The Big Picture

-

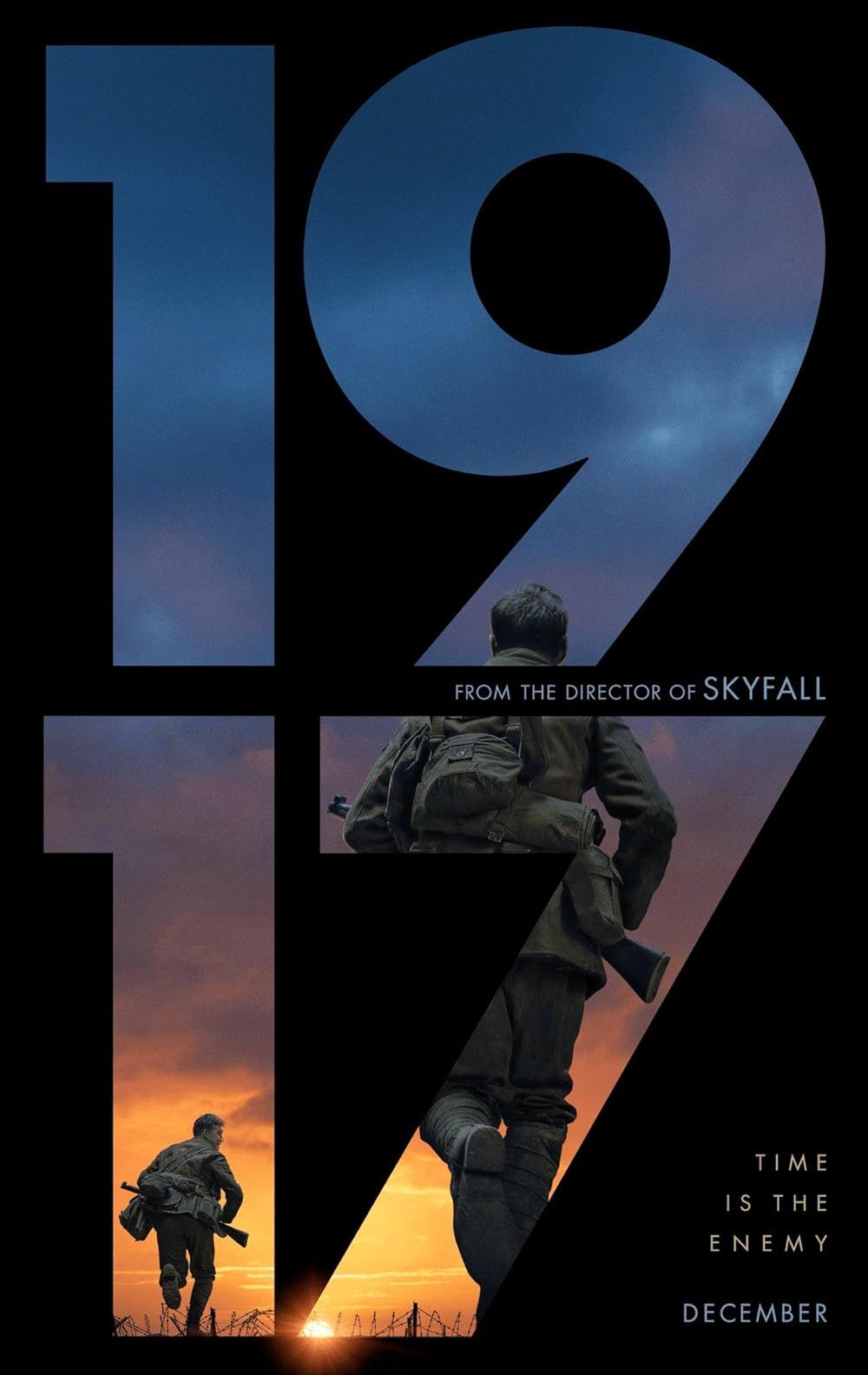

1917

and

Birdman

use editing tricks to create the illusion of one continuous shot, adding to the immersive experience. -

Boiling Point

and

Russian Ark

are real one-shot films, showcasing the meticulous planning and effort required for authenticity. - One-shot films, whether real or fabricated, require immense precision and consistency both in planning and execution to bring the story to life on screen.

Since its early days, film has been a medium of gimmicks. Even elements we take for granted, like sound and color, started as a way to make the audience exclaim in amazement and wonder just how the filmmakers managed to pull it off. It’s an illusion, movie magic, and it was a surefire way to put butts in seats. Visionaries like William Castle made a whole career from various audience-grabbing tricks he would use in cinemas. Decades pass, and audiences evolve with each year, but filmmaking gimmicks never truly go away. We’ve just seen smarter, subtler, and more innovative ways of presenting them. 3D is a gimmick that has become an industry standard, but other films that have centered on their gimmicks have been celebrated and acclaimed. Boyhood‘s 12-year filming process, Tangerine being shot entirely on iPhones, and The Artist being a modern silent film are celebrated as contemporary pieces of art and movie-long gimmicks. One that rarely fails to intrigue an audience, whether it’s shown in part or whole, is the long take.

There are a lot of long takes in film history that people consider the best, whether it be because of a captivating performance like in Les Misérables or Call Me By Your Name, or it being an iconic visual spectacle, like in Goodfellas or The Shining. A scene of uncut action or emotion has a way of keeping an audience’s fleeting attention. But what if, instead of mere minutes, the long take lasted a film’s whole duration? This is where a one-shot movie, like Sam Mendes‘ 1917, comes in, a film that is, or appears to be, done in one, long, continuous take. The presence of cuts in a film is so commonplace that it’s taken for granted, so its absence is felt. As a result, the film is given an element of immersion and depth, as if the director is taking your hand and pulling you along for the ride. The long take is difficult to pull off, and relatively rarely used in cinema history because of this. When a one-shot film is done well, however, it pays off significantly, with audiences following their curiosity right to the box office.

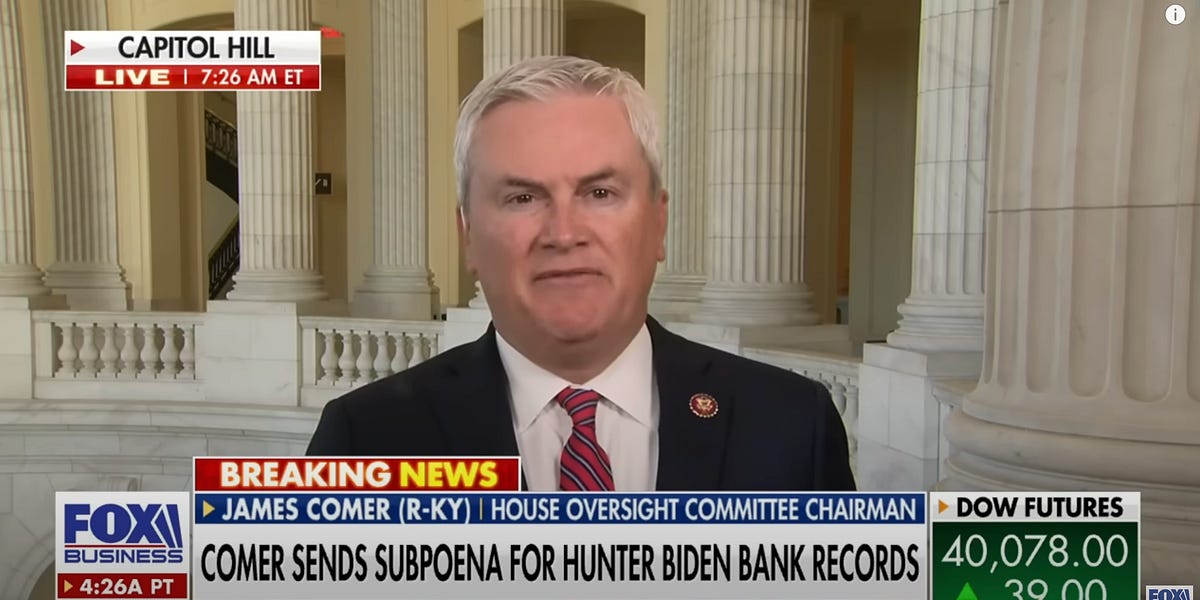

‘1917’ and ‘Birdman’ Weren’t Filmed in One Shot, but Used Skillful Editing

Two one-shot films have gotten the most mainstream attention in the 21st century. 1917 is Sam Mendes’ heart-pumping interpretation of a real World War I battle, with two young soldiers desperately racing against the clock to save their fellow soldiers, and Birdman, aka BİRDMAN or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), is Alejandro González Iñárritu‘s Best Picture-winning dark comedy about a washed-up actor’s desperate comeback. In 1917, you feel as if you’re running alongside Will Schofield (George MacKay) and Tom Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman), as you witness just how fast the violence and death of the First World War can come at you, and how precious those rare minutes of rest can be. Similarly, in Birdman, Iñárritu said in an interview with Variety that we live our lives with no editing, and he found that the best way for the audience to remain in the scattered mind of Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) was through the one-shot method. Nevertheless, 1917 and Birdman are more than just the one-shot gimmick. Both contain incredible performances and a moving story, with the cinematography serving the story effectively and vice versa.

As any film snob will tell you, however, these films weren’t actually done in one long shot. They were instead the result of sneaky editing tricks that have been used since the days of Alfred Hitchcock. In his 1948 film Rope, Hitchcock wanted to emulate the flow of the play it was originally based on by making it appear as one long take. To do this in reality was impossible with the limitations of the time, so instead, Hitchcock devised clever tactics to mask the cuts, such as a color match with a character’s dark coat. Techniques like this are still used in the industry today; hiding cuts behind a block of color is one of the techniques used in both Birdman and 1917. Motion blurring uses the same principle, camouflaging a cut with a quick movement rather than a flat block of color. By combining all of these illusory tricks, and adding in a hefty amount of planning and choreography, Mendes and Iñárritu took us across a battlefield and a city in one, fluid motion.

Movies Like ‘Boiling Point’ and ‘Russian Ark’ Are Real One-Shot Films

Of course, another way to make a film look like it was done in one shot is to do it in, well, one shot. The real deal is newer than the illusion, but authentic one-shot films are possible now with digital cameras, rather than the 10 minutes worth of film Hitchcock had. Now that we have the technology, it’s possible — but by no means simpler — to make movies in one continuous motion. Two films that do this masterfully, but in opposite ways, are the 2002 experimental historical piece Russian Ark, and the 2021 kitchen nightmare Boiling Point.

Boiling Point, directed by Philip Barantini, had the perfect conditions to be done in one shot. An intimate setting of a real restaurant in London was chosen, making the audience feel like a fly on the wall of this high-tension working environment. The single, closed-in location also meant a smaller cast, which made it easier to rehearse, direct, and choreograph. The camera follows stressed-out sous-chefs and exasperated waitstaff around the single building in one continuous shot, with the claustrophobia adding to the stress the audience and characters feel. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they were only able to do four of the eight planned takes for this film, but thanks to the teamwork and endurance on display by the small team, they managed to make one of the best dramas of 2021.

Related

From ‘Birdman’ to ‘Extraction’: 13 Best “One-Shot” Scenes in Movie History

One of the hardest shots to implement and these films do it perfectly!

Shooting one continuous take in a restaurant is difficult enough. Russian Ark director Alexander Sokurov had his work cut out for him when giving us a grand tour of both Saint Petersburg’s Winter Palace and the history of Russia. Using an unbroken Steadicam sequence shot, Russian Ark had a cast of over two thousand strong, with three orchestras playing within the 33 rooms shown in the Russian State Hermitage Museum. The camera was not the star here, as this production effort was one of trial and error. A single mistake would cause the production to stop, reset, and try again. According to the documentary In One Breath: Alexander Sokurov’s Russian Ark, there was only enough daylight and battery for four takes of the film, and it was the very last one that ended up being a success.

Single Shot Films Are Impressive Feats of Planning and Masterful Cinematography

Between real one-shot films and fabricated ones, there should be no argument as to which format is better. Just because a film wasn’t shot in one take doesn’t make it an inferior project, and just because a film uses a complicated technique to present its story doesn’t make it a cheap attempt at grabbing an Oscar. Whether clever editing is used or just a cameraperson with very tired arms, one-shot films in both forms require careful and methodical planning to pull off. Consistency is one of the most important things to keep note of when learning about filmmaking, and it’s also the biggest chore. Keeping watch of every detail to ensure that frames shot hours, days, or even miles apart seamlessly flow together is a feat in and of itself.

Without that excruciating attention to detail both in front of the camera and in the editing room, none of these films would work as brilliantly as they do. Everyone working on the project must be in total sync, and one-shot films are the perfect example of making a story truly come alive right in front of the audience’s eyes.