This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

“Deeper meaning resides in the fairytales told to me in my childhood than in any truth that is taught in life,” reads a quote by Friedrich Schiller that I have pinned to a bulletin board in my office. It puts into words a sentiment and a feeling that I started to feel more and more as I’ve grown older, especially aging out of my teens and into my early 20s. I was always raised with the philosophy that you’re never too old for a fairytale, and while it was something I knew in the back of my mind to be true, I’d learn that fairytales hold just as much power in adulthood as they do in childhood.

Maybe it was the burgeoning anxiety disorder I’d be officially diagnosed with as a twentysomething that made me cling to the seemingly simplistic stories told to me in childhood, but as a literature student I soon came to learn that fairytales and their wisdom are definitely not just for children. I happened upon an elective all about fairytales in college, and it remains one of the best post-secondary classes I ever took. We’d read passages from a book by Bruno Bettelheim from 1976 called The Uses of Enchantment of which, despite my best efforts, I could not locate a copy at the time. Then, just a few months ago, I happened upon a copy at a second-hand bookshop, and I’ve seldom ever been so happy to finally see a book in the flesh.

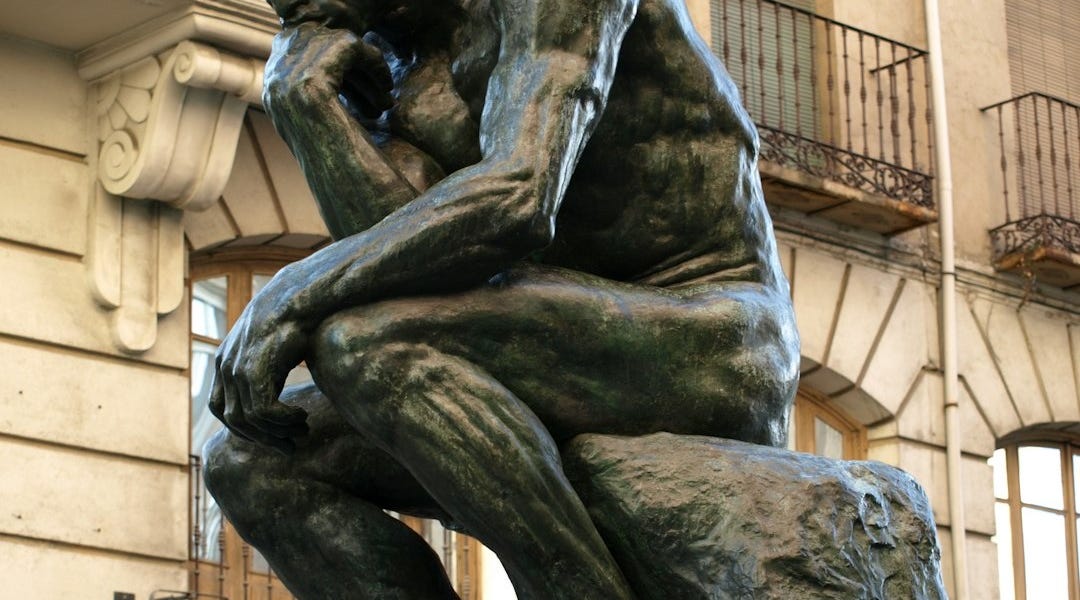

Bettelheim’s hypothesis was simple: taking into account moral objections to fairytales by some parents and their schools of thought, children need these often dark stories to make sense of the dark forces that control and dominate their world, especially at a young age when they will most likely have no other language through which to process these anxieties. Beyond that, he stresses the importance of fairytales not just for their lessons and aesthetics, but as literary works of art: “The delight we experience when we allow ourselves to respond to a fairytale, the enchantment we feel, comes not from the psychological meaning of a tale (although this contributes to it) but from its literary qualities — the tale itself is a work of art. The fairytale could not have its psychological impact were it not first and foremost a work of art.”

But as I continued reading The Uses of Enchantment, most of which I was encountering for the first time in full, I was realizing, perhaps for the first time, a part of myself growing up being articulated between the lines: “Even if a parent should guess correctly why his child has become involved emotionally with a given tale, this is knowledge best kept to oneself.” Sure, every child probably develops an attachment to something so deep that they aren’t mature enough to properly verbalize. But I felt this exact attachment to fairytales growing up, a sense of myself that couldn’t be explained to adults around me let alone myself yet. “Fairytales, unlike any other form of literature, direct the child to discover his identity and calling, and they also suggest what experiences are needed to develop his character further.” Did fairytales know I was queer before I did?

It’s not like I hadn’t thought of this connection before, between my passion for fairytales and my queerness. I’ve often found it laughable the ways that effeminate young boys are left out of the cultural conversations surrounding the morality and purpose of fairytales for children. Historical princesses are bad role models for our daughters: they teach them to wait around for a man to save them. However not true that may be, what did my love of princess stories say about me growing up? That my gravitation towards the feminine meant I’d grow up to be gay? I did, of course, but what it represented for someone like me went deeper than that: princess stories like Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty symbolized less the patriarchal oppression through which they are often interpreted today and more a quiet, budding sense of empowerment — teaching me very young how to fight for my own sense of femininity, however large or small, in a culture that was prepared to whip it out of me by any means necessary.

“The fairytale is therapeutic because the patient finds his own solutions, through contemplating what the story seems to imply about him and his inner conflicts at this moment in his life,” wrote Bettelheim. The author, a once-renowned psychologist, was certainly not the last to suggest this philosophy that fairytales teach us not only that dragons exist but that they can be beaten, to paraphrase Neil Gaiman. But his notion that these stories help us find our own solutions, just as Dorothy must learn herself that she’s always had the power to go back to Kansas, is a profound one that ultimately extends to people of different races, classes, genders, and identities. Not to excuse the rampant heteronormativity ingrained in classic fairytales, but the concept remains true.

But one of Bettelheim’s main arguments throughout The Uses of Enchantment remains that fairytales provide an avenue through which a child can understand themselves better. He describes this as a process of “bring[ing] some order into the inner chaos of his mind,” which is a “necessary preliminary for achieving some congruence between his perceptions and the external world.” Of course, the wisdom of fairytales extends to children of all shapes and sizes, not just those who may grow up to be queer. But the ways in which my readings of fairytales growing up came to greatly influence my queerness were only reinforced by Bettelheim’s thinking.

“I think the more interesting and truthful take on why so many queer people live in the creative space is that we are forced to think of the world in terms of symbols and metaphors from a very young age,” David Crabb, author of the memoir Bad Kid, told me. “Sexual desire is base in all of us. So the idea that this core part of our personas is denied (or at least not nurtured by heteronormative culture) means that we find alternative ways to ‘say things’ at a very young age; to tell stories that aren’t entirely ‘true’ because we can’t actually say the thing out loud.”

These alternative ways of saying things and telling stories takes shape differently in every queer person, but the base desire is still the same. For me, it was only once I finally got to read more of Bettelheim’s book that I was able to complete this link that exists within me between myself and fairytales. It’s healing, in a way, to give a voice and recognition to things you weren’t able to say out loud to yourself growing up. And fairytales did that for me. So don’t ever deny your children of them, I beg of you.