To those familiar with French New Wave cinema, the name Éric Rohmer needs no introduction. Yet, it could also be said that Rohmer, in spite of his prestigious standing within cinephile circles, is admittedly less of a household name than, say, Jean-Luc Godard or Francois Truffaut. He occupies a stratum that includes similarly revered, perhaps less universally known names like Agnes Varda, Claude Chabrol, and Jean-Pierre Melville: artists whose accomplishments have only grown richer with time. If Godard’s experimental, politically incendiary work took him to the furthest reaches of what cinema as a medium would allow while Truffaut devoted most of his career to examining the pitfalls of youth and young manhood, then Rohmer too undeniably had a “thing” that was his and his alone. Rohmer’s specialty was crafting literary-feeling works of cinematic humanism, almost always centered around bourgeoise intellectuals who were frequently teetering on the precipice of some kind of moral crisis.

Rohmer’s characters are always saying the quiet part out loud, constantly over-analyzing other people’s behavior in a manner that generally comes naturally only to academics and actors in French movies. Their business involves traversing the gulf between how they feel and how they’re carrying themselves in the real world. Rohmer’s film work spans the early 1960s all the way into the 2000s, and in spite of being known for making what most would now know as “a Éric Rohmer movie,” the man never received appropriate credit for how experimental he ultimately allowed himself to get (see: the droll, heightened Arthurian fantasy of Perceval, the unassuming anthology effort, Rendezvous In Paris, and the uncommonly candid voiceover in Chloe In The Afternoon, to name but a few).

The truth is that Rohmer is every bit as influential as Godard and Truffaut – perhaps even more so – particularly when one considers that writer/directors like Noah Baumbach, Alex Ross Perry, Hong Sang-Soo, and Mia Hansen-Løve all owe a considerable creative debt to his work (Baumbach took his worship of Rohmer a step further than most, titling his 2007 psychodrama Margot at the Wedding in the style of something like Pauline at the Beach). So, without further ado, here are five of our favorite classic films from this iconic director to get your Rohmer binge started. Enjoy!

The Aviators’ Wife

The first entry in Rohmer’s Comedies & Proverbs series that also includes gems like The Green Ray and Boyfriends and Girlfriends, The Aviator’s Wife is a blissfully meandering study of jealousy and wayward discovery that plays out as a kind of low-stakes detective story told in reverse. Our hero, François (Phillipe Marlaud), is a typical Rohmer protagonist: privileged, intelligent, and insecure, with far too much time on his hands. One day, François sees the girl he loves hanging out with her ex, a dashing airline pilot. Consumed with the notion that his partner is cheating on him, François starts to follow the pair around, only to stumble into more surreptitious, unexpected discoveries along the way. While the notion of a possessive man following a woman around based on little more than a hunch could play out disastrously in the wrong hands, Rohmer, as always, keeps things light and Martini-dry, never once forgetting that the joke is on François’ pomposity and unchecked sense of male entitlement.

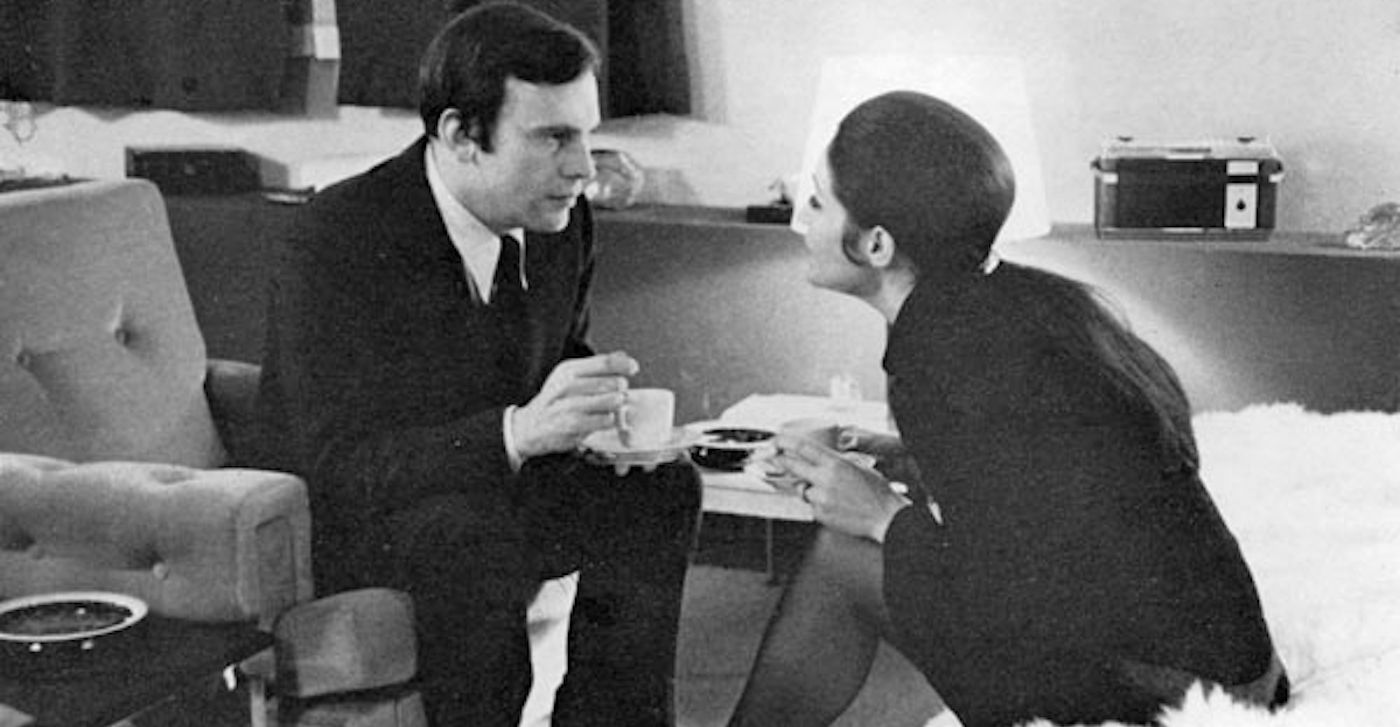

My Night at Maud’s

My Night Aa Maud’s is a wistful reminiscence, shot in grainy, gorgeous B&W, that marks the first feature-length effort in the Moral Tales series. The film is a peerless study of asceticism and desire, and how our basic need for human connection – sexual, romantic, or otherwise – is often at odds with our selfish desire for solitude. French cinema legend Jean-Louis Trintignant (Amour, The Conformist) plays Jean-Louis, a dour and overly righteous man who has his principles challenged when he finds himself attracted to a forthright divorcee named Maud (a magnificent Françoise Fabian) over the course of one night where seemingly everything and nothing happens all at once. My Night at Maud’s, if nothing else, sees Rohmer evolving from the bittersweet, somewhat jagged ruminations that define early short-form work like The Bakery Girl of Monceau and Suzanne’s Career (both part of the Moral Tales series) to the now fully-formed aesthetic that we can readily identify as the Rohmer style.

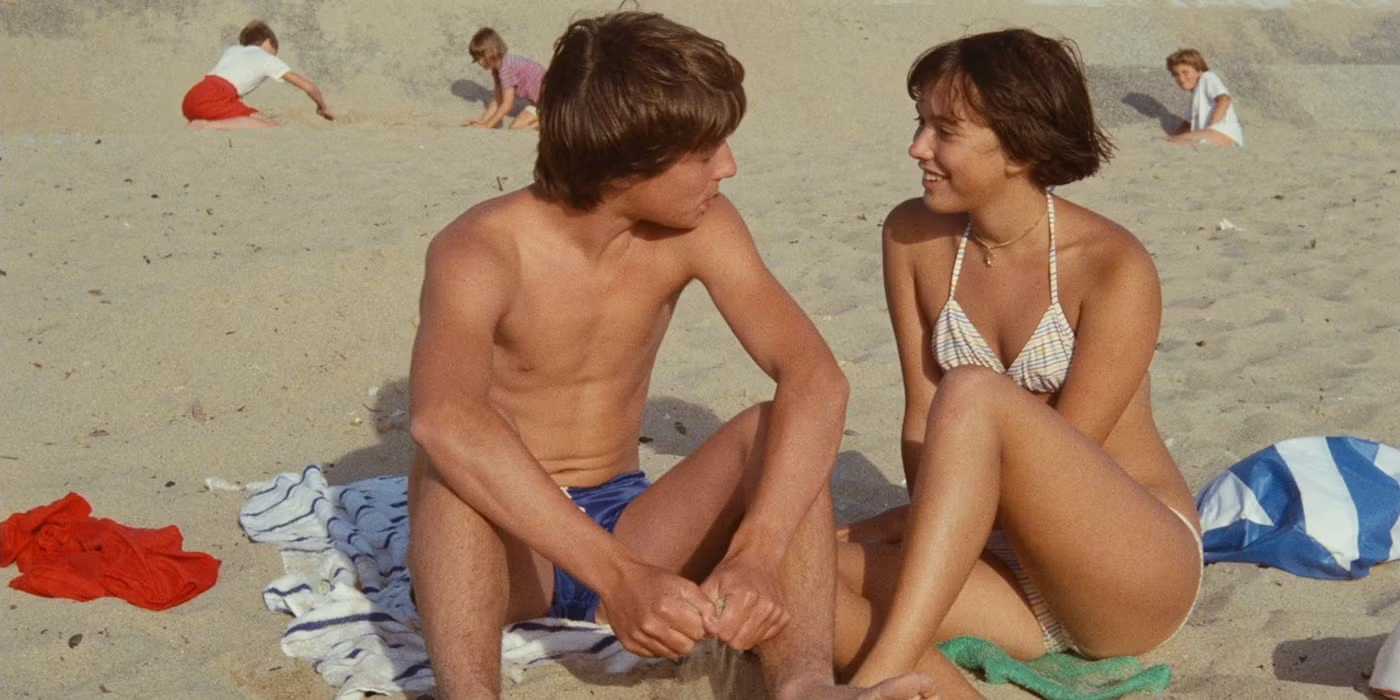

Pauline at the Beach

The third and most evocative entry in the Comedies and Proverbs series, Pauline at the Beach is a film that evokes the sticky sensation of a humid, aimless summer’s day: it’s a work full of exposed flesh, barely suppressed longing, and an overriding sense of ennui. Few filmmakers are as adroit at portraying downtime and the act of wasting the hours away, and Pauline at the Beach ends up being quietly riveting even when it feels like nothing is really happening. The story of two girls, Pauline (Amanda Langlet) and Marion (Arielle Dombasle), who are vacationing at a beachside family home on the coast of France, Pauline, like any great Rohmer film, is a study of people who are hindered by the compulsion to think before they act. It is a rueful comedy of errors filled with unrequited desires and things left unsaid. In practice, though, Pauline feels as pleasant as a breeze blowing through your hair on a cool August afternoon.

La Collectioneusse

Subtitled “The Collector” for its female lead who is said to be a “collector” of men, La Collectioneusse is both one of the most visually arresting pictures Rohmer ever directed, and also one of the most stinging condemnations of masculinity in the entirety of the French Nouvelle Vague. The film concerns two rich, bored friends who are determined to spend their summer doing as little as possible beyond swimming, reading, and engaging in the odd philosophical debate. Their fragile bubble of co-dependent, masturbatory laziness bursts upon the arrival of Haydée (Haydée Politoff), a young woman whose carefree ways throw the men’s idle habits into disarray. There is a tendency in some French New Wave pictures to either romanticize or gloss over gross male behavior, so it’s refreshing to see an artist as normally even-tempered as Rohmer eviscerate the male ego to the degree that he does here. Filmed with largely available natural light by cinematographic legend and regular Rohmer collaborator Néstor Almendros (Days of Heaven), La Collectioneusse is a criminally overlooked jewel in this filmmaker’s crown.

Claire’s Knee

If you had to show a friend one Éric Rohmer film that somehow contains everything that makes him a singular, one-of-a-kind artist, you would probably show them Claire’s Knee, which is something close to a perfect film. All the trademarks of an Éric Rohmer movie are here: the lush, postcard-perfect locales, the languid, wandering conversations, the suggestion of intimacy, and the ruthless pull of temptation. Describing what the film is about is almost irrelevant: our hero meets an old acquaintance and eventually finds himself strangely pulled towards an enigmatic woman named Claire. The literal significance of the title alludes to our protagonist’s yearning to touch something he knows he should not touch – arguably, the most pronounced authorial motif in all of Rohmer’s filmography. While it’s true that every film lover’s favorite Rohmer movie varies from person to person, we would venture to guess that most would include Claire’s Knee in their top five when it comes to this particular director.

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)