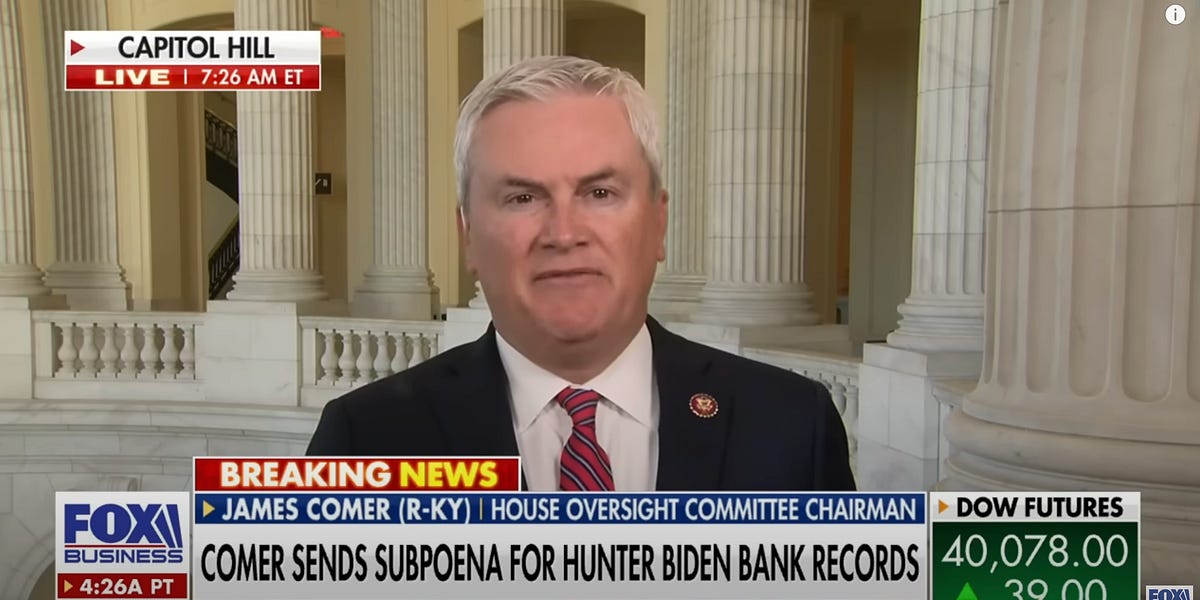

Email remains a powerful and cost-effective tool for content delivery and marketing offers, despite frequent predictions to the contrary. But acquiring new email addresses requires a lot of effort, which raises the question of return on investment. How much can you afford to spend on a new email address?

Let’s start with a very simple calculation:

Value = revenue from emails ÷ deliverable email addresses

For example, if your email program brings in $100,000 and you have 100,000 deliverable names on your list, each email is worth one dollar.

That’s overly simplistic and it immediately raises two key questions: How do you calculate email revenue, and over what time period?

Calculating email revenue

To determine how much revenue you get from your various email campaigns, list all the possible ways your business generates revenue through email. This may include:

- Ad revenue from content emails.

- Ad revenue from web traffic that was generated by an email campaign

- Direct sales, including product sales, subscription sales, events, etc.

- Affiliate sales.

- Lead generation.

- Data from surveys.

You’ll never get it exactly right. Attribution is a fuzzy science. For example, one of your content emails that sends someone to the website might result in that person picking up your publication from the newsstand. You can’t track that.

But you can come up with a reasonable estimate of your monthly revenue from each source or any others that apply to your business.

What is the expected life of an email address?

Now that you know how much you make from a typical email address in a given month, you must calculate how many months an email will likely stay active on your list.

Remember that “active” means more than that the email is deliverable. You want to find the people who read and interact with your emails.

Such a calculation ought to be an out-of-the-box standard for any email service provider (ESP), but it’s not. It’s complicated by many factors, which I’ll discuss below. But here’s a quick and dirty way to get a reasonable estimate.

The average longevity of an email address is 1 divided by the loss percentage.

So if you lose 5% (0.05) of your list every month, your average customer will stay on your list for 20 months. The calculation is:

1 ÷ 0.05 = 20 months

Now it gets complicated

I won’t blame you if you stop right here because if you go on, you run the risk of analysis psychosis. But if this topic interests you, and you’ve been paying attention, I’m willing to bet that you have an inner interlocutor who has been screaming a lot of questions at you.

- What about segmentation?

- Am I supposed to treat every email address the same?

- When calculating revenue, do I use the list price or the lifetime value of a subscription sale or customer?

Right. And the more you think about it, the more questions will occur.

Pursuing all those questions is the path to madness. There’s an entire wing at the hospital full of people who have tried to answer them.

You’ll have to get comfortable with a rough estimate that isn’t as precise as you’d like.

By the way, now would be a good time to refresh your recollection of the distinction between accuracy (getting near the right answer) and precision (how close all your measurements are to each other).

A precise answer to this question is impossible. You’ll never get the same answers from multiple methods. But something like accuracy might be achievable.

If you take my advice and avoid the slippery slope to madness, you’ll still have to answer for your number, which means you’ll need to be ready for the tough questions. The next section will prepare you.

Fudge factors

Any given email list is like a dragnet that pulls in fish, mussels, crabs, old fishing lures and beer cans. The quality, and therefore the value, of each email varies dramatically.

You have:

- Company emails

- Personal emails

- Emails you acquired with a paid transaction

- Emails somebody gave you to get a free white paper

- Emails from append services

They don’t all have the same value. But it’s hardly possible, and certainly not worth your time, to separate them all and do all the above calculations for each group.

For example, can you separate company and personal emails, and if you are, can you get reports on the different click-through rates for each category? Probably not.

So what do you do?

You give yourself a discount.

Let’s say you use the basic calculations above and decide that a new email address is worth $2. You also know that when people sign up to get your white paper, they’re very likely to give you their junk email, which will be on the low side of that average. So when someone asks, “how much can I afford to spend to collect emails for my free white paper effort,” you can’t in good conscience say $2. Maybe they’re only worth $1 each.

On the other hand, an email address you get when someone submits a question (and wants an answer) is far more valuable. Maybe that one is worth $5.

So you make a list of your sources.

- Sign-ups for email newsletters.

- Emails that come with a paid subscription.

- Emails that come with a non-subscription purchase.

- Emails from lookup services.

- Emails from government lists.

- Emails from business cards collected at the annual conference.

- Given in exchange for a free white paper.

Rank them from least to most valuable. If possible, try to get a sense of what portion of your list comes from each source.

For example, let’s say I was able to create a chart like this.

| Source | Value | % of database |

| Emails from government lists | 40% | 10% |

| Given in exchange for a free white paper | 50% | 15% |

| Emails from lookup services | 70% | 10% |

| Sign-ups for e-newsletters | 100% | 35% |

| Emails from business cards collected at the annual conference | 125% | 2% |

| Emails that come with a non-subscription purchase | 175% | 25% |

| Emails that come with a paid subscription | 200% | 3% |

With a little work in Excel and some high school math skills, you should be able to assign a dollar value to each category based on the overall (average) number you calculated above.

This is far from perfect, because you’re just guessing at the “value” column. But at least you have some numbers with some assumptions, and you’ll be able to answer probing questions from the C-suite. (Provided they remember high school math.)

Understanding the true value of a new email address is vital for effective email marketing strategies. You can’t afford to spend the “average value of an email” on campaigns that get low-quality results. You also can’t afford to scrimp on campaigns that bring in your top performers.

Following these steps — or something like them — can give you the confidence to know how much to spend for different types of email acquisition efforts.

Dig deeper: How to send more emails and grow your subscriber list

Get MarTech! Daily. Free. In your inbox.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily MarTech. Staff authors are listed here.