Surging markets in carbon credits have started to save the planet and save billions of dollars – but they need guardrails from business leaders and regulators to truly succeed.

Worldwide carbon credit trading markets already exceed $270 billion, or more than the GDP of most nations on Earth. They provide incentives for companies to reduce emissions by allowing them to get paid for better behavior. On a wider scale, nations could reap big emissions improvements from conversions to alternative energy, advancing technology, electrification of transportation, development of hydrogen power, and advancing energy efficiency in homes and buildings. The vast Inflation Reduction Act bill is projected to cut carbon emissions by 40 percent by the end of the decade.

Yet lax standards imperil the rise of carbon credit markets: Prices vary wildly from region to region. Compliance remains patchwork. Investors seeking opportunities in these markets can’t always be certain they’re investing in quality.

As much as one-third of climate goals set by the international environmental agreements in Paris and Kyoto will need to be met by carbon offsets that are bought and sold on carbon credit markets. That will require the dreaded R-word – regulation – to assure we’re investing in meaningful change. At the same time, company leaders have a responsibility to better understand the ins and outs of carbon credit trading.

The Wild West

Companies can earn credits in two ways. The first is through the compliance market, where high-emission industries are required by regulators to reduce greenhouse gasses by, say, scrubbing carbon dioxide from a power plant’s exhaust.

The second, known as the voluntary market, comes when companies agree to offset their own emissions by choice, not mandate. This market is used by everyone from airlines to utilities to steel companies. Right now companies are investing in projects like bringing stoves to Africa to replace more polluting wood burners; planting new trees in deforested areas; and paying to keep other environmentally sensitive areas, such as rainforests and peat bogs, off-limits to development. The voluntary market has the potential to grow 100-fold by 2030.

Both the compliance and voluntary markets involve companies buying and selling these credits in their quests for net-zero.

The compliance market already is a $270 billion industry in the U.S. Think of it as more of a collection of markets, divided by region and mission, whose spotty coverage leaves many on the outside looking in. Globally there are 32 compliance markets addressing only 20% of carbon emissions today. Coverage is even more sparse in the U.S. Take the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, for example. It’s America’s first mandatory market, yet it covers only power plant emissions, in just 11 states.

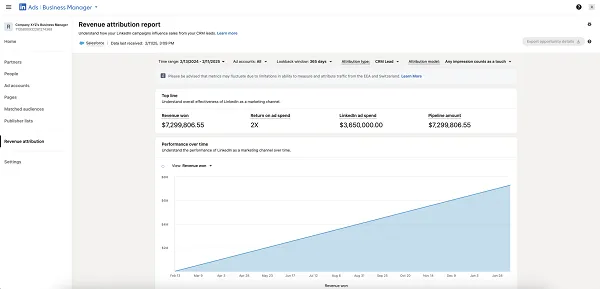

By contrast, the voluntary carbon credit market is much smaller, with about $1 billion of annual trades. To attract institutional investors, this market needs to grow, and trading already has tripled in the past two years.

But obstacles remain. Without standards and enforcement to ensure the true value of a credit, there’s no certitude in how they’re helping the planet. Or if they’re helping at all.

For example, Australia spent $17.5 million on reforestation projects – only to find its woodland area barely increased. The Vatican invested in trees that were never planted. And the absence of regulation has left Greenpeace to call these markets a “scammer’s dream,” rife with bookkeeping tricks.

We’ve Seen This Before

America learned a similar lesson about the perils of a loosely defined credit incentive program in the early 1990s, with the emergence of wind power. At the time, the Department of Energy launched an early version of today’s well-known production tax credit to spur technology investment. But the effort was half-hearted, and wind development stalled for the next decade.

We need to put the carbon markets on a better track. Every day of delay makes it harder to catch up and reach the 2050 net-zero targets most governments and corporations have adopted.

Needed most is reform of the voluntary market, with government agencies, NGOs, and organizations like the World Bank and World Economic Forum encouraging higher standards. They’re in a unique position to serve as independent arbiters, framing the development of these markets in ways that deliver confidence.

It starts with moving toward more uniform pricing and regulated standards. If there’s no common value for a carbon credit, there’s no way for companies to make educated investments. And if we want to show that our climate goals are more than wishful thinking, there’s little logic to spartan tax credits that will leave us decades behind. Especially at a moment when so many companies are eager to invest if the conditions are right.

Be it through wind development 30 years ago, or the carbon markets of today, we’ve already seen how ad hoc affairs play out. If we’re truly serious about climate change, leaders both public and private will insist on reform. The very future of the planet is at stake.