CEOs have become pretty set in their perceptions of the business climate in many states, especially those on the east and west coasts. But there’s still lots of movement in what company chiefs see as the business-friendliness of many other states, and CEOs’ conclusions are being driven by new factors ranging from the rise of AI to relative housing costs.

Those are some of the main takeaways from our 2024 Chief Executive Best & Worst States for Business survey of more than 600 American CEOs, with representation from every state, to gain their perspectives on state business climates and how they have changed — or not.

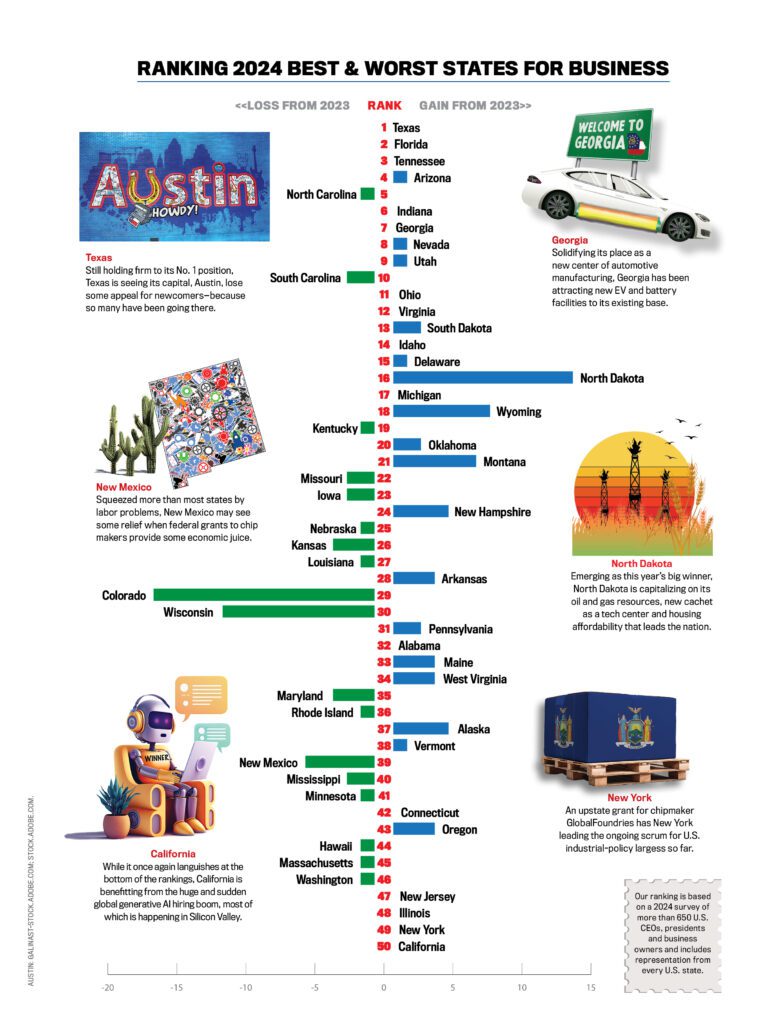

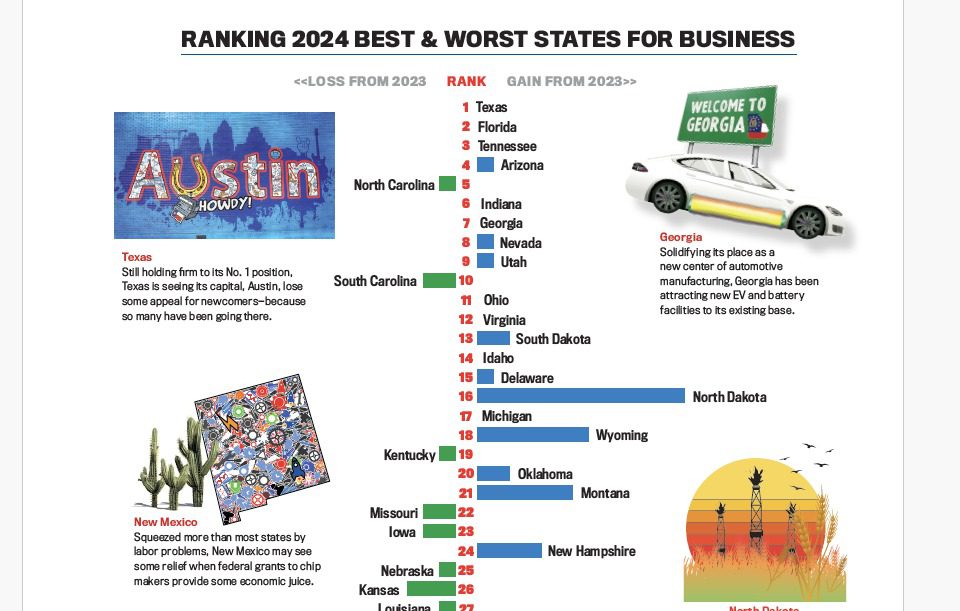

Texas once again placed No. 1 and Florida once again No. 2 in the Chief Executive survey of Best and Worst States for Business for 2024, the pattern for nearly the entire history of the annual survey that began in 2001. Tennessee solidified its recent status as No. 3 in the 2024 results, while perennial top-of-the-listers Arizona, North Carolina, Indiana, Georgia, Nevada, Utah and South Carolina rounded out the top 10.

At the same time, the rump of the rankings was pretty much unchanged as well. California remained at No. 50, preceded by New York at No. 49, Illinois at No. 48, and New Jersey at No 47. There was a bit of movement just above the rankings from those four, but all of the bottom 10 were the same coastal states as last year.

In between the top 10 and bottom 10, however, came some major changes in status, as often is the case. North Dakota advanced 13 places, to No. 16. But New Mexico sank five spots, to No. 39, while Wisconsin plunged by 11 places to No. 30 from No. 19, and Colorado suffered the worst loss, by 16 spaces to No. 29.

These results are especially significant this year because CEOs are demonstrating greater restlessness. Fully 49% of them in the Chief Executive survey said they were “more open to examining new locations for your business.” Also, 44% of CEOs said they were “considering opening or expanding new operations or facilities in a new state,” while 35% were considering shifting operations to a new state.

One reason for the foment is the drivers of economic development in this country have undergone significant change in the last year alone. The post-pandemic swoon in commercial real estate has only begun as leases come due. Construction of mammoth EV, battery and chip-making plants has slowed. And generative AI has dropped like a bomb on the economy, setting off a chase among both corporations and locales for new bounty in the form of data-center construction.

Even state tax policy, always an important indicator of whether a state really wants to welcome business, seems to be taking more of a back seat. The winners in the Best and Worst States for Business tend to be low-tax locales or tax-cutting states, for sure. But partly because so many states have been flush from Covid-era federal funds, greater fiscal responsibility has become table stakes in the economic-development game: 17 states are planning to cut both business and income taxes this year, according to the Tax Foundation, while six are cutting corporate income-tax rates and 14 states are trimming individual income- tax rates.

“Taxes have been cut in so many states that it’s now taken for granted, but many corporate decision-makers have expectations that states will continue to find ways to cut taxes,” says Larry Gigerich, outgoing chair of the U.S. Site Selectors Guild and managing director of Ginovus economic-development consultants. “Probably 30 to 35 states have become really competitive from a tax and business-climate standpoint and now are faced with the decision to keep cutting taxes or say, we need to invest more in infrastructure, talent and quality of life.”

For these and other reasons, new types of competitive advantages are coming to the fore in CEOs’ site-making decisions, including housing affordability and general quality of life. In the midst of a continued labor shortage with the U.S. economy’s soft landing this year, innovations in training and education of workers have become even more important. And as doubts fester about the reliability of the American electric grid, chiefs in power-hungry nascent industries are looking more closely at energy availability.

North Dakota is an example of a big winner in the 2024 Chief Executive rankings that is taking advantage of some of the current drivers behind site decisions. The state topped a recent ranking of housing affordability by Broker.com, which indexed home prices with income; heartland states also comprised the rest of the top 10. Other advantages: 60% of North Dakota residents pay no income tax, on its way statutorily to 100%. The state has invested heavily in its own transportation infrastructure rather than wait for federal largess. And even its status as a top natural-gas producer has gone “green” as North Dakota finances a new form of carbon-negative oil well.

“Three years ago, we had $2 billion worth of projects looking to locate in North Dakota, and today it’s $64 billion,” says Josh Teigen, the state’s economic-development chief. “We prioritize innovation over regulation.”

But New Mexico is an example of a state that is being punished by CEOs this year.

Particularly hurting New Mexico — with 2.1 million people, it ranks only 46th in population density — is a paucity of workers. “The state’s labor force holds the state back from economic development and expansion,” said a late-2023 report by New Mexico’s Legislative Finance Committee. New Mexico needs about 116,000 more workers than it currently has employed just to reach the national average of workforce participation.

Mark Roper, New Mexico’s acting head of economic development, contends the issue is overblown and that companies can find the workers they need. “When Intel did its latest expansion in the Rio Rancho area and was hiring 100 positions,” he says, “we had a job fair that drew 1,000 people to apply, and the company was able to fill those positions within 48 hours.”

In any event, in this environment, even small changes by states can help tip the scales in their favor. For instance, Pennsylvania recently adopted streamlining of permits for new construction, created a single office to handle them, and instituted a mandatory refund of application fees if the state fails to issue a permit on time. CEOs have taken notice, and the state rose by two spots in the new Chief Executive survey, to No. 31.

“Most categories of regulation are well-intended, but there are so many policy areas where some very blue-leaning governments could easily adjust regulations, such as in some environmental areas, to maybe strike a slightly different balance,” says Cullum Clark, director of the Bush Institute-SMU Economic Growth Initiative at Southern Methodist University. “But most aren’t doing that.”