[ad_1]

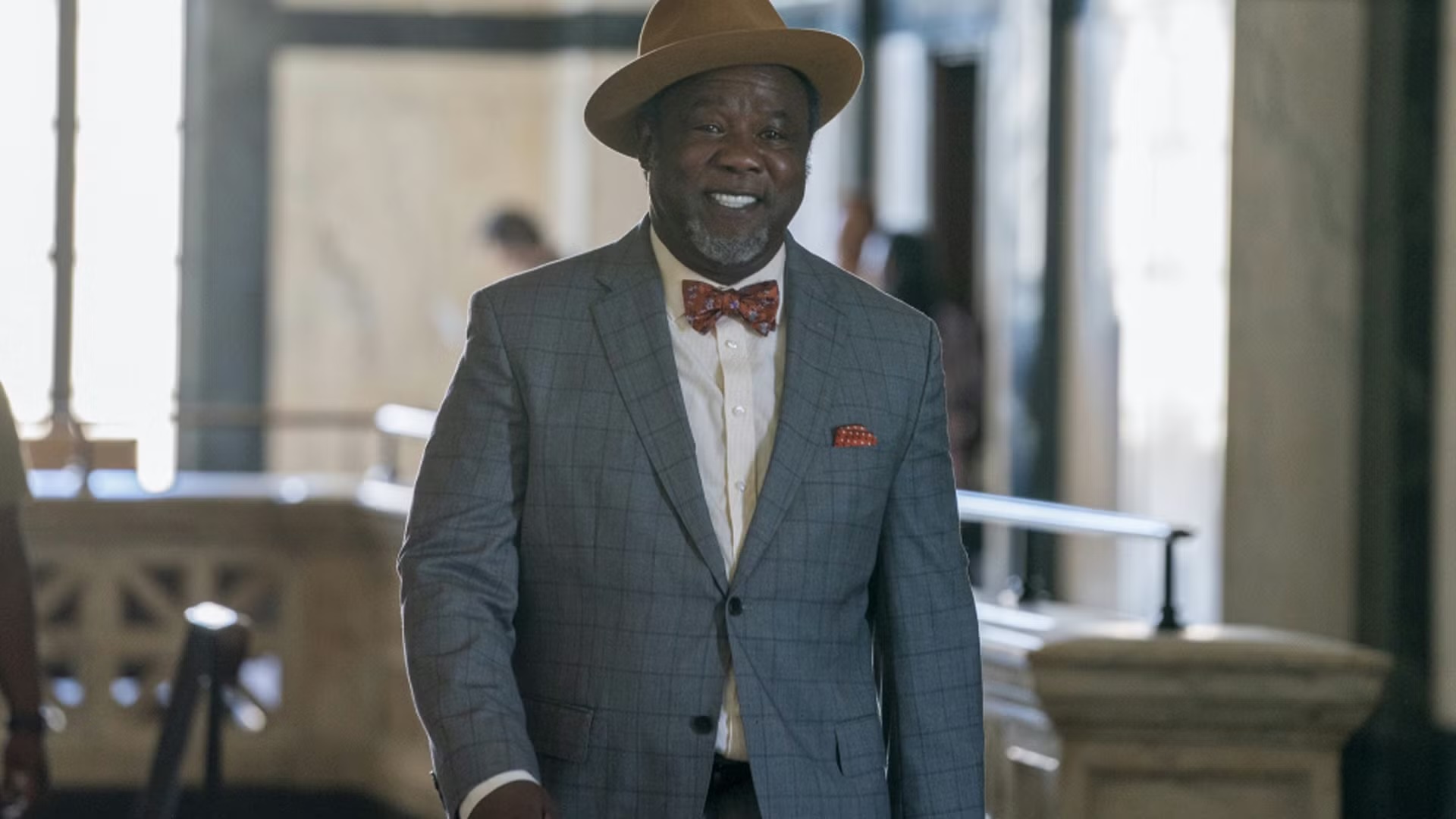

It’s 1966, and Bernadette and Melvin are in Accra, Ghana, far from their American home. They’re not there for pleasure—the couple are on the run after Melvin, held at gunpoint by a racist White man outside an Alabama restaurant, grabbed the weapon from the bigot and shot him. “I killed a white man in Alabama, that’s the electric chair,” Melvin tells his fiancee. “They gon’ say you my accomplice.” Melvin decides only one person can help them: his old college friend Kwame Nkrumah, who happens to be the president of Ghana. When Bernadette and Melvin, pretending to be a pastor and his wife, meet Kwesi Kwayson, a highlife musician, and find out he’s scheduled to play a show for Nkrumah, they insist on tagging along, hoping the president can offer them protection. But Bernadette develops oddly instant feelings for Kwesi, writing in her diary, “I just met a man and it felt like an out of body experience. As if I had known him my whole life.” Meanwhile, an FBI agent named Hughes travels to Ghana, hoping to apprehend the couple he just missed arresting in the States. Bazawule renders the cat-and-mice aspect of the novel well; a filmmaker, he’s gifted at narrative pacing. Unfortunately, that’s the only part of the book that works. His adjective-heavy writing is stilted and awkward, and he makes frequent use of clichéd phrases like “The day began like any other” and overly expository formulations like “At that moment, he concocted a plan that would have far-reaching consequences.” In several passages, he takes jarring detours into magical realism that feel out of place, throwing the reader out of the narrative, and he indulges heavily in melodrama, making the novel resemble a bizarre soap opera. The result is a book that feels like a screenplay that’s been wrestled, awkwardly, into prose. This doesn’t seem like a finished novel so much as an underedited first draft of one.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link