Every Jurassic Park dinosaur is made from previous dinosaurs. The creators of the original park found fossilized mosquitos full of dinosaur blood, extracted it, and then used the DNA it contained to bring extinct animals back from the dead. By the time the franchise got to Jurassic World, one of Jurassic Park’s former geneticists was splicing various genes together to create super dinosaurs like the “Indominus Rex.”

The Jurassic Park sequels have been made the exact same way; the DNA from the old movies is used to create new films. Jurassic World embraced the vision of a dino theme park from the original film on a massive scale. Its sequel, Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, reimagines Jurassic Park III, with survivors of a previous dinosaur catastrophe lured back to the island under false pretenses for a rescue mission with hidden motives. But the most influential Jurassic Park on the Jurassic World franchise is one that was never made.

That would be Jurassic Park IV, which spent more than a decade in various stages of development after Jurassic Park III. By 2002, a year after the release of JP III, Steven Spielberg was already bragging in interviews about the “wonderful story” idea that he had to work with on IV. It was allegedly so good, in fact, that he boasted it was the best idea for a Jurassic Park “since the very first movie” and that he wished he had thought of it in time to make it the premise of Jurassic Park III.

Spielberg was cagey about the details, but a few years later a Jurassic Park IV screenplay surfaced online, credited to John Sayles (and based on ideas by Spielberg and an earlier draft by The Departed’s William Monahan). To put it mildly, the script is nuts. It features soldiers of fortune, drug dealers, and Swiss super-villains in addition to all the typical dinosaur action. What’s really nuts, though, is how many of the concepts from this unfilmed screenplay found their way into the Jurassic World series.

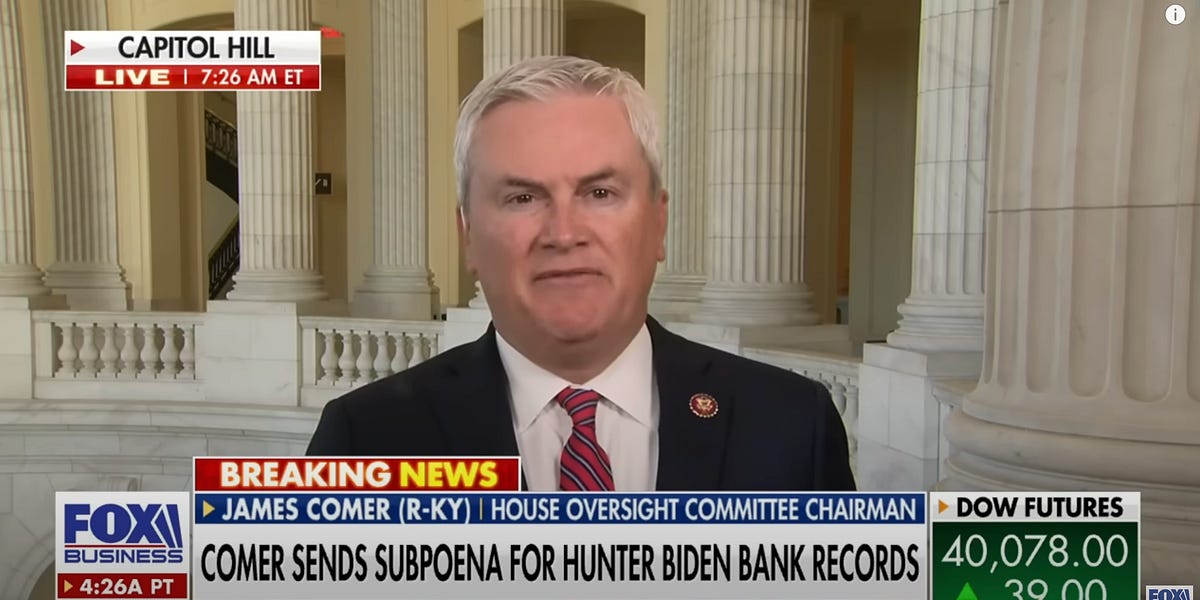

Jurassic World 2 Fallen Kingdom

Its hero is an unemployed mercenary named Nick Harris. Jurassic Park founder John Hammond recruits him for a dangerous mission to Isla Nublar and the ruins of the original park. Hammond needs Harris to find the shaving cream can full of dinosaur embryos stolen in the first film by Wayne Knight’s Dennis Nedry, who died during his escape from the island. Another company has bought Isla Nublar, and Hammond is terrified they will find the embryos and use them for evil purposes.

It was clearly established in Jurassic Park that Nedry’s Barbasol can only had enough coolant in it to preserve the embryos for 36 hours, but whatever; Harris accepts the assignment and travels to Costa Rica. He manages to find the can, and evade the island’s dinosaurs, but he’s attacked by soldiers working for the park’s new owners. He stashes the embryos, then gets knocked out and captured. And that’s when things get really weird.

Nick wakes up in a medieval castle in the Swiss Alps of all places, where he’s held hostage by Baron Herman Von Drax, a name I swear I did not make up. Von Drax wants those darn embryos, and while he negotiates with Harris, he shows him his prized possessions: A team of highly-trained, genetically-engineered raptors that can be controlled via hormone injections. Von Drax makes Harris an offer he can’t refuse: Use his unique warrior skills to finish training these raptors for combat, and maybe he won’t feed him to his pet dinos.

Then Nick trains the raptors to become raptor soldiers. Raptoldiers, if you will.

As part of their training, Nick leads the dinosaurs on several rescue operations which Sayles’ script goes to hilarious lengths to prove could only be handled by a team of highly trained raptors. For example, Von Drax’s henchman Joyce tell Nick about a little girl who’s been kidnapped. Nick suggests they put together a team of expert special forces dudes to find her. No way, says Joyce; they’ll never find her in time! Okay, why not have just one dinosaur sniff out the kid and then send in the SEALs? Won’t work, Joyce insists! They keep the girl in the center of the room, so a firefight would be too dangerous. No, this looks like a job for… raptoldiers!

At the end of the film, the raptors turn on their masters (of course), Nick saves the hidden embryos he retrieved from Jurassic Park, and returns them to Hammond. Rejuvenated by his time training de-extinct death beasts from 65 million years ago to triangulate enemy positions, he lives happily ever after — or at least until the growing dinosaur population on Earth reaches the point that it destroys human civilization.

Sayles’ script (which you can still find and read in its entirety online, because the internet is an even better preservative than ancient amber) opens in fairly standard Jurassic Park fashion (pterodons attack a Little League game) but after Harris’ introductory jaunt to Central America, it takes a sharp left turn into Crazy Town. The climactic action scene involves a raid on a drug kingpin’s compound, culminating in a parody of the end of Scarface — plus freaking dinosaurs.

(Whoops, I should have warned you about spoilers for an unmade screenplay for Jurassic Park IV. My bad.)

Every scene involving Baron Von Drax (apparently Sayles’ attempt to one-up the ludicrous Sir Hugo Drax from Ian Fleming’s Moonraker) is insane. In one, he offers a toast to his “victorious reptiles!” For the big action finale, he sends the raptors parachuting out of airplanes. Yes, dinosaurs wearing parachutes is a thing that existed in a real script for Jurassic Park IV.

Von Drax convinces Nick to become his new raptor trainer, and then Nick gives all the raptors classical Greek and Roman names; the leader is Spartacus, which is maybe not the best name to give an enslaved and hyper-intelligent claw monster if you don’t want it to rise up and turn on his masters. Sayles’ screenplay mutated further from there; there’s supposedly a draft that involves dinosaur-human hybrids. (I haven’t read it, but concept art that’s from this era of Jurassic Park IV is floating around on Instagram.)

Eventually Spielberg abandoned the Sayles and Monahan scripts, possibly because there is no way on Earth audiences would have accepted a Jurassic Park about dinosaurs with laser cannons for arms. Time passed and a new round of development began, which ultimately resulted in Colin Trevorrow’s Jurassic World, and now J.A. Bayona’s Fallen Kingdom. For the first Jurassic World, Trevorrow and his team rewrote another screenplay by Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver driven by three directives from Spielberg’s: “The park is open, there is a raptor trainer, and a dinosaur breaks free and threatens the park.”

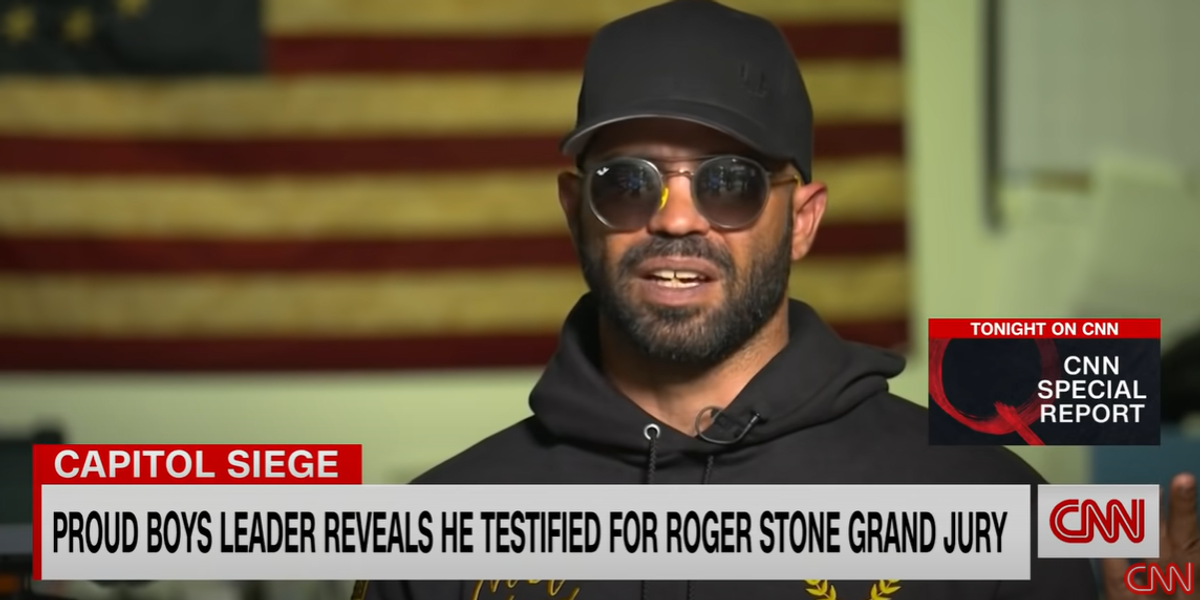

Although the raptor trainer in the Jurassic World films has a different name (Owen Grady instead of Nick Harris) he bears a striking resemblance to the character in Jurassic Park IV. He’s both an animal trainer and a former soldier, and while he has serious reservations about using the raptors for military purposes, he also goes along with the plan (and seems to get off on the thrill of the hunt). Nick and Owen have the same combination of skills; fearless fighter and intuitive animal behaviorist. And both guys also like to name their trained raptors.

Jurassic World Chris Pratt

There are other connections between Jurassic Park IV and Jurassic World. Both feature genetically engineered dinosaurs; both feature dinosaurs who have the ability to camouflage themselves based on their surroundings. Fallen Kingdom shares even more similarities with Sayles’ Jurassic Park IV. For one thing, their structures are nearly identical; a first half set in the overgrown ruins of Jurassic Park and a second half trapped in a wealthy eccentric’s gigantic and garishly appointed mansion. There are even scenes in both where wealthy buyers come to examine the dinosaurs and bid on their services.

These could all be coincidences, but in a 2015 interview with ScreenCrush, Trevorrow admitted he had read the Sayles Jurassic Park IV script during the development of Jurassic World. “I was so curious,” he told us, adding “I liked it in a lot of ways. I knew what was going on. What was going on was bananas, but that’s not a bad thing! My movie is bananas. There’s a lot in there to like. It’s nuts in a lot of the right ways.”

Even if Trevorrow and his co-writer Derek Connolly didn’t consciously lift elements from Jurassic Park IV, its influence can be felt up and down their franchise. Still, as wild as the Jurassic World franchise got, it never got as strange as this unmade Jurassic Park IV.

The Best Sci-Fi Movie Posters Ever