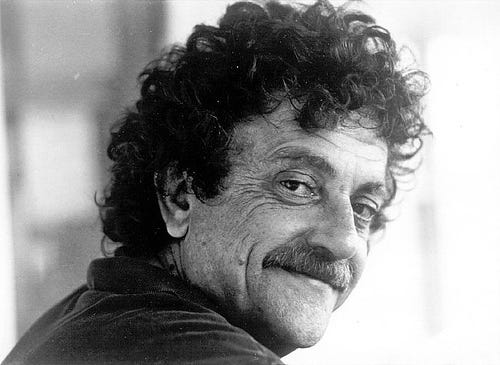

It’s November 11, which is Armistice Day, marking the end of World War I, and also it’s Kurt Vonnegut’s birthday — his 101st! As ever, we’ll start with this wonderful quote about the holiday, from Vonnegut’s 1973 novel Breakfast of Champions (Amazon links in this article give Wonkette a small cut of each sale):

So this book is a sidewalk strewn with junk, trash which I throw over my shoulders as I travel in time back to November eleventh, nineteen hundred and twenty-two.

I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy, and when Dwayne Hoover was a boy, all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans’ Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is.

It’s just such a wonderfully Vonnegut-y quote, for all the terrific reasons there are to love Vonnegut: The short, clipped sentences. The backwards time travel. The affectation of spelling out the year. The “men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind” — Jesus, that’s a lovely line!

This year, I’m going to try to use Vonnegut’s writings about war, particularly his masterpiece, Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) as a lens to think about Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza — with of course the caution that he’s not here to say anything about it himself, so the best we can do is extrapolate, and that can be risky.

I can tell you at the outset that we can’t look to Vonnegut for a solution, sorry.

A month and four days ago, Hamas terrorists killed about 1,200 people in Israel (a downward revision announced today, from 1,400, as if that makes the slaughter any less horrifying). Among the victims were entire families, babies, and young people attending a hippie music festival and dancing all night.

Since Vonnegut remains popular worldwide, maybe some of those killed or dragged away as hostages were fans of Vonnegut’s famously playful dictum, “I tell you, we are here on Earth to fart around, and don’t let anybody tell you any different.” It came from a 1996 essay in which he also said, a bit less famously, “We’re dancing animals. How beautiful it is to get up and go do something.”

It’s a beautiful thought until someone brings AK-47s and grenades to the dance.

In response to that horrific attack, Israel blockaded all of Gaza, cut off electricity and water, and set to work shelling and bombing the hell out of the tiny strip of land, with the intent of eliminating Hamas altogether. The Israeli government justifies the incredible death toll — more than 11,000 and constantly climbing — by pointing out that Hamas hides its fighters and tunnel networks in densely populated civilian areas.

U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres recently called Gaza “a graveyard for children;” at least 4,100 children had died when he said that five days ago. Palestinian civilians were told to evacuate northern Gaza for the south, which Israeli forces also bombed relentlessly. We can only imagine what Kurt Vonnegut would say about that.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and others point to WWII, when the allies made no bones about wiping out entire German and Japanese cities that had any kind of military significance at all. After the war, Gen. Curtis LeMay said of Allied strategy,

There are no innocent civilians. It is their government and you are fighting a people, you are not trying to fight an armed force anymore. So it doesn’t bother me so much to be killing the so-called innocent bystanders.

Robert McNamara later said, in the Erroll Morris documentary The Fog of War, that LeMay had confided to him that “if we’d lost the war, we’d all have been prosecuted as war criminals. And I think he’s right.”

Slaughterhouse-Five is Vonnegut’s attempt to reckon with his own war, when he survived the British firebombing of Dresden in February 1945, an attack officially justified because Dresden was a rail hub and therefore a military target. Incendiary bombs created a vast firestorm, wiping out the city and killing between 25,000 and over 100,000 civilians. No one knows. Vonnegut and some other American GIs captured by the Germans survived only because they were locked underground in Schlachthof-Fünf, a former slaughterhouse for pigs.

Vonnegut throws in a lot of science fictiony tropes, like how his protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, occasionally comes “unstuck in time,” which may be literal time travel or a perfect metaphor for PTSD, or both. But as Salman Rushdie wrote to mark the novel’s 50th anniversary, Slaughterhouse-Five

is a great realist novel. Its first sentence is “All this happened, more or less.” In that nonfictional first chapter, Vonnegut tells us how hard the book was to write, how hard it was for him to deal with war.

Vonnegut tells us in that chapter how Mary O’Hare, the wife of one of his war buddies, exploded at him when he mentioned he was working on a book about his wartime experiences, exclaiming, “You were just babies then!” and predicting Vonnegut would just ignore that and write a novel that could become another heroic war movie that would make war seem “just wonderful, so we’ll have a lot more of them. And they’ll be fought by babies like the babies upstairs.”

So I held up my right hand and I made her a promise: “Mary,” I said, “I don’t think this book of mine will ever be finished. I must have written five thousand pages by now, and thrown them all away. If I ever do finish it, though, I give you my word of honor: there won’t be a part for Frank Sinatra or John Wayne.

“I tell you what,” I said, “I’ll call it ‘The Children’s Crusade.'”

She was my friend after that.

And yet the massacres go on. In other writings, Vonnegut said that the United States and its allies had to go war against Germany and Japan, but that too was tragic in its own way, as he noted in an interview a year after 9/11. He noted that US drones — “our unmanned kamikazes” — were inflicting horrifying casualties,

“But this has become quite acceptable in modern warfare apparently — to kill a hell of a lot of innocent people in the process of getting one bad guy. And also I think this war is a very bad idea because it will never stop.”

One of the great American tragedies is to have participated in a just war. It’s been possible for politicians and movie-makers to encourage us we’re always good guys. The Second World War absolutely had to be fought. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. But we never talk about the people we kill. This is never spoken of.

The Afghanistan war lasted until August 2021, outliving Vonnegut by 14 years, three presidents, and tens of thousands of civilian deaths. When you’re right, you’re right.

Vonnegut also worried, following the first Gulf War in 1991, about how attitudes toward war have evolved in frightening directions since the war he lived through:

“We have become such a pitiless people,” Vonnegut lamented. “And I think it’s TV that’s done it to us. When I went to war in World War II, we had two fears. One was we would be killed. The other was that we might have to kill somebody. And now killing is Whoopee. It does not seem much anymore. To my generation, it still seemed like an extraordinary thing to do, to kill.”

The Hamas terrorists, however young they may have been, don’t seem to have had any doubts about the justice of their slaughter of Israelis, including children. The IDF, operating so far mostly at a distance like civilized technological nations prefer, seems more coldly unaffected by empathy for the civilians its munitions land on.

Slaughterhouse-Five closes with the end of WWII; the German army heads east to fight the Russians. “And somewhere in there it was springtime,” Vonnegut writes, and one day the war is over, all the guards gone. Birds again can be heard, asking, “Poo-tee-weet?”

But Vonnegut has no answers, really, except perhaps Eliot Rosewater’s advice to newborn twins in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater:

Hello babies. Welcome to Earth. It’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter. It’s round and wet and crowded. On the outside, babies, you’ve got a hundred years here. There’s only one rule that I know of, babies- “God damn it, you’ve got to be kind.”

Perhaps some Palestinian or Israeli teenager will survive to write the great novel about the horror and stupidity of this war in another 20 years. Wars are often as good for literature as they are for innovations in the technology of killing and the technology of healing, though the latter always runs well behind the former. There are far more ways to destroy the human body than to repair it.

Vonnegut was as mystified as any of us about how to actually get humans to treat each other decently and with justice, but seeing the humanity in other people has to be a starting point. Vonnegut thought that humanism and democratic socialism might be good starts, and maybe he was on to something there.

Too many babies have died for no good reason. As Israelis mourn the worst mass murder of Jews since the Holocaust, and as the IDF daily converts more and more parts of Gaza into Dresden, we’ll close with one last quote, this time from Jailbird (1979):

I still believe that peace and plenty and happiness can be worked out some way. I am a fool.

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please subscribe, or if a one-time donation works better for you, here’s the button.

Also, if you’re shopping at Amazon anyway, this portal button gives a small cut of sales to Wonkette, as do the links below.

Wampeters, Foma & Granfalloons

As ever, we end with Eric Bogle’s “And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda,” another reflection on the terrible waste of war:

OPEN THREAD!

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)