.

Excerpted with permission from Leading with Heart: Five Conversations that Unlock Creativity, Purpose, and Results, by John Baird and Edward Sullivan (HarperCollins, June 2022).

[ad_2]

Original Source Link