This content contains affiliate links. When you buy through these links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Being a woman in ones twenties might feel like walking through fire at times. When we are on the verge of a societal collapse, we can do very little to evade the feeling of being doomed. While nothing alleviates the heartbreaks of that challenging decade, books do in fact tell us that our grief and anxieties stem from the world around us and are not just makings of our own. In times of despair, we can always resort to them and find a deep sense of sisterhood in the world of our literary counterparts.

Have you ever felt that everything you’ve been working towards has been a lie? Well, our twenties are the time of constant learning and unlearning and then relearning. This is when the illusions fall off and we are left to contend with cold hard reality. Ingrid, from Elaine Hsieh Chou’s debut novel — Disorientation, is going through something similar. She is a final year PhD student, struggling with her dissertation on a Chinese American poet named Xiao-Wen Chou. Through the larger-than-life characters and humor, Chou has highlighted the exclusion, frustration, and identity crisis 29-year-old Ingrid is going through. Her fiance turns out to be a gaslighter who fetishizes Asian women and the Chinese poet she has been researching for ages turns out to be a white man in yellowface. As Ingrid navigates the perils of academia and her interpersonal relationships, readers can feel that her uncertainties and stubbornness are a direct impact of a deep sense of self-resentment.

Ingrid’s self-loathing doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The separation of the exterior self from her inner self is what many Asian Americans face considering the racism hurled at them daily. Ingrid is unaware of all the potential she carries as she has been raised in a society that benefits from her self-negation. Ingrid wrestles with estrangement from her Chinese culture. She is always gaslighting herself into believing that maybe she is meant to be satisfied with the crumbs thrown at her. Despite being smart and strong, it takes her years to see through her fiance’s emotional manipulation.

Disorientation also sheds light on the importance of female friendships. Eunice, Ingrid’s best friend, has been quite a force, pulling Ingrid out of the consequences of her actions time and again. Even though Vivian and Ingrid have their differences, they do come through for each other in times of need. As much as the outside world tries to wreck Ingrid, ultimately she revives the strength within herself that has been lying latent all along.

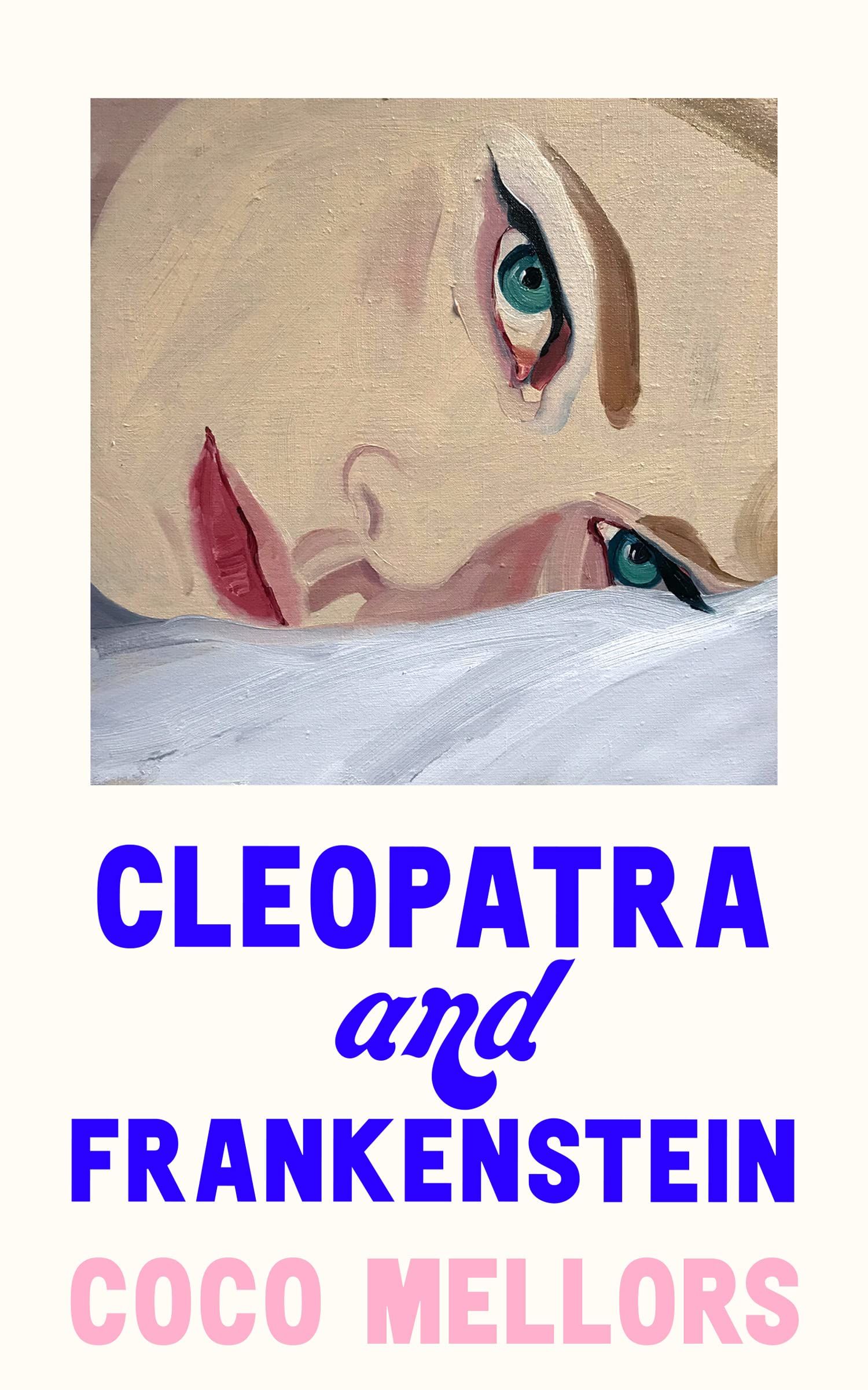

In Coco Mellors’s Cleopatra and Frankenstein, we meet beautiful twentysomething Cleo. She marries Frank, who is decades older than her, after six months of dating him. But being married to an entire person is too much for Cleo. She is all alone in the tyranny of her mind. Attraction cannot be helped, as Cleo listened to the heat of passion and plunged into a marriage that is far from ideal. Her terrible childhood and apathetic father make her life more vacant, adding to the hollowness inside her. She doesn’t have the means to heal herself just yet.

The voyage of self-discovery that Cleo embarks on brings out the greater problems of our society that are too big to be resolved by any individual overnight. The common belief that unhappiness and artistry go hand in hand is also detrimental to how we think of mental health. Frank never really judges Cleo’s skills but after they part ways there’s a moment when he thinks Cleo has certainly been unhappy enough to be a good artist. The consequences of these popular narratives are inimical, to say the least. Cleo encounters envy, goes through financial hiccups, suffers from a loss of self, uses romance as a distraction from the self, and yet keeps going.

The biggest lesson we learn from Cleo is how she is still very young and can afford to make mistakes. In a society where women are constantly vilified and monsterized for focusing on their own desires, erotic or otherwise, Cleo’s character is nothing short of rebellious. She is far from having her life together. Even though she is beautiful, Mellors hasn’t turned her into a spectacle. Just like any other woman in her twenties, Cleo is also standing in front of the abyss, waiting for it to consume her or show her the way out of it.

The plight of the twenties is always going to be there. But when it gets hard, may we always find strength in the Ingrids and the Cleos and may we always remember that “this too, shall pass.” And most importantly, may there be more books about women in their twenties as there can never be enough literature that captures the varied highs and lows of this roller coaster ride of a decade.

![Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic] Key Metrics for Social Media Marketing [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/nP1lliSbrTbUmhFV6RdAz9qJZFvsstq3IG6orLUMMls/g:ce/rs:fit:770:435/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3NvY2lhbF9tZWRpYV9yb2lfaW5vZ3JhcGhpYzIucG5n.webp)

![Twitter Shares Ads Best Practices to Help Refine Your Tweet Marketing Approach [Infographic] Twitter Shares Ads Best Practices to Help Refine Your Tweet Marketing Approach [Infographic]](https://www.socialmediatoday.com/imgproxy/OzP3VBtSIZBNMgpdhSTjIj4id8sCClj98pvK9uMLwnk/g:ce/rs:fill:770:364:0/bG9jYWw6Ly8vZGl2ZWltYWdlL3R3aXR0ZXJfYWRzX2Jlc3RfcHJhY3RpY2VzMi5wbmc.png)