[ad_1]

King Arthur and the stories surrounding his court have been popular for nearly 1,000 years, ever since Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote History of the KIngs of Britain. Whether Arthur was a real person has never been as important as the stories surrounding him; stories given a major boost by Sir Thomas Mallory‘s 15th century Le Morte d’Arthur.

These legends have inspired poems, novels, operas and, of course, films. The following includes musicals, comedies, romances and attempts to get to the historical core of the legend, demonstrating the hold the story still has on us to this day.

‘King Arthur’ (2004)

In King Arthur, Artorius (Clive Owen) and his small troop of Sarmatian cavalry are preparing to withdraw from Britain with the rest of the Roman army when they are given one last mission – to secure the safety of a Roman family. From that point on, matters get very complicated quickly, involving marauding Saxons, vengeful Celts (called “Woads” in the film), and naturally, fate in the shape of Guinevere – a Woad played by Keira Knightley.

This is a brave attempt to set the Arthurian legend in a fixed historical period, and makes a convincing argument that the legend is based firmly on a real person. If the story itself feels a little formulaic, the film still has some great set pieces to keep an audience engaged, and holds together better than The Lost Legion (2007), a similarly themed but less successful film.

‘Prince Valiant’ (1954)

There’s history, and then there’s Hollywood History, a flashier, cleaner and thoroughly modern version of the past. Arthurian films from the 50s, such as Knights of the Round Table (1953), are an example of this. The industry also had the habit of inventing new characters to add to the panoply of already existing Arthurian knights, damsels and villains. In this case, Hollywood took a shortcut and kidnapped a character already invented by comic strip writer and artist Hal Foster.

Prince Valiant, starring a youthful Robert Wagner, is an excellent example of Hollywood History, great fun but slightly less historical than an episode of Black Adder. In the end, the film’s standout character isn’t the athletic Prince Valiant but his nemesis, the treacherous Sir Brack, played with great gusto by James Mason.

‘Sword of Lancelot’ (1963)

An underrated actor (as well as an Olympic-class fencer), Cornel Wilde had an erratic – if long – Hollywood career. After creating his own production company with wife, Jean Wallace, he made a series of films including Sword of Lancelot. Wilde co-wrote, co-produced, directed and starred in the film.

A genuine attempt to break away from some of the more colorful Hollywood Histories, the film was grittier, bloodier and sexier than most of the Arthurian films that had come before it (Wallace played Guinevere, resulting in some real onscreen chemistry between the star-crossed lovers). It almost feels genuinely medieval, and has some convincingly gory action scenes.

‘Camelot’ (1967)

One of the most successful musicals on stage or screen in the 1960s, Camelot is the perfect example of the Arthurian legend’s adaptability to different mediums and different genres; helped along by a bagful of nifty songs by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe.

Based on T. H. White‘s The Once and Future King, it plays up the romance and tragedy of the love triangle between Arthur (Richard Harris), Guinevere (Vanessa Redgrave) and Lancelot (Franco Nero). The movie is three hours, and these days more famous for its music, but Camelot actually makes for a decent drama.

‘Monty Python and the Holy Grail’ (1975)

Regarded on both sides of the Atlantic as one of the funniest comedies ever made, Monty Python and the Holy Grail almost never got off the ground because no studio would produce it. In the end, the film’s minimal budget (which might explain the use of clacking coconuts instead of real horses to make the sound of galloping hoofs) was funded from a variety of sources, including rock bands like Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd.

The movie follows a series of thematically connected sketches by the Monty Python crew rather than a continuous narrative. King Arthur and his squire, Patsymake their way through a surprisingly convincing medieval landscape in search of the Holy Grail. The fact they never find the Grail is one of the jokes. Filled with a good deal of whimsy as well as humor, this is a great King Arthur film.

‘Excalibur’ (1981)

John Boorman‘s Excalibur is a spectacular if not entirely convincing retelling of the heart of the Arthurian legend: the relationship between Arthur (Nigel Terry), Guinevere (Cherie Lunghi) and Lancelot (Nicholas Clay), a triangle that mirrors the dynamics between a king, his subjects, and the land itself.

Despite both being based on Mallory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, Excalibur is not Camelot without the music. Boorman’s film carries greater dramatic weight, and consequently the failure of kingship has greater dramatic consequences. The battles scenes are visceral, and Arthur’s death at the hand of Mordredhad audiences shuddering in sympathy.

‘A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court’ (1949)

Based on Mark Twain‘s 1889 novel, A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, the movie of the same name stars Bing Crosby as the protagonist Hank Marvin. Hank is the eponymous Yankee who finds himself in 6th century Britain ruled by an aging King Arthur. With modern know-how he rises in Arthur’s esteem to a position of some influence, arousing the jealousy of Merlin and Morgan le Fay.

Unlike the original novel, the films ends on a somewhat positive note, with Hank out-singing and outmaneuvering his enemies. If its title wasn’t so long this film could be used as a synonym for schmaltz. But schmaltz has its place, and done well still makes for satisfying viewing. In fact, this film is not only satisfying, it’s also fun and memorable.

‘The Fisher King’ (1991)

Directed by Terry Gilliam – one of the two Pythons at the helm of Monty Python and the Holy Grail – The Fisher King takes its premise from one of the stories connected to the Arthurian legend. The wounded Fisher King, whose domain is barren, is waiting for a stranger to save him.

In this modern retelling, set in New York, Jack Lucas (Jeff Bridges) is the wounded king, and Parry(Robin Williams) the homeless, psychologically damaged stranger who rescues him from a beating by street thugs. This action sets in motion a whole chain of events leading to both Lucas and Parry being healed and finding love. The real genius of this wonderful film is its affirmation that simple actions can lead to great changes, and that given a push, hope can produce something real and concrete. In this regard, at least, The Fisher King is the most Arthurian film of them all.

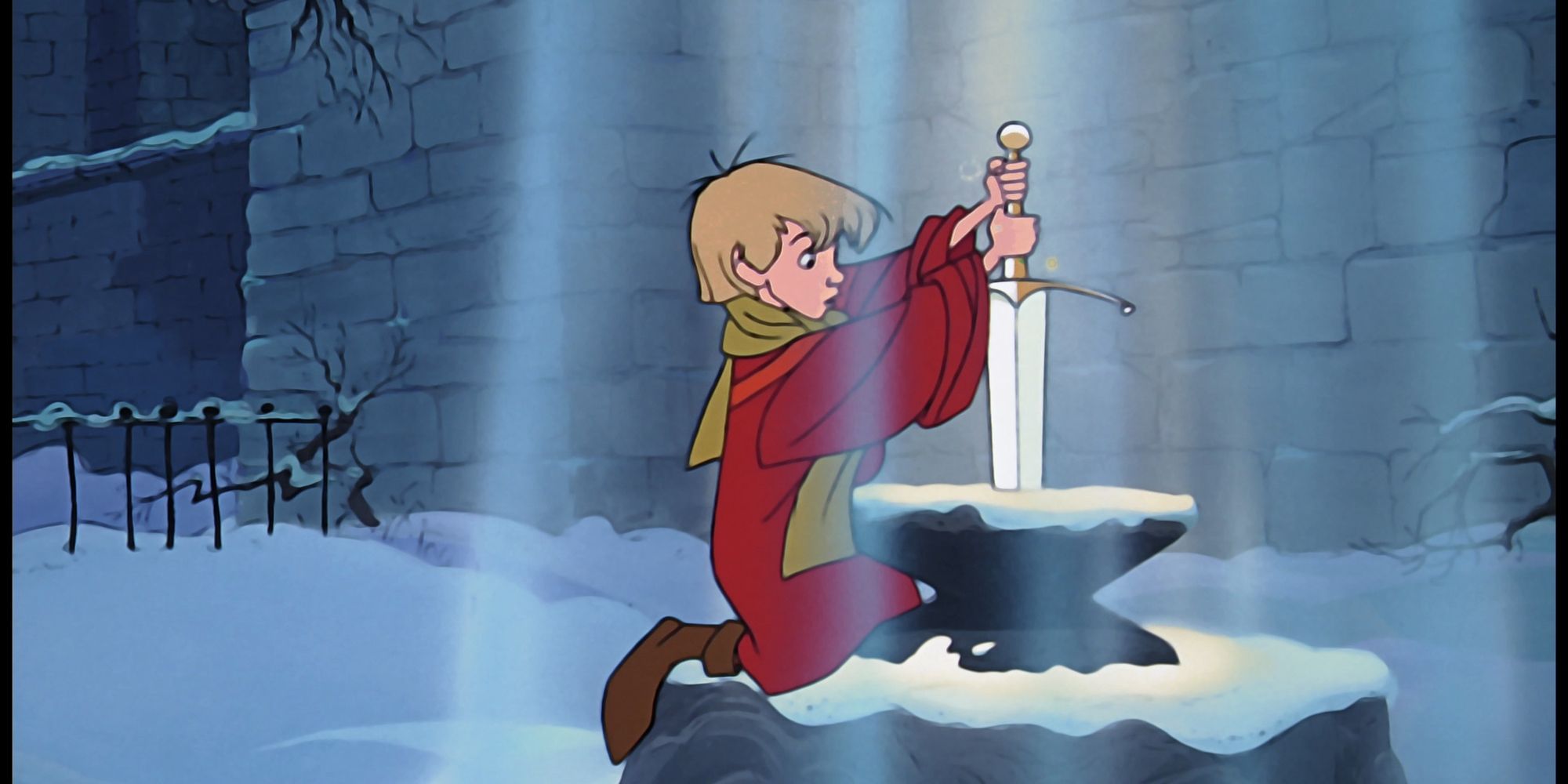

‘The Sword in the Stone’ (1963)

Based on the first book in T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, The Sword in the Stone is basically King Arthur for children. It uses animation, music and comedy to tell the story of Wart – Arthur as a boy – as Merlin teaches him the basics of physics, gravity and flying rather than swordsmanship, horse rising and leadership.

As a children’s film in its own right, The Sword in the Stone works, and one reason for that is the mystique that goes with telling part of the Arthurian legend. As it should be with real childhood, first there comes wonder and surprise and revelation. The darker side of the legend, and of life itself, is properly beyond the scope of this charming film.

‘The Green Knight’ (2021)

With The Green Knight, American director David Lowery has made what feels like a quintessentially British film. The story, based on a 14th century poem, follows the journey of Gawain (Dev Patel) from King Arthur’s court to the Green Chapel where he meets his destiny under the great axe of the Green Knight.

The film is formed as much by its soundscape and landscape as its actors, weaving the real, the illusory and the magical into a narrative where reality always seems just out of reach. At one point, Gawain asked the ghostly Winifred – in whose cabin he temporarily finds refuge – ‘Are you real or are you spirit?’ and she answers ‘What’s the difference?’ Indeed. In a film which strangely gets closest to the mythology at the heart of the Arthurian legend, there is no difference.

[ad_2]

Original Source Link

.jpeg)