Growing up in the 2000s and 2010s, big tech made some big promises: Everything would be disrupted, streamlined, simplified. We’d be able to hack our lives to perfection, and doing so would make everything cheaper, to boot.

For a while, the promises seemed to pan out. At least in certain sectors. Travel—flights, accommodations, transportation—was democratized, with more people able to afford to go to more places and post the photos to prove it on Instagram. Food from local restaurants and grocery stores could be delivered for free right to your front door. Designer clothes could be rented for a fraction of the cost of buying retail and returned with ease, after, again, the requisite shot for social media.

But into the 2020s, the sheen of the accessible luxury tech era has faded. The companies that once subsidized a certain urban lifestyle failed to actually turn a profit, and so the little luxuries—Uber rides home from the bar, unlimited workouts at boutique fitness studios—that were once affordable are no longer so.

And thanks to a combination of rampant inflation, stagnant wages, and recession fears, customers are already feeling their budgets squeezed. So long, cheap luxury; hello, expensive reality.

The free ride is over

Propped up by plenty of venture capital funding and favorable market conditions, many tech startups were able to offer customers (frequently depicted as young urbanites but in reality spanning all generations) premium goods and services at steeply discounted prices, for a decade. It was easy for a certain type of consumer to enjoy a luxury lifestyle on a discount, including routine restaurant delivery, car rental on demand, and even discounted pre-portioned meals for the aspiring foodie who didn’t know how to cook.

Their wages might not be rising and their student loan debt might be overwhelming, but they could still rent out a country house for the weekend and convince themselves it was all working out as it should.

“We really did get spoiled,” says Charles Lindsey, associate professor of marketing at the University at Buffalo School of Management. “Shareholders were really subsidizing those low prices for these companies to build their markets.”

The markets have been built, but the promotional ride is over now—and the experts aren’t surprised. The demise of these types of services and funding models was foretold; prices have been inching up for years.

Now, though, the full bill is harder to bear for many consumers, thanks to a confluence of factors: the free money that allowed companies to subsidize these lifestyles without actually profiting has dried up as interest rates have risen. Inflation has taken its toll on everything from housing to gas to groceries to travel. The COVID-19 pandemic constrained supply but built up demand that is now bursting, particularly in travel. The economic winds have shifted.

Though the rise of these small luxuries has been dubbed the “millennial lifestyle subsidy”—used to paint Generation Y once again as entitled spendthrifts—the truth is all generations used and enjoyed these premium services, says Lindsey. And no one is happy that everything is now more expensive.

But the end of these subsidies is still more resonant to the generations entering the workforce in the 2010s and beyond than to their parents or grandparents. Not because millennials are necessarily more reliant on them, rather, because cheap travel accommodations and cashmere-on-demand created an illusion of wealth for college-educated, supposedly upwardly mobile young adults who frequently had to take on multiple jobs to pay their monthly bills. As debt-strapped professionals flocked to cities that promised higher wages, these cheap luxuries enabled millennials to enjoy some of the fruits of their labor, even if they couldn’t actually afford the rent.

The rent has become even more unaffordable for twenty- and thirty-somethings who didn’t (or couldn’t) leave higher-cost-of-living cities for the suburbs at the same rate as their parents. In the past cheap luxuries offered some solace, but now millennials’ lack of real wealth feels even more pronounced.

These younger generations didn’t enjoy the housing and education subsidies their parents and grandparents received post-WWII; they have navigated two once-in-a-generation economic shocks already—and a pandemic. Now, they can’t even get a cheap ride to the airport.

Premium services at discount prices was never sustainable

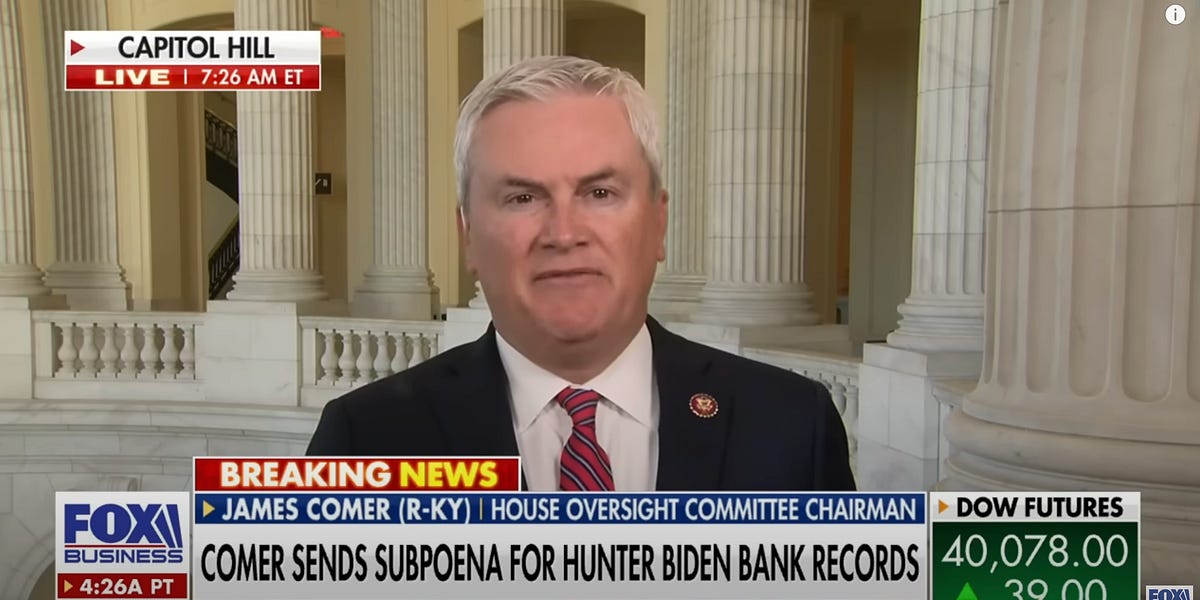

The poster boy of this subsidized excess is Uber—when it was good, it was great. But it’s no longer great. Trips cost significantly more than they did even a year or two ago: The average price of a rideshare trip in the U.S. cost 34% more in November 2022 compared with November 2019, according to market research firm YipitData.

Just a few weeks ago, an Uber ride from the New Orleans airport to my accommodations was priced at $73. A cab, on the other hand, charged a flat fee, which was half the price, just $36. My traveling companion and I didn’t even have to wait for the cab to arrive, then try chasing it down within the 2-minute timeframe given to find our driver; there was a queue of them ready to go.

Airbnb is another good example. When it began, it offered more affordable and unique accommodations for travelers hungry for a one-of-a-kind experience. Now, with hosts tacking on fee after fee and leaving a to-do list of cleaning tasks for guests to tackle before they leave, many people are questioning whether it’s worth the hassle. If you’re going to pay for a cleaning service, and you’re prohibited from having friends over for drinks, you may as well stay at a hotel that guarantees fresh sheets and plush towels, and you’re not required to take the trash out when you’re rushing for the airport.

Companies are slashing rewards and loyalty programs to focus on profitability, says Lindsey. Loyal Dunkin’ Donuts drinkers were outraged when the coffee chain changed its rewards program so that customers have to spend more than double what they previously did—now $90, up from $40—to earn a free latte. A more elite example, according to Lindsey: Delta Airlines changed its rewards program in 2023. To attain the highest rewards status, passengers must spend $20,000 this year (in addition to mileage requirements), compared to $15,000 last year—a roughly 33% increase.

Outside the travel sector, apps like Poshmark and Depop once brought affordable secondhand and vintage clothing and accessories to the masses. Now, resellers have taken over, pricing used goods, from “vintage” fast fashion T-shirts to well-worn ankle boots, at retail price or even higher. Thrift stores have also been increasing their prices, seeing an opportunity to make more off of the reseller scouring racks IRL for goods to hawk online. The result? People who actually can’t afford to buy clothing anywhere else are getting priced out.

Doordash and Seamless promised to deliver food from any restaurant or convenience store, often without a delivery fee attached. Now, fees add up quickly, as restaurants charge for service and delivery, as well as tips for the delivery workers themselves. Restaurants inflate their menu prices to recoup the cut taken by the delivery app.

For some customers—those who are disabled or have limited mobility for other reasons—these are still great services. But in big cities, those millennials who used to not think twice about placing an order from their phone, it now makes more sense to simply walk a block or two to the nearest takeaway spot, or pick up the phone and place an order the old fashioned way.

Disruption leads to fewer options

Turns out, the old fashioned way worked well enough for a lot of the experiences tech promised to disrupt.

And now that all of these services cost more, customers are realizing the quality isn’t quite up-to-snuff. Ordering sub-par delivery from a local spot is okay when you get free delivery and a discount; it becomes less attractive when the freebies go away, quantities shrink, and restaurants pass on increasing food costs to their customers.

Likewise, a redeye flight on a budget airline is tolerable when it costs less than the cab ride to the airport. But when every flight costs hundreds of dollars for a grueling, dehumanizing experience—that frequently includes canceled or delayed flights—and the airline loses your bag, travel for travel’s sake becomes less appealing.

Unfortunately, the old fashioned way doesn’t exist anymore in many industries—it was killed off by big tech. Many restaurants that couldn’t keep up with rising food costs and delivery platform fees are no longer in business; those that are are splitting their profits with a middle man who doesn’t do much but make discovery for some customers a little easier. To keep up with the accelerated trend cycles perpetuated in part by secondhand shopping and resale apps—and exacerbated by social media—clothing quality in general has been decimated. Even when you’re shelling out for a “quality” garment, you might find it’s made 100% of synthetic materials. Uber and Lyft, buoyed by 10 years’ worth of investor subsidies, effectively killed off taxis in some markets across the country, says Lindsey.

It’s hard for consumers to “extract a penalty” against these companies that dominate the market, says Lindsey. “We’re going to have to get used to increased prices, at least in the short term.”

Of course, not all luxury lifestyle accoutrements are going away. Consumers are still spending on clothing, food, travel, and experiences—but now they’re usually paying full price. And who can afford that?