Editor’s Note: This article contains mentions of sensitive material including sexual assault.

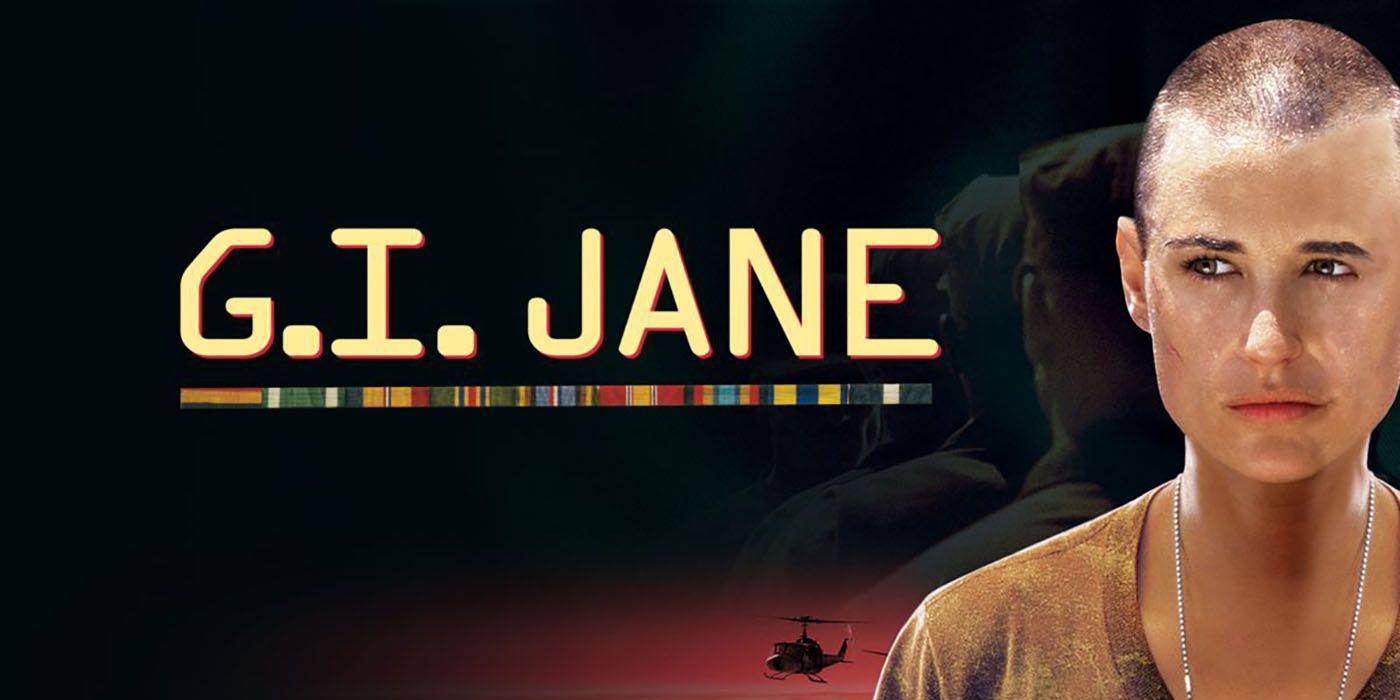

This week marks the 25th anniversary of Ridley Scott‘s G.I. Jane, starring Demi Moore and Viggo Mortensen, a movie many have heard of but few have actually seen. The film follows Moore as Lieutenant Jordan O’Neil, an intelligence officer who has been hand-selected to be the first female officer to enter Navy SEAL training, which the film dubs C.R.T. (Combined Reconnaissance Team). This months-long program is notorious for being the most difficult in the United States Navy and is said to have a 60% drop-out rate. O’Neil enters and is forced to endure not just the arduous training but also a constant barrage of misogyny and derision from her fellow trainees and superiors.

Over the course of the film, O’Neil eventually earns their begrudging respect after going head-to-head with the Master Chief, a U.S. Senator, and opposing soldiers on a critical mission, before finally graduating from training as the first female ever to do so. The movie gained infamy as one of Scott’s worst movies, and Moore even won a Razzie award for her performance despite going through extensive lengths to prepare for the role, including gaining an impressive amount of muscle, shaving her head, and even going so far as to attempt calling the Vice President. Ridley Scott is no stranger to films highlighting strong women — case in point being Lt.Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) from Alien. However, the message of equality this film attempts to convey is completely undone by the way it sexualizes Moore and continuously reinforces the idea that it’s up to women to prove that they’re deserving of basic respect. In doing so, this film alienates the female audience it’s meant to champion.

This film is not without its merits, as it attempts to expose the battle women face when entering spaces drenched in hypermasculinity. Its message is an important and timely one, both in the 1990s and today, and its release came six years after the Tailhook scandal and one year after the Aberdeen scandal. Both incidents are horrific stains on the U.S. military’s history, where female officers were preyed upon and sexually assaulted by their peers and superiors. For anyone who watched G.I. Jane and considers it an unrealistic portrayal, they need only to research these two cases as well as the story of Shannon Faulkner and her experience as the first woman to ever attend and graduate training at The Citadel. During the 1990s, the U.S. military was known as an almost impossible institution for women to safely navigate. Toxic masculinity, rampant militarism, and isolation from the public created a perfect storm of factors that made it easy to objectify and abuse fellow female officers. Ridley Scott’s timely release of this film does a decent job of portraying what it is to be a woman in the Navy in a time and environment where femininity is perceived as an enemy.

Another great attribute of the film is highlighting how oppressors often start to consider themselves oppressed when their victims begin to demand equality. At the beginning of her training, as O’Neil enters the dining hall full of men for the first time, a male soldier angrily proclaims that “he hates to speculate” how she got into the program, but he had to petition for years to get in, and it’s unfair for her to now be able to do so. He is, of course, the first to willingly exit the training. Her superior officer also expresses resentment toward her and other female officers because he must now deal with sensitivity training, the smell of perfume in his office, and heaven forbid, OBGYNs. To the audience, it is clear who is actually being discriminated against; however, equality can often look like oppression to those who previously wielded the power.

From there, the film’s message falls apart and does more harm than good, starting with the blatant and completely unnecessary sexualization of Moore. In a particularly disturbing montage illustrating the middle portion of training, O’Neil is waterboarded for training purposes, an act that typically sees the victim tied down on a moveable plank with a piece of cloth completely covering their head. However, Ridley depicts O’Neil held down by several men with water poured down her throat as the Master Chief holds her mouth open, a scene quite pornographic in nature and its intention reinforced by the next shot. Here we have O’Neil conducting her own strength training in private, doing set after set of pull-ups and one-handed push-ups. That’s not ridiculous. However, the fact that she’s glistening with sweat in short-shorts and a cut-off white tank top with no bra as the camera does its best to get shots of her ass is very ridiculous. No woman in the audience would watch that scene and not see it completely for what it was — a cheap attempt at broadening viewership for the film. On one hand, Scott condemns those who only value women for their bodies, whilst on the other, reinforces exactly that sentiment. In this one montage, Scott reminds his female audience that their worth depends not on how well they can train but on how attractive they look while they do it.

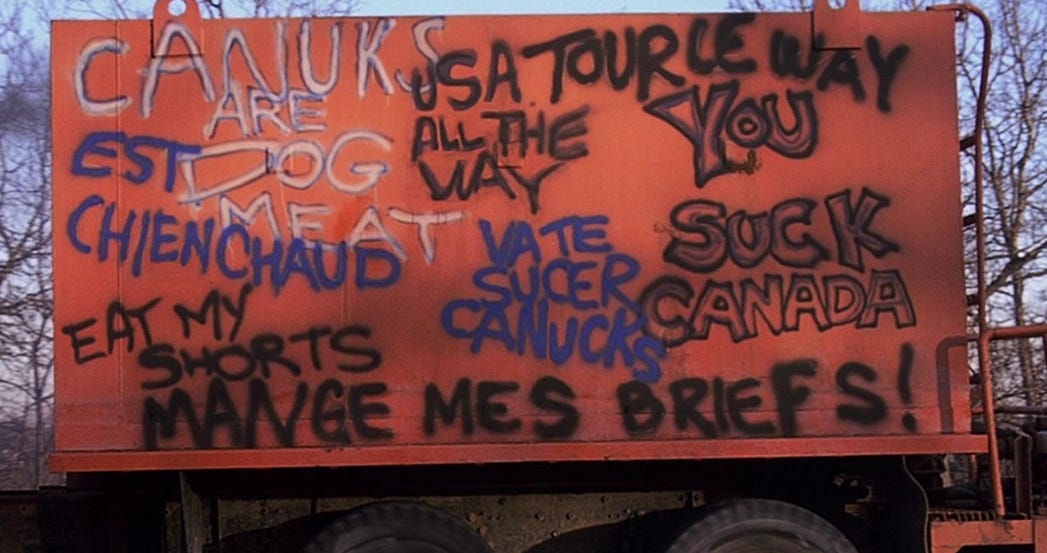

What’s more, O’Neil is only accepted when she embraces masculinity and casts aside anything that can be construed as stereotypically feminine. Before entering training O’Neil is drinking wine during a candlelit bubble bath and by the end, she’s sipping Jim Beam and smoking a cigar. Of course, it’s not wrong for a woman to prefer bourbon to bubbles; however, the film makes it clear that she is only found worthy to be a SEAL because she no longer embodies the characteristics of a “typical woman.” Beaten and bloody, she fiercely tells the Master Chief to “suck my dick!“, a sentiment that promotes a round of cheers from the men in her unit. This is the first time they support and accept her, she’s one of them now. By consistently stating that she wants to be treated like the other men, no more no less, she ensures that no meaningful change is made to make the Navy a safer and more accessible space for women.

The film doesn’t want O’Neil to change an unfair system, they want her to become a part of it. None of the men did any work to alter their way of thinking or behavior, instead, the underlining tone of the film is for women to stop “feeling sorry” for themselves and to do away with ideas of equity completely. The burden of integration rests solely on women and how well they can adapt to the current and broken way of doing things.The cherry on top is the pointed effort to sway the audience into believing that, although the men in O’Neil’s camp have verbally abused, beaten, and sexually assaulted her, at their core, they’re good men and just needed to have their eyes opened a little. Instead, the film chooses Senator DeHaven (Anne Bancroft) to fill the slot of the main antagonist. Though it is a harsh reality that some women can become the strictest enforcers of patriarchal law, it is a disappointing yet unsurprising direction for the film to lead. These men have psychologically tortured and disrespected O’Neil at every turn, only for the film to give them redemption simply for allowing her to exist in their presence. What’s worse is it ends with a teary-eyed O’Neil touched to have the respect of the man who strategically opted to shock and humiliate her by cornering her in the shower and sexually assaulting her during the P.O.W. training. This film is a masterclass in how important it is to have women involved in every step of production. After scratching the surface, G.I. Jane is a two-hour movie where no woman wins. Ridley Scott has created a film where, in the end, it is still unacceptable to be a woman in the SEALS.